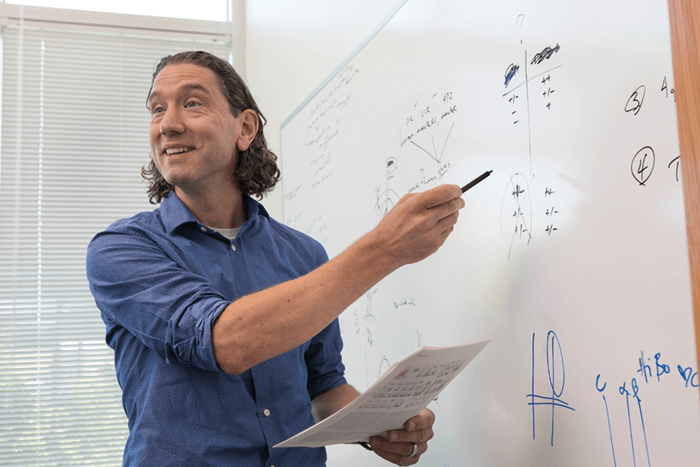

How is the immuno-oncology field changing – and what new research is emerging?

It’s not even been ten years since the first approvals emerged for immuno-oncology drugs, but the impact has been remarkable. Over the next ten years, the industry will uncover new research and hopefully increase the number of patients that are able to respond to treatment. Right now, there is a lot of fascinating science emerging from microbiome research, both in academia and industry. This is an area that has largely been untapped for oncology, but our understanding has expanded significantly over the last few years. In a short space of time, we’ve learned not only how the microbiome affects the immune system with regards to cancer, but also how it can have a potent effect on other aspects of health. I am really interested in how the microbiome interacts and enhances immune responses. There is likely scope to better understand an individual’s microbiome and take advantage of its interaction with the immune system; indeed, BMS is driving some excellent collaborations in this area, with a view to enhancing immune response to cancer. Another emerging area that has large potential is increasing our understanding of how innate immunity affects anticancer responses. New research is looking at turning on the immune system in places where it is not very active, or enhancing it where it’s suboptimal for anticancer therapy.When developing these therapies, what are the challenges with side effects?

There can be side effects if the immune system is hyper activated – this is something we look at very carefully. There are many really smart people dedicated to understanding how the immune system responds, as well as the similarities between autoimmune disease and immuno-oncology (although obviously they are going in two different directions). There are important, and sometimes subtle, nuances and differences between those effects, and turning off one pathway in autoimmunity is not equivalent to turning it on for cancer therapy. At BMS, we spend a great deal of time trying to understand how things differ and how we can walk the line of activating what we want to and where we want, without triggering an overactive response elsewhere. We also put a lot of effort into identifying targets that are as tumor-specific as possible. We are now seeing fantastic scientific data and clinical success, but certainly not every patient or cancer type is responsive. It will be a significant challenge to reach the point where we really understand – on a molecular and cellular level – what is happening within an individual patient’s tumor; how is the tumor avoiding destruction by the immune system? Why does the tumor continue to grow in the face of what should be a fairly effective response? Picking apart tumor resistance mechanisms will allow us to combine the right approaches to get the best possible responses in each patient.You studied English literature and biology; why combine the two?

Some have told me that it seems an unusual combination, but it made sense to me. I’d always had an interest in literature, but I had an aptitude for science. The decision turned out to be a very good one because the ability to use language and communicate effectively is incredibly important in science. These skills can often be overlooked and don’t always come naturally to scientists. Combining science and English means that I can think and write in different ways – analytically and in terms of language. Being able to communicate well is a crucial foundation for effective collaboration. The first professor I ever had for immunology once told my class that immunology is, in many ways, a language first; before you can move on and grasp the most complex ideas and concepts, you have to be able to work within the language of immunology. She was right – it really is a separate language, with different types of cells, different processes, and other aspects that accumulate to build the immune system. Throughout my career, whether mentoring or working with collaborators, I’ve found that it is important to use common but engaging language.How did you get started in industry?

Following graduation from Rutgers University, I stayed on at a laboratory where I’d worked as an undergraduate, which gave me an opportunity to really build a foundation for research. I did a lot of work with basic immunology and I was also given the opportunity to lead work and have projects of my own, which isn’t very common for a new graduate! I went on to do a PhD in immunology in Chicago and then moved on to a cancer biology laboratory in Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania. In time, I had the opportunity to apply to the oncology department at BMS. I was really keen to move into industry to get involved with real drug development and I was so impressed by the oncologists there during the interview. I worked for a number of years in BMS’s oncology group in Princeton, New Jersey. As the years went on, immuno-oncology really started to arise as an exciting new way to treat cancer. We had some collaborations in place at the time, but the field was so new that most companies didn’t have specialized immuno-oncology departments. BMS eventually acquired Medarex, led by Nils Lonberg and Alan Korman, pioneers in immuno-oncology research. I worked very closely with them and then after six years in Princeton, I moved to Northern California where the immuno-oncology group was centered. I’ve worked here ever since. Immuno-oncology was a really good fit with my background, having done research both in immunology and cancer biology. Working with Nils and Alan was an absolutely incredible opportunity. These two scientists were very senior people within the organization, but they really understood – in extraordinary detail – the fundamental science that leads to complex immune interactions and responses. It really encouraged and energized me to spend a lot of time working on more effectively understanding the biology behind what we work on. And it was wonderful to see that such senior members of an organization can still be very tapped into science and research. Alan and Nils’ extreme perseverance and persistence in following good science was another valuable and broadly applicable lesson. Science can be a very frustrating field at times and you need to work to have your ideas accepted. They talked about the history of the field and how, not even ten years ago, many experts believed that immunotherapy would never be effective. Today, we know that it holds significant potential.