Are You REACH Ready?

The final deadline for the European Union’s REACH regulation is approaching – and the home stretch will be the most challenging, especially for pharma companies that have failed to recognize their role.

In 2006, the European Union introduced a regulation concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (called REACH) (1). One of the main aims is to better protect both human and environmental health from the dangers posed by chemical substances – quite a broad statement, so allow me to clarify. In 2005, a study conducted by the UK’s University of Sheffield, on behalf of the European Trade Union Confederation, concluded that as many as 90,000 cases of chemical-related occupational respiratory and skin diseases could be prevented each year, leading to healthcare and productivity cost savings in the region of 3.5 billion Euros over ten years for EU member states (2). The study only considered non-malignant skin diseases (i.e., dermatitis), asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), so there could be many more injuries caused by chemicals every year. REACH aims to reduce the risks associated with chemicals by focusing on four processes: chemical registration, evaluation, authorization and restriction. Over the years, a huge number of chemicals have reached the European market (sometimes in very large amounts), but in many cases there is little information on the hazards they pose to human health and the environment. REACH is an attempt to fill in information gaps and to better understand and control the risks.

Some key aspects:

- Manufacturers and importers must gather information on the properties of chemical substances.

- The European Chemicals Agency in Helsinki will manage a database and co-ordinate evaluation of chemicals of concern.

- Some very high hazard chemicals will be substituted with suitable alternatives that have been identified.

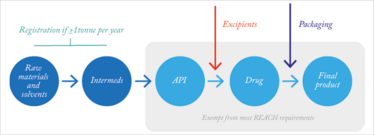

Figure 1. How REACH affects pharmaceutical production.

Registration ready

Over the years, many companies have been confused by REACH and what they need to do – and not everyone has been prepared for the paperwork. REACH affects any industry that uses chemicals, though some exemptions do exist – for example, substances used in human and veterinary medicines. Importantly however, this does not make the pharma industry completely immune to the regulation. What about process chemicals, including reaction-supporting agents and solvents, such as DMAC (N,N-dimethylacetamide), and the intermediates used to make APIs? For the vast majority of chemical and downstream supply chains, someone will need to register substances with the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). And the question is who? Is it the chemicals company? Or the pharmaceutical company? Well, it depends on the structure of your supply chain. If it’s an EU-based pharmaceutical company importing chemicals from an EU-based chemical company, then it will be the chemical company who does the registration. But if an EU pharmaceutical company is importing chemicals from outside of the EU, such as the US, then the onus is on the pharma company to REACH register the chemicals.

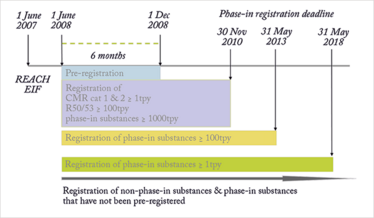

Registration is the most cross-cutting, far-reaching aspect of REACH. It’s a duty that affects any EU legal entity that manufactures or imports substances in quantities of one tonne or more per year, as well as appointed ‘Only Representatives’ working on behalf of non-EU producers. When the White Paper was published, it was estimated that tens of thousands of substances would need to be registered. To give industry a fighting chance of meeting this obligation, the regulators phased in the registration duty using a risk-based approach, focusing first on high-tonnage and high-hazard substances, moving progressively downwards in tonnage band to a final deadline on May 31, 2018.

As Figure 2 shows, most of the deadlines have passed. In the early years, there was much discussion about REACH, but now it has become a way of life for large chemical companies. However, the 2018 registration deadline will perhaps be the biggest challenge because it applies to low-volume manufacture and import in the 1-10 and 10-100 tonnes per year bands. In other words, it’s expected to involve large numbers of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). Some will only have a few substances to register, but others will have wide-ranging portfolios of low-volume substances, particularly in the specialty and custom chemicals sectors.

It is still difficult to predict the numbers of registrations and unique substances that will go through the 2018 deadline. However, recent ECHA estimates suggest that up to 70,000 dossiers will be submitted, covering somewhere between 25,000 and 50,000 unique substances – that’s more than three times the amount received for the 2010 deadline, and almost 20,000 more than the number of dossiers used to populate the ECHA database to date.

Figure 2. Registration timelines for REACH.

To register or not to register

EU chemical manufacturers and importers who fall into the above band should be thinking about registration now by addressing two key questions: “what will it cost to register this substance?” and “what is this substance worth to my business?” Where the payback period would be lengthy, either as a result of initial registration fees and data access costs or subsequent dossier maintenance costs, EU chemical manufacturers and importers might, quite understandably, choose to register only their most profitable substances. Some potential registrants in this situation may decide to cease manufacture or import entirely, or to cap their annual tonnages to avoid registration.

For the pharma companies that import chemicals from outside of the EU, the above are questions that you will need to ask. For those who import chemicals from within the EU, the situation is a little different – and could have some serious consequences. For example, post-2018, you may need to buy low-cost raw materials or process chemicals from more than one supplier. Or find a new supplier entirely. You’ll need to be in close contact with your chemical supplier to ensure that the chemicals you use will be registered.

However, the trade-off is the potential cost of implementing SCC; companies may need to invest in more onerous forms of engineering control, such as mechanical or air dynamic barriers. The need for rigorous containment also applies to the whole life cycle of the intermediate, which includes manufacture, purification, sampling, analysis, cleaning, maintenance… the list goes on. Thinking in particular about wastewater, registrants are expected to have an on-site wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) where chemical (oxidation) and, ideally, biological treatments are applied. The effluent from this plant must be monitored for residual concentrations of the intermediate. For some countries this could be an issue; for example, manufacturing sites with WWTP in the UK do not normally have biological treatment options. But even if a company does have state-of-the-art facilities, maintaining – and demonstrating – rigorous containment can be extremely demanding. In some cases, full registration may be seen as the easier option.

Learning to live without

The authorization aspect of REACH prohibits the EU use and supply for EU use of substances listed in Annex XIV to the regulation. Each substance listed in the annex has a transitional period for its phase-out; after which companies must have permission from the European Commission to continue to use that substance, unless an exemption applies.

Fortunately, there are more types of exemption from authorization than from registration, in particular for intermediates (which don’t even have to be under SCC!) and substances used in mixtures below the relevant threshold of concern. But that’s where the good news stops. Unlike registration, there is no tonnage threshold, meaning that even very small quantities of substances in Annex XIV may require authorization unless an exemption applies.

Several process chemicals – particularly aprotic solvents – are listed in Annex XIV, including 1,2-Dichloroethane (EDC), which is used extensively in drug production. The latest application date for EDC is May 22, 2016 (with an additional 18 months to its sunset date). In some sectors the remaining transitional time may be plenty to change to an alternative, but given that the pharma industry is heavily regulated in other ways, substitution cannot be taken lightly. Another potential concern is the solvent DMAC. In early 2013, ECHA recommended that DMAC be listed in Annex XIV. However, due to similarities in intrinsic properties, and interchangeability in common uses, the DMAC decision was postponed pending the outcome of an Annex XVII restriction process on n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). It was reasoned that, under the idea of regulatory coherence, any process used to control NMP should also apply to DMAC.

Even for substances not listed in Annex XVII, there could still be trouble ahead. Under the ECHA’s SVHC Roadmap to 2020 Implementation Plan (3), the authorities are encouraged to use the most appropriate regulatory mechanisms and tools to manage the risks from chemicals. ECHA and member state authorities have developed a screening method to help them identify substances with particular hazard, exposure and risk profiles – which will then be addressed using the most appropriate regulatory tools. As a result of this year’s mass screening, some 200 substances, registered by around 800 companies, were selected for manual review.

Where screening indicates a potential concern, and where there is sufficient information to substantiate that concern, voluntary Risk Management Option Analysis (RMOA) is carried out by ECHA or member states to determine whether they should propose more controls. In some cases, no further action may be required and, even if it is, other regulatory mechanisms exist that can also control risks from chemicals of concern on an EU-wide basis, for example harmonized classification and labeling, and exposure limits for the workplace.

A long-standing yet active debate is whether substances with community-wide occupational exposure limits (IOELVs) should benefit from an exemption from authorization for the uses covered by those limits. Decisions on the inclusion in Annex XIV of other previously recommended aprotic solvents, such as N,N-dimethylformamide (which has an IOELV), are currently on hold – with Italy recently notifying its intention to propose a restriction on the manufacture and industrial use of this substance. If the case can be argued successfully that to subject such substances and uses to authorization is disproportionate to the risk, and that the workplace risks are already sufficiently and properly controlled, we may see a paradigm shift. Inclusion of chemicals of concern in the authorization process could become the exception, not the norm…

But whatever may happen, REACH is not just a matter for chemical companies. Perhaps one of the main difficulties for pharma companies (among other industries) has been how to interpret the legislation. Another difficulty is how exactly you get ready for REACH – who in your supply chain is responsible for registration? The final deadline is close at hand and nobody wants to fall on the final step. Make sure you are prepared and understand the potential consequences.

Lisa Allen is a manager at REACHReady (UK).

- European Chemicals Agency, REACH Legislation. echa.europa.eu

- Simon Pickvance et al., “The Impact of REACH on Occupational Health with a Focus on Skin and Respiratory Diseases,” European Trade Union Institute Report (2005).

- European Chemicals Agency, SVHC Roadmap to 2020 Implementation Plan (2013). echa.europa.eu