Just Can’t Get the Staff!

Or can you…? The second article in our Biopharma Trends series explores staff development in the industry: which positions are hardest to fill? What skills are most in demand? And what can companies do to ensure they discover and nurture talent?

With many of the first generation of bioproduction staff reaching retirement age, along with an increasing number of biomanufacturing facilities coming on line, finding the right staff can be a real challenge for the biopharma sector. But help is at hand. In the second article of our Biopharma Trends series (see sidebar), we explore what a recent survey conducted by The Medicine Maker and Ireland’s National Institute for Bioprocessing Research and Training (NIBRT) reveals about staff development in the biopharma sector (1).

Here, we will reveal respondents’ thoughts on which positions are difficult to fill and why, what skills companies are looking for, and how can we best equip the biopharma professions of the future. To analyze the results, we’ve enlisted the help of our survey collaborators, Ireland’s National Institute for Bioprocessing Research and Training (NIBRT) – and their Director of Projects, Killian O’Driscoll – as well as experts from Thomas Jefferson University (Ron Kander and Kathleen Gallagher), and the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE; Jeffery Odum and Andre Walker).

Biopharma Trends Trio

In December last year, The Medicine Maker teamed up with NIBRT to find out about current trends in the biopharma industry. We asked 210 biopharma professionals from across the world a series of questions covering: product pipelines, manufacturing practices, staff development, opportunities and challenges within the sector. Fifty-seven percent of the respondents worked in biopharma manufacturing, 13 percent as contract service providers and 13 percent in companies that were suppliers/vendors to biopharma companies. The remaining 17 percent were affiliated with academic institutions, government organizations, or consulting.

The first article in the series looked at biopharma therapeutics, now and in the future (read more). Respondents rated mAbs as the most commercially important biotherapeutic right now, but saw cell and gene therapies as being very promising for the future. We also spoke to four Power Listers about their thoughts on the survey results and their advice on what biopharma needs to focus on to rise to the challenges that lay ahead for the field.

The third and final article in this Biopharma Trends series will consider the future of the biopharmaceutical manufacturing and gather opinions on Industry 4.0 – the fourth industrial revolution.

Bioprocess engineers in demand

The results of our survey showed that a majority (86 percent) of survey respondents had difficulty filling one or more biopharma positions (Figure 1). Bioprocess engineers were the most difficult position to fill (52 percent), followed by manufacturing science and technology staff (39 percent), upstream processing staff (33 percent), and downstream processing staff (28 percent).

“This largely aligns with our experience,” says O’Driscoll. “In particular, what we see is a shortage of what you might call engineers with ‘specialist skills’ – not just bioprocess engineers, but automation engineers, commissioning, qualification and validation engineers, and so on. It’s really a question of supply and demand.” O’Driscoll argues that the biopharma industry is growing rapidly and that such roles are in especially high demand for start-up organizations. “It takes four to five years to train a bioprocess engineer, with perhaps some post-graduate study, and ideally a few years’ experience as well,” he says.

Ron Kander, PhD, (Dean, Kanbar College of Design, Engineering & Commerce, and Associate Provost for Applied Research) and Kathleen Gallagher (University Executive Vice Present and Chief Operating Officer), both from Thomas Jefferson University, concur. “Bioprocess engineers and biomanufacturing specialists are in short supply because there are very few facilities like the Jefferson Institute for Bioprocessing (JIB) and NIBRT that combine hands-on training on industry-scale equipment with an industry-validated curriculum,” says Kander.

Jefferson Institute for Bioprocessing was the first major program to emerge from the merger between Thomas Jefferson University and Philadelphia University. Jefferson partnered with NIBRT to deliver NIBRT’s curriculum to its students – you can read more about it here. “When we speak with industry professionals, they tend to cite a lack of trained professionals in bioprocess-related support roles – including supply chain, regulation, purchasing and sales/marketing – who understand and appreciate bioprocessing unit operations,” says Gallagher.

Jeffery Odum, Global Technology Partner in Strategic Manufacturing at NNE and Teaching Fellow at North Carolina State University’s BTEC, and ISPE member, offers that universities contribute to the shortage of process engineers. “Most university programs do not teach or promote the discipline focused in the life science in a way that attracts students,” he says. “Another problem is that other industries are recruiting from the same talent pool – and they often offer higher starting salaries.” Odum also says that project managers with experience in GMP-focused project execution are also difficult to hire and retain.

Are there any differences between the US and EU market with regard to difficulties filling different positions? Kander and Gallagher believe the two markets are essentially the same. “Most large multinational corporations and small toll manufacturers are working in a global marketplace,” Kander notes. “This is one reason we are partnering with NIBRT – so someone trained at JIB or NIBRT will have equivalent experiences and will also allow workers to move seamlessly between positions in North American and Europe, making them more valuable to their employers.”

O’Driscoll agrees that there are similarities between the two markets, given that there are global trends in play. But he does see some potential differences emerging, with US companies perhaps more focused on discovery. “As we look at the newer modalities – cell and gene therapies, for example – coming through,” he says, “we may see an emerging lack of skills there, particularly in the US marketplace because of their strong emphasis on discovery.”

Odum believes the EU has done a better job promoting this GMP-focused industry as a whole, “this has generated more interest,” he says. “In the US, there are too many competing opportunities for the skill sets identified.”

Figure 1. Which of the following types of staff were respondents having the most difficulty hiring? (Survey respondents were allowed to choose more than one response to this question; hence why the responses total more than 100 percent.)

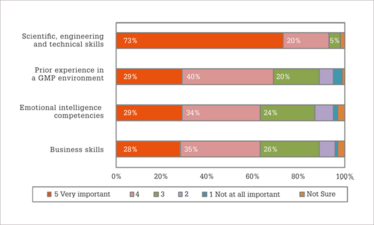

Figure 2. With regard to hiring new staff, how important is each of the following skill sets?

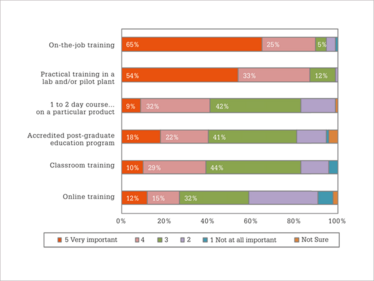

Figure 3. How effective are various types of training? (Using a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being not at all effective, and 5 being very effective.)

Can’t beat technical skills

In addition to the most difficult positions to fill, we also asked respondents to rank the importance of different skill sets (Figure 2). The most important skill set for new hires was scientific, engineering, and technical skills (rated as 4 or 5 by 93 percent of survey respondents). Whereas the remaining skill sets were each considered quite important by 63 percent to 69 percent of the respondents. The results also indicated that individuals in small companies were more likely to consider scientific, engineering and technical skills; prior experience in a GMP environment; and emotional intelligence competencies as being quite important, while those working in large companies were more likely to consider business skills, such as communication or team work to be quite important.

“Of course practical skills are vital for a career in the biopharma industry,” says O’Driscoll. “But we’ve seen a change over the past five-or-so years. Previously, when companies were hiring, they were looking for a very specific skillset for particular roles. What we’re now seeing is that as skills evolve and change and new types of roles emerge, the attitude of the person you’re hiring is fundamental.”

O’Driscoll also points out that EU GMP Guidelines (annex 1) talks about the importance of skills training and attitudes (2). “What a lot of companies are realizing is that you can hire for attitudes and then train for skills. Hiring managers will ask: can they work in teams, problem solve, conform to advanced manufacturing regulatory requirements, and learn on an ongoing basis – with a fundamental focus on quality and the patient?” He believes that the perfect hire will be someone with those softer skills and the scientific, engineering, and technical skills. “Clearly that would be the ideal situation, but those people are in short supply. Companies will therefore take into consideration attitudes and realize that people can acquire skills through continual professional development,” explains O’Driscoll.

How to find the right people

Andre Walker: Leverage networks by incentivizing existing employees to bring in known acquaintances, and then regularly publicize specific job openings to staff so they are prompted to consider their network against the opportunity. Promote from within and fill the bottom with recent graduates who are supported by well-designed training and mentoring programs.

Killian O’Driscoll: We see companies succeeding when they adopt a multi-faceted approach – underpinned by developing a strong brand, based around their employee culture. We see some startups having great success, sometimes recruiting up to 400 positions for new manufacturing facilities, when they do this. As well as using the traditional route of hiring, consider engaging with local schools, offering internships to university students, engaging at the apprentice level, and cross-skilling existing staff – perhaps from other disciplines such as small molecule manufacturing. Companies must also support continuous professional development and lifelong learning for those hired.

Jeffery Odum: Seek to collaborate with an institution that is open to innovative partnerships. These types of models have proven very successful at the community college level.

Ron Kander and Kathleen Gallagher: It is cheaper to grow talent internally and train existing employees than it is to recruit people away from your competition. Companies want to partner with the Jefferson Institute for Bioprocessing (JIB) to co-develop internal training programs for existing employees, and are also interested in identifying talent early in the academic process to “lock in” future employees by offering named scholarships, internships and graduate fellowships to students in our undergraduate and graduate Bioprocess Engineering programs. Companies are also working with our regional community colleges to identify high-quality technicians they can hire and then complete a bachelor’s or master’s degrees in the JIB facility while they are working. All these strategies are centered on identifying, retaining and growing talent from within the organization.

Andre Walker, consultant and ISPE member, says the kinds of skills required depends on the position. “If you are hiring for a technical position then scientific, engineering, and technical are very important skills,” he says. “But in my experience, biopharma companies, easily attract the most technically qualified candidates, so the key skills that result in a job offer are soft skills such as leadership, communication, and teamwork.”

Odum agrees, adding, “It’s amazing to see how the art of communication is being lost in the age of Facebook and instant messenger.”

Kander and Gallagher, however, say that employers are more interested in hands-on, practical training with real equipment. “This can range from in-depth technical training for technicians and engineers who are running bioprocessing facilities to hands-on technical awareness training for people in support roles such as sales, marketing, purchasing, legal and supply chain,” says Kander. “Employees in the biopharma industry must understand the science and engineering behind the bioprocessing unit operations and also understand in detail the operation of each step in the process.

“Another key skillset is the overall operation planning and control functions needed to successfully operate an integrated biomanufacturing process,” Kander adds. “Finally, one must understand how the biomanufacturing process interfaces with the rest of the business operation, including R&D, sales, purchasing, supply chain, regulation and legal.”

On-the-job does the trick

Respondents were also asked to rate the effectiveness of various types of training (Figure 3). On-the-job training came out on top (rated as 4 or 5, with 5 being “very effective”) by 90 percent of survey respondents), closely followed by practical training in a pilot lab and/or pilot plant environment (87 percent). Several other types of training were considered less effective: a one- or two-day course from a third-party provider on a particular topic (41 percent), an accredited post-graduate education program from a higher level education institute; for example, a Master’s in science program (40 percent), or classroom training (39 percent). The least effective type of training was online training, which was rated as quite effective by only 27 percent of the respondents; though individuals located in Asia were more likely to consider online training to be quite effective, compared to those in Europe or North America.

To Walker, these findings make sense. “Correct GMP behavior comes mostly from modeling other’s actions in everyday work and interacting with specific quality systems that are similar but not identical to other organizations,” he says. “For operational roles (operator, warehouse, etc.), SOP’s codify the actions required, but are rarely useful as day-to-day instructions. After classroom training on the requirements correct performance is achieved through documented practice and repetition with appropriate oversight.” For engineering and technical support roles, Walker believes general knowledge from university studies and the review of specific corporate procedures provide explicit (well documented) knowledge of a field, “but this is only the foundation upon which tacit (tribal, experiential, practical) knowledge is gained,” he says.

“On-the-job and practical training is more effective because of the hands-on, experiential aspect of these pedagogies,” say Kander and Gallagher. “This approach ensures that students and industry trainees will be able to retain the complex information associated with bioprocessing unit operations. There is no substitute for training on real bioprocessing equipment.”

Biopharma Trends Trio

In December last year, The Medicine Maker teamed up with NIBRT to find out about current trends in the biopharma industry. We asked 210 biopharma professionals from across the world a series of questions covering: product pipelines, manufacturing practices, staff development, opportunities and challenges within the sector. Fifty-seven percent of the respondents worked in biopharma manufacturing, 13 percent as contract service providers and 13 percent in companies that were suppliers/vendors to biopharma companies. The remaining 17 percent were affiliated with academic institutions, government organizations, or consulting.

The first article in the series looked at biopharma therapeutics, now and in the future (read more). Respondents rated mAbs as the most commercially important biotherapeutic right now, but saw cell and gene therapies as being very promising for the future. We also spoke to four Power Listers about their thoughts on the survey results and their advice on what biopharma needs to focus on to rise to the challenges that lay ahead for the field.

The third and final article in this Biopharma Trends series will consider the future of the biopharmaceutical manufacturing and gather opinions on Industry 4.0 – the fourth industrial revolution.

Is there more universities could be doing to prepare students for careers in the biopharma industry, given the importance of on-the-job practical training? “Yes, if they are willing to spend the money and collaborate with industry,” says Odum. “But the traditional tenured academic research-driven platform does not lend itself to OTJ-type models.”

O’Driscoll thinks that universities should be given credit for what they’ve done to date in supporting and driving the biotech industry from its origins over 30 years ago. “But for sure the industry is changing rapidly,” he says. “Most universities are aware of what industry needs; they’re flexible, they’re responsive, while still making sure that they are teaching the core skills and competencies that are required for graduates – but there’s always room for continuous improvement. That’s why we’re delighted to see what Jefferson are doing in the US and we’re aware of similar initiatives throughout the globe.”

Look out for our third and final article in this Biopharma Trends series, where we look at the future of the industry and opinions on Industry 4.0. Industry 4.0 represents the adoption of intelligent, data-driven approaches, and is already bringing tangible benefits to other sectors. But which elements can benefit biopharmaceutical manufacturing.

Industry 4.0 will also be explored at an upcoming conference to be held in Cork, Ireland, 13-14 November 2018. Find out more at: www.biopharmatrends.com.

Meet the Experts

Killian O’Driscoll is Director of Projects at NIBRT and has been involved in the successful establishment of the Institute, which has numerous international accolades including ISPE Facility of The Year and Bioprocess International Manufacturing Collaboration of the Decade. He is also Associate Lecturer in Project Management at Dublin Business School.

Jeffery Odum has over 25 years of management experience in the design, construction, and commissioning of facilities in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. Jeffery served as the North American Education Advisor to ISPE and is co-Chair of the ISPE Biotechnology Community of Practice. He has led training efforts in fifteen countries, including training for global regulators from the US FDA, Health Canada, and the Chinese SFDA.

Andre Walker is a consultant with over 30 years of experience providing engineering and technical support for manufacturers of biopharmaceuticals, medical devices, and consumer products, including 13 years in Director roles for Biogen with postings in the US and Europe. Andre has served as the Chair of the ISPE International Board of Directors in 2011 and is currently the Chairman of the upcoming BioManufacturing Conference.

Kathleen Gallagher is University Executive Vice Present and Chief Operating Officer, at Thomas Jefferson University, where she leads the operation and administrative aspects at the multiple university campuses, including the university’s campus integration and strategic planning efforts.

Ron Kander, is Dean of the Kanbar College of Design, Engineering and Commerce and Associate Provost for Applied Research at Thomas Jefferson University, USA. He teaches and does research in the areas of materials selection and design, systems dynamics modeling, complex data visualization, and integrative design thinking.

- NIBRT & The Medicine Maker, “Biopharma Trends: Trends in Biopharma Manufacturing Survey Report” (2017). Available at: bit.ly/2lDuHwl.

- EMA, “EU Guidelines to Good Manufacturing Practice Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use: Annex 1 Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products”, (2008). Available at: bit.ly/2vzxDP1.

Over the course of my Biomedical Sciences degree it dawned on me that my goal of becoming a scientist didn’t quite mesh with my lack of affinity for lab work. Thinking on my decision to pursue biology rather than English at age 15 – despite an aptitude for the latter – I realized that science writing was a way to combine what I loved with what I was good at.

From there I set out to gather as much freelancing experience as I could, spending 2 years developing scientific content for International Innovation, before completing an MSc in Science Communication. After gaining invaluable experience in supporting the communications efforts of CERN and IN-PART, I joined Texere – where I am focused on producing consistently engaging, cutting-edge and innovative content for our specialist audiences around the world.