Make China Great Again

China is on course to reclaim its historical position as the world’s largest economy by 2050. But the Chinese government, not satisfied with this trajectory, wants to modernize its economy and occupy the highest parts of global production chains – including pharma – much sooner. Will “Made in China 2025” succeed? We speak with industry insiders, consultants and academics to find out where The Red Dragon is headed – and what non-Chinese pharma companies need to know.

Taking a long-view of history, China’s current economic standing, relative to other countries, is an aberration. For most of recorded history, China has accounted for around 30 percent of the world population and 40 percent of world GDP. Indeed, as late as 1820, China’s share of global GDP was greater than Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and the United States combined (1).

As Henry Kissinger notes in “On China,” Western observers encountering China in the early-modern era were stunned by its material prosperity. In the 1760s, French political economist Francois Quesnay said, “[N]o one can deny this state is the most beautiful in the world, the most densely populated, and the most flourishing kingdom known ” (1). As Kissinger points out, although China traded with foreigners and occasionally adopted ideas and inventions abroad, it often believed that the most valuable intellectual achievements were to be found within its borders. They had a point. For most of history, Chinese technological achievements matched their Western European, Indian and Arab counterparts, and prior to the industrial revolution, China was for centuries the world’s most productive economy. But as Europe developed railroads, steamboats, mining and agriculture during the 18th and 19th century, China remained reluctant to embrace foreign innovations. A “Great Divergence” followed – along with a rapid decline of China’s global share of GDP.

But on its current trajectory, China will reclaim its historical position as the world’s largest economy by 2050 – accounting for around 20 percent of global GDP (2) and rivaling the combined economic might of the US and the EU27. Gone are the days when China looked upon Western technological and economic achievements with disdain. Today, the Chinese government seeks to emulate their successes – even copying foreign methods and institutions.

Trade Wars

The United States’ trade deficit with China has become a significant issue for President Trump’s Administration. In March 2018, Trump unveiled plans for a 25 percent tariff on steel imports and a 10 percent charge on aluminum. The move followed forced technology transfer and IP misappropriation claims in a “Section 301” proceeding – which, under the Trade Act of 1974, requires the United States Trade Representative to take action in response to a foreign government’s violation of a trade agreement – initiated in August 2017. “The technology transfer issue was part of the negotiation of China’s accession to the WTO in the late 1990s, and it has continued to be an issue since then,” says Abbott.

In May 2018, the trade war was put on hold while the two countries sought an agreement. According to the joint statement, “Both sides attach paramount importance to intellectual property protections, and agreed to strengthen cooperation. China will advance relevant amendments to its laws and regulations in this area, including the Patent Law.” However, in June 2018, Trump decided to push on with plans to impose tariffs. The tariffs target mainly Chinese industrial machinery, aerospace parts and communications technology; but pharmaceuticals were removed from the original tariff list.

“Current US trade policy designed to slow down China’s technological advance seems designed to reinforce the need for China to concentrate on the development of its own technology and industrial capacity,” says Abbott. “It is odd that the US administration has ‘Made in USA’ as a central policy theme, yet in the same breath it is complaining about China’s policy. How do you square that?”

Chow argues that the US might be able to effect change in China’s technology transfer regime, but he does not agree with the current approach taken by the Trump Administration. “A more effective approach is through the use of regional treaties, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership,” he says. “This has specific provisions prohibiting some of China’s technology transfer laws. But the US withdrew from the TPP…”

Made in China 2025

Made in China 2025 is the Chinese government’s plan to create a “modern,” more globally competitive economy. The idea is to transition away from “dated” industries, such as coal and steel, to make way for higher value industries, focused on science and innovation. Labor productivity is several times lower in China than in industrial countries and even some developing countries (2). Moreover, Chinese enterprises use an average of just 19 industrial robots per 10,000 industry employees, compared to 531 in South Korea, 301 in Germany and 176 in the United States (2). China seeks to change this by making use of production lines and management processes based on modern information technology and highly automated machines.

“Singapore, Japan, Korea, the US, Germany and Britain have all implemented similar strategies in the past,” says Diana Tan, General Manager of Kantar Health China, a global healthcare consulting and research firm. Miao Wei, Minister of Industry and Information technology (MITT) in the Chinese government adds, “By 2025 [...] China will basically realize industrialization nearly equal to the manufacturing abilities of Germany and Japan at their early stages of industrialization,” (3). According to Tan, Made in China is widely seen as being modelled on German Industry 4.0 and other countries’ similar plans or blueprints. It will focus on:

- improving manufacturing innovation

- integrating technology and industry

- strengthening the industrial base

- fostering Chinese brands

- enforcing green manufacturing

- promoting breakthroughs in “10 key sectors”

- advancing restructuring of the manufacturing sector

- promoting service-oriented manufacturing and manufacturing-related service industries

- internationalizing manufacturing.

“The scope and the effort put into the strategy is quite remarkable,” says Max Zenglein, researcher at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. “Although the top down industrial policy is nothing new to China, the complexity has greatly increased. To reach its targets, the government is employing a wide set of tools, including setting up massive funds and supporting the build-up of a new environment for innovation and industrial clusters. There are efforts to learn from past failed experiences and attempts to reduce inefficiencies in resources. In part, the effort also includes integrating successful private companies to complement efforts by state-owned companies.”

The state will play a significant role in Made in China 2025, providing an overall framework, as well as financial and fiscal tools, through the creation of manufacturing innovation centers (15 by 2020 and 40 by 2025). “China is and will be for the foreseeable future a state controlled economy,” says Mark Wareing, Minister-Counsellor and Director, Advanced Manufacturing, Innovation, Technology and Transport at the UK Department for International Trade. “There will be restructuring of old industries and investment in modern industrial parks with incentives offered for foreign investment, plus relaxation of company ownership laws. This is already happening, not only in the Tier 1 cities, but also in other, poorer areas. There is also the proposed Greater Bay Area initiative, which will link the areas of the Pearl River Delta with the entrepreneurial heartland of Shenzhen and the financial might and logistics portal of Hong Kong.”

One of the “10 key sectors” targeted by the Chinese government is pharma and medical devices. China currently has the second largest pharmaceutical market in world – only the US is bigger. A clear goal is to make Chinese biopharma companies more competitive, and to have Chinese firms move up the value-added chain in production.

The Chinese pharma industry has seen rapid growth over the past decade, with sales increasing from $26.2 billion in 2007 to $107.1 billion in 2015 (4) – something that Fadia Gadar, VP Global Business Development at SGS, has witnessed first-hand. “When I first visited China over a decade ago, I would never have thought things could get to where they are now,” she says. “Over the past three years, things have begun to really change. For example, just a few years ago you would barely see any foreign cars, now you see Hondas, Toyotas, and, more recently, BMWs and Mercedes. And on the business side, when you look at the qualifications of the people we hire, in terms of their knowledge and ideas – it’s very impressive.”

However, though pharmaceutical sales have rapidly increased in China, research and development remains relatively low: the ratio of R&D to sales was around 2.7 percent for most Chinese pharmaceutical companies in 2012 – significantly lower than that of US counterparts (ranging from 15–20 percent). Most Chinese firms, therefore, engage in low-value-added activities, such as manufacturing, formulating, packaging and distributing generic products. The sector also struggles with overproduction of certain drugs. For example, in 2012 there were 1272 applications of generic drugs, each of which was submitted by different sponsors more than 20 times, accounting for 60.7 percent of the total. And in 2014, the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) released the first list of overproduced drugs (more than 500): 34 categories of drugs were manufactured by more than 500 pharmaceutical companies in China, such as aspirin, ibuprofen, metronidazole and norfloxacin. Overproduction has become a serious problem for the Chinese pharmaceutical industry: manufacturers rarely exceeded a single-digit profit margin, often failing to make a profit entirely (5).

But the Chinese government is keen for things to change. One big challenge is that R&D costs money – and most generics companies in China’s fragmented market can’t afford to invest. As of 2012, there were around 4500 domestic pharmaceutical manufacturers and 14,000 domestic pharmaceutical distributors in China, and more than 70 percent of pharmaceutical manufacturers were small-scale enterprises with less than 300 employees and revenues of less than $3 million (5).

A regulatory revolution

To remedy the situation, the Chinese government will need to promote stricter standards, which should price out smaller companies, leading to consolidation and, thus, greater economies of scale – which it is doing, largely based on the US FDA model.

“They are following the FDA by the book – to show the rest of the world that they are trustworthy,” says Gadar. Carolina Ung, lecturer at the University of Macau, and co-author of a paper looking at the obstacles and opportunities in Chinese pharmaceutical innovation, cited above (5), believes that the current reform of China’s regulatory system is a multifaceted undertaking. “From the waves of new and revised policies and regulations seen in the past years to the recent major historical structural reforms of the regulatory system, it is obvious that China is aiming to improve regulation efficiency and consistency,” she says.

Frederick Abbott, Professor of International Law at Florida State University, USA, and author of a WHO report on Chinese policies to promote local production of pharmaceutical products (6), believes China is making substantial strides in improving the quality and safety of the medicines it produces. “There has been a great deal of attention on good manufacturing practices, new mechanisms for medicines approvals (including allowing transfers of marketing approvals between researcher-applicants and third-party producers), environmental controls, recognition of foreign approvals, foreign investment controls, competition law, IP, and so on.”

As Abbott’s report for the WHO shows, China’s pharmaceutical industry developed when the country was relatively isolated from international trade – and while the economy was closed, regulation was not a priority. “This left the regulatory framework with a lot of need for improvement,” says Abbott. “But a lot has already been accomplished.”

A big change came with the 2010 revised edition of Good Manufacturing Practice for Pharmaceutical Products. According to the WHO report, “It was widely anticipated that these strengthened GMP regulations would raise compliance costs to the point where smaller and less well-capitalized manufacturers would cease doing business.” In fact, Pharma China estimated that over 1000 Chinese pharmaceutical companies would be pushed out of business, while Chinese experts predicted that compliance with the 2011 standards would raise the cost of drug products by 30 percent (6).

Tan argues that regulations are rapidly evolving in other areas. “One area is Generic Consistency Evaluation (GCE), which has recently set higher standards for ingredients and manufacturing processes,” she says. “Generic drugs will need to show therapeutic equivalence in efficacy and safety to their innovator counterparts, through bioequivalence testing. Companies that comply with the new policy will benefit from a lower tax burden of 15 percent (versus 25 percent). What is essentially a quality initiative will also have an impact on affordability and lowering the cost of healthcare in China (premium pricing for off-patent drugs will be difficult to justify .”

Warning Leaders

China is in the process of overhauling its regulatory system to bring its standards closer to those in the US and Europe, but there is still a long way to go. Data published by the FDA on inspections, warning letters and red lists (import alerts) across the world gives an insight into the scale of the challenge.

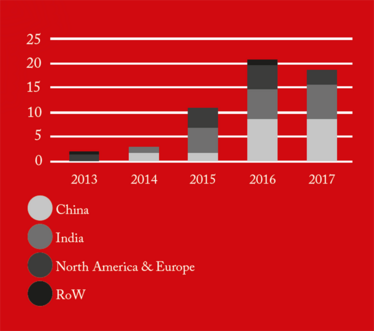

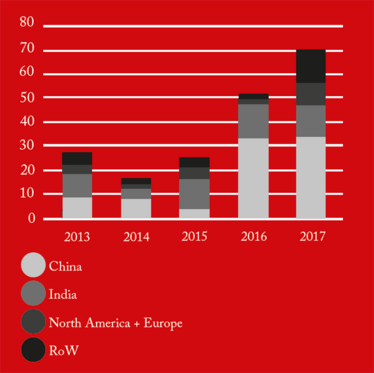

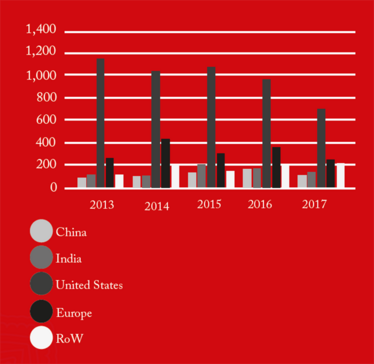

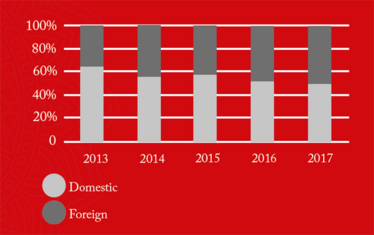

From 2016 onwards, China received the greatest number of warning letters and red lists (refusing an inspection or gross misconduct), of any country in the world (see Figure 1). This may be a reflection of the dramatic pace at which the Chinese pharmaceutical market has grown over the past five years, as well as a decline in compliance. The figures also demonstrate how globalization is forcing the FDA to spend an increasing amount of time abroad. In fact, as of 2017, the FDA is inspecting foreign and domestic drug facilities in equal number (see Figure 3).

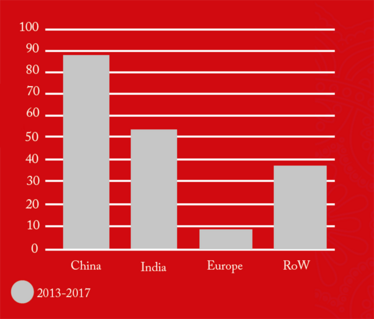

The figures also revealed that 88-100 percent of all foreign drug manufacturing sites added to the FDA red list during the five-year period (2013-2017), remained there as of June 2018 (see Figure 4). This suggests that is takes a significant amount of time and effort to “de-list” and the vast majority of firms are not managing it. Of those 191 sites still on the red list, 88 were in China and 54 in India, collectively contributing 74 percent of the total import alerts.

Overall, these findings suggest that Chinese (and Indian) pharmaceutical producers still have a long way to go, with more stringent quality controls, more rigorous monitoring and documentation needed.

Reference

1. FDA, “Import Alerts”, (2018). Available at: bit.ly/2KWowCs.

Figure 1. API cGMP Warning Letters by country/region.

Figure 2. FDA Red List by country/region.

Figure 3a. FDA GMP inspections of registered domestic and foreign drug establishment by region.

Figure 3b. FDA GMP inspections of registered domestic and foreign drug establishment by region.

Figure 4. Drug manufacturing sites added to the FDA Redlist from (2014-2017) that are still on the Redlist (as of June, 2018).

China is also making significant improvements to its regulation of clinical trials. “We see more clinical trial centers – from specific clinical sites accredited with GCP (Good Clinical Practice) to all qualified hospitals, improvement in Ethics Committee processes, a greater number of drug reviewers hired, as well as self-inspection of clinical trial data,” says Tan.

China’s decision to join the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) is another step towards higher standards as part of the country’s regulatory reforms. To join the ICH, new members must implement a basic set of regulatory requirements for the manufacture of pharmaceuticals, for the conduct of clinical trials, and for stability testing of pharmaceutical products. But many smaller companies still struggle to meet ICH standards. Abbott points out that, as with India, “There are substantial differences between the quality controls in place among the major producers with international presence and smaller producers addressing only the national/local market.”

“When you look at our client portfolio at SGS, the vast majority are local companies,” says Gadar. “We find that the regulations are still quite loose for the smaller companies, in local markets, whereas the larger firms will closely monitor quality. Once we had the FDA approval in our laboratory in Shanghai, we started to see an increase in business with the large, multi-national companies, suggesting that that for those companies, CFDA approvals are not enough to satisfy their outsourcing requirements and strategies.” (However, quality concerns are not limited to small firms selling into the domestic market, as our box, “Warning Leaders,” shows.)

China also faces the problem of competing with private industry for individuals well-trained in regulation, making it difficult to retain staff. “I would not underestimate language as a barrier to training of personnel,” says Abbott. “There are not many pharmaceutical specialists from the OECD who are fluent in Chinese and available to conduct training programs.”

A protectionist plan?

With China joining the ICH and bringing its standards in line with the rest of the world, as well as implementing policies to encourage foreign investment, some have seen Made in China as a move towards globalization. And yet, the central goal of Made in China 2025 is to occupy the highest parts of global production chains – which some commentors have described as “protectionist.” Indeed, the plan identifies the goal of raising domestic content of core components and materials to 40 percent by 2020 and 70 percent by 2025. Hitting this goal would represent a serious threat to manufacturing industries across the developed world. Max Zenglein and his team found that the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Hungary, Japan and South Korea are most vulnerable – “due to the importance of manufacturing in the targeted industries in the relevant countries,” says Zenglein. As for pharma, Zenglein’s team found that within the EU economies, the pharmaceutical sector would be the sixth most affected industry. “Based on the relevant importance of the sector in their country, Belgium, Ireland and Denmark are potentially most at risk,” he says.

That said, Zenglein believes China offers significant opportunities for foreign companies – at least for now. “China is still in dire need of key technology, which provides great opportunities for foreign companies,” he says. “But companies will also need to be aware that China is changing as an economic partner. It is a market with great potential but also one in which the government is heavily supporting Chinese companies. One of the aims of Made in China 2025 is to increase the market share of Chinese companies in the targeted sectors not only within China but globally. Companies will need to balance their short-term business interests with the long-term risks.”

Jin Zhang, pharmaceutical business strategist and the editor of The Pharmaceutical Consultant offers some advice for foreign companies looking to invest in China. “First, you must recognize that the product is very important – focus on companies with innovative products,” she says. “Second, look for a team with experience in the Chinese market. Third, recognize that the Chinese market has different needs from other countries. And fourth, play by China’s rules – what works in the US and the EU might not work in China.”

Foreign companies in China must also deal with further so-called protectionist practices around intellectual property enforcement. Daniel Chow, Ohio State University College of Law, wrote a paper on the three major problems threatening multinational pharma companies in China (7). “I first encountered the problems working for Procter & Gamble in China,” he says. “I was in charge of protecting P&G’s brands and discovered that there was a major counterfeiting problem with various products, including pharmaceuticals.” Chow argues that competition law authorities use heavy-handed tactics, such as dawn raids to intimidate multinational companies (MNCs) in China. “PRC authorities also charge MNCs with price fixing, use aggressive tactics to pressure MNCs to lower their prices, and also accuse MNCs of engaging in bribery of PRC officials to obtain business,” says Chow. “Chinese companies that engage in far more egregious practices often have not been prosecuted.”

Chow also argues that China has a web of policies that force companies to transfer their pharmaceutical patents to Chinese companies. “The lower level of protection in China means that patent rights become available to the public more rapidly than in the US or EU,” he says. “For example, pharmaceutical companies will first apply for a patent before they seek regulatory approval in China for the drug. The US and EU provide a period of marketing exclusivity for the drug after the end of the patent to compensate for the loss of the patent term during the approval process. China does not, effectively reducing the life of the patent by 40 percent.”

MNCs have also complained for years about forced technology transfers in exchange for market access in China. Gadar believes that foreign companies can’t do much about this problem. “The issue is always the same – it’s trust,” she says. “There may be things you can do, but at the end of the day, you’re dealing with humans. The most important – and difficult – thing is to find people you can trust.”

Mark Wareing believes there is a need in China to standardize enforcement and raise penalties for IP infringement. “Otherwise, the desire to innovate (and hence develop IP) will not be achieved,” he says. “But you can expect to see loosening of ownership structures (already announced by President Xi) and tightening of IP laws – in fact, over 95 percent of IP cases in the courts are now Chinese on Chinese. Also, several of the New Technology Parks and Zones specifically reference local support for IP enforcement to assuage foreign fears.” Wareing believes foreign investors must pick their locations and their partner organizations carefully and take good, impartial, local advice. “Embassies are particularly supportive here,” he says.

Abbott also believes that China has undergone a transition in the field of IP protection. “On their face, China’s IP laws are consistent with the TRIPS Agreement, and the Chinese government has been encouraging domestic filing of patent applications, and the rate of patenting in China is increasingly comparable with major OECD countries,” he says. “Countries in the process of development go through a transition between predominance of appropriation and innovation. Enforcement is likely to be weak during the appropriation/catch-up phase and to grow stronger as the country becomes an innovator. Enforcement of IP in China has improved substantially in recent years. As the Chinese government is now focused on biopharma innovation, patent enforcement is likely to be a more substantial priority. Paradoxically, I expect that, within the next decade, OECD industry will be as or more concerned by Chinese over-enforcement of IP rights than under-enforcement.”

Chow disagrees. “My own view is that China under Xi Jinping is moving in the opposite direction and will become even more protectionist and nationalistic in the near future without effective intervention by the US and possibly other allies,” he says. “The US government might be able to change this course – and I know that the Trump Administration is trying to do so with aggressive trade practices, such as increased tariffs, directed against China. But this is a dangerous, risky tactic that might backfire. It remains to be seen what will happen.”

Vendor’s View

Qing Li is General Manager of Life Sciences, GE Healthcare, Greater China

Can you give me an overview of your activities in China?

We are the largest medical equipment manufacturer in China and operate five global manufacturing sites in the country. GE Healthcare China operates multiple entities with more than 7,000 employees, including an R&D team of over 1,000 engineers.

The first KUBio, GE’s modular, prefabricated biomanufacturing facility for monoclonial antibodies (mAbs), was opened for JHL Biotech in China in 2016. Also, the first FlexFactory for cell therapy, a semi-automated end-to-end manufacturing platform is being delivered to China for Xiangxue Pharmaceutical. The FlexFactory will help the company to scale up, digitize and accelerate manufacturing processes for their cell therapy clinical trials, supporting future commercialization.

What are some of the main trends you see in the Chinese life sciences and healthcare industry?

Both the life sciences and healthcare industry as a whole in China are growing fast and are expected to maintain the upward trend in the coming years. And within life sciences specifically, I see a strong growth in the mAb and cell therapy spaces. There are currently 268 molecules in clinical trials, from 139 Chinese companies, with 11 already approved (according to our internal analysis). I personally predict there will be at least 20 mAbs approved for commercial production in the next five years. The number of mAbs (mostly biosimilars) being developed in China has outpaced the rest of the world. And the speed at which companies are now moving from initial development to novel therapies launching in the market is also phenomenal – driven by central government support, sufficient funding, CFDA policy reform, and wide adoption of single-use technologies.

The cell therapy area, especially CAR-T, is growing quickly in China after the FDA approvals from Kite and Juno in 2017. Since the CFDA released new guidelines last December, there are over 20 CAR-T Investigational New Drug Applications, with more coming soon. For cell therapy development, China has become the second largest globally with 203 projects in the pipeline.

How do you think Made in China 2025 will impact foreign companies that invest in China?

Made in China 2025 is designed to transform China into a world manufacturing power. And it brings both challenges and opportunities for foreign companies investing in China. We will see more favorable policy measures to support domestic industry growth, which means foreign companies will face tremendous competition with local companies. But there are also opportunities for growth as well. Foreign companies should think more and do more for the domestic market in China, for reasons of cost, ease of doing business and agility of response. We have laid out our In-China-for-China strategy to resolve Chinese customer pain points, and work closely with customers.

We opened our China FastTrak innovation and training center back in 2006, which has trained thousands of engineers working in the biopharma industry and developed/optimized dozens of bioprocesses for mAbs, vaccines and plasma applications. We also collaborate with Wego Group (China’s largest medical device consumable company) to produce single-use consumables, to combine local innovation and manufacturing strengths to enable the realization of biologics “Made in China 2025.”

How do you see the Chinese pharmaceutical market developing over the next decade?

The next 10 years should be a golden age for the Chinese pharmaceutical market, especially in the biologics and the cell and gene therapy fields. With strong investment, the regulatory process bottleneck is expected to fade and private insurance companies are emerging to pay for expensive biologics – entrepreneurship in China is poised to become wildly successful. This, in turn, could trigger even more excitement for the biologics industry. It is not surprising that IMS Health predicts that China could be the world’s second-largest biologics market by 2020.

Reference

J Tang et al., “The global landscape of cancer cell therapy,” Nat Rev Drug Disc, 17, 465-466 (2018). PMID: 29795477.

Will China dominate?

The world has already seen how the US and the EU – because of their large markets and preference for strict consumer and environmental regulations – have effectively been able to export their regulatory standards to the rest of the world. Could China replace the EU and the US as a source of de facto global standards? The answer will hinge upon the success or failure of China’s ambitious plans to create globally dominant hi-tech industries, such as pharma, as the country attempts to reclaim its historical position as the world’s largest economy.

“There are around 100,000 State Owned Enterprises of some form or another and China has massive resources, particularly in finance,” says Wareing. “If it is the intention to achieve the ambitions of Made in China 2025, then it will be done.”

Zenglein isn’t so sure. “China certainly is an economic force to reckon with and is quickly emerging as an increasingly competitive and capable global player in more sophisticated industries,” he says. “But it is doubtful that all of the targets will be reached within the set timeframe by 2049.”

“China is providing incentives for talented expatriates to return to China to pursue research,” says Abbott. “It is training large numbers of PhD scientists; it is providing R&D subsidies, including R&D parks; it is making it easier to move products from laboratory to marketing authorization and production; it has improved its patent system; it is encouraging foreign investment in R&D centers. China appears quite serious about becoming one of the major biologicals R&D and production centers.”

The Chinese market will maintain its strong growth in the next decade, according to Zhang. “The majority of Chinese pharmas will focus on improving the quality of generic drugs and expand their territories in China,” he says. “However, some leading pharmas will definitely begin to enter overseas markets and begin to play a more important role in the global stage.”

So far, China’s regulatory capacity and the willingness to elevate the protection of consumers and the environment has not kept pace with its economic growth. And as Anu Bradford argues in her paper on the “Brussels Effect,” though China may soon be the largest consumer market, GDP per capita is a better prediction of a country’s regulatory propensity (8). “I think it’s a culture – mindset – thing,” says Gadar. “Many in China have now been exposed to the Western world but many are still driven by the local. I think, in time, China will move towards a compliance culture.”

Gadar also points out that China is only one of the world’s rapidly developing economies. “Malaysia, Indonesia, India – the whole East Asia Pacific region is growing,” she says. China may well create a globally competitive pharma industry in the coming decades, but several other countries will not be far behind.

- H Kissinger et al., “The singularity of China”, On China, 6–33. Penguin Group: 2012.

- Pwc, “The Long View”, (2018). Available at: pwc.to/2kl6hcQ. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- China Daily, “’Made in China 2025’ plan unveiled”, (2015). Available at: bit.ly/2vHIjOQ. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Deloitte, “The next pharma: Opportunities in China’s pharmaceuticals market”, (2015). Available at: bit.ly/2IBvtD4. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- J Ni et al., “Obstacles and opportunities in Chinese pharmaceutical innovation”, (2017). Available at: bit.ly/2qa6lxn. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- FM Abbott, “China Policies to Promote Local Production of Pharmaceutical Products and Protect Public Health,” (2017). Available at: bit.ly/2MyPLiS. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- DCK Chow, “Three Major Problems Threatening Multi-National Pharmaceutical Companies Doing Business in China,” (2017). Available at: bit.ly/2IC2rTH. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- A Bradford, “The Brussels Effect,” (2012). Available at: bit.ly/2KzSzeT. Accessed June 29, 2018.

Over the course of my Biomedical Sciences degree it dawned on me that my goal of becoming a scientist didn’t quite mesh with my lack of affinity for lab work. Thinking on my decision to pursue biology rather than English at age 15 – despite an aptitude for the latter – I realized that science writing was a way to combine what I loved with what I was good at.

From there I set out to gather as much freelancing experience as I could, spending 2 years developing scientific content for International Innovation, before completing an MSc in Science Communication. After gaining invaluable experience in supporting the communications efforts of CERN and IN-PART, I joined Texere – where I am focused on producing consistently engaging, cutting-edge and innovative content for our specialist audiences around the world.