Tackling Serious Organizational Failure

An FDA Warning Letter can be a real wake up call. How can you address the root of the problem to protect against future violations?

Peter Calcott |

Picture this: you are the CEO of a pharmaceutical company and a Warning Letter from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lands on your desk. The letter informs you that your staff have been caught faking data and recommends that you enlist a consultant specialized in evaluating and rooting out fraudulent practices. Of course, you would be shocked; after all, such an accusation attacks the very nature of what we do and the values we hold dear to our heart. But it goes deeper than that. Don’t forget all the patients who were prescribed drugs manufactured by your company. They are likely to be wondering whether the batches they are taking right now are suspect. Even if they examine the drugs, there is no way that a customer can tell if they are good or bad. Trust in both the company and the pharmaceutical in question is lost almost instantly. And it won’t be won back quickly or easily, if at all.

If you think this sounds like an unlikely story, you may be surprised to learn that several companies have already received such Warning Letters in 2014 (1)(2)(3).

Cutting corners

As a CEO or senior executive, your first instinct may be to assume that it’s an isolated incident. But I assure you that it is not; it is endemic in your organization. What could have caused this? The answer is simple: when the drive for volume outweighs the drive for quality, people cut corners to meet the quotas.

After the Warning Letters were issued in the real world examples noted above, the usual posts on LinkedIn followed to broadcast the news. People asked questions and expressed their opinions. After reading several posts, I was perplexed. It seemed that many of the posts focused on ‘advertising’ their services or posting links to websites listing best practices. But in my experience, all the best practices, standard operating procedures (SOPs), policies and tools in the world are not going to solve this problem. At best they will mask the issues and delay the actual remediation.

If the management in these companies is serious about solving the problem, they must wake up and engage with their operations to find the root cause. Unfortunately, the answer is often staring at them in the mirror every morning. The management is the problem. They have lost sight of their goal. They have created an environment where the drive is to increase revenue at any cost. They have altered the company culture, intentionally or unintentionally, losing sight of the customer – the patient.

Rescuing quality

The turnaround to a quality-minded culture cannot be made by rewriting policies and SOPs. It also cannot be made by inspiring speeches at all-hands meetings or emails to staff. Culture change can only come when the workers see the CEO and his staff demonstrating the correct behavior. He or she must not only clearly describe his or her new position and expectation to the staff, but be seen to actually do it.

A turnaround of a company in such dire straits can only come from the top. It takes a brave CEO and senior staff to recognize the problem, fix it and be seen to fix it. As a consultant, I am often asked to help facilitate improvements in an organization’s quality, manufacturing and process development. One of the first things I do is request an interview with the CEO or President (assuming it is not he or she who requested the change), to determine whether those at the top are on board with the change. It is only after I am convinced that the CEO is sincere that I consider taking on the project. And believe me, I have seen my fair share of non-starters. As a consultant, I believe my role is not to rack up billable hours, but to solve problems.

The CEOs I have interviewed under these circumstances fall into three classes. First, there are the ones who ‘get it’ (sometimes they only get it after a severe Warning Letter or worse, sometimes it is just a near miss that has shaken them) – these are the ones I will take on. Second, there are those who simply don’t get it, often returning to the same mindset: “This is going to cost a lot”. Unfortunately, the cost of not making a change is usually much higher and more traumatic. I avoid such CEOs like the plague. The third category is a more difficult beast. They talk about culture change and doing the right thing, but their enthusiasm quickly wanes once they realize they may have to slow down production or set low volumetric goals initially. These ones I try to avoid, if I can spot them early enough.

The successful culture shift

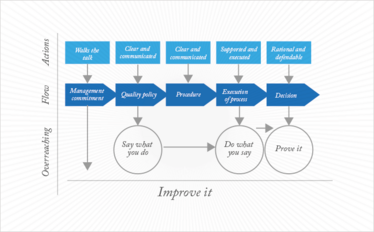

So, how do you go about a culture shift? First, you need to maintain momentum; I use the graphic shown in Figure 1, which allows the organization to see where it is going. The philosophy is based on the adage: “Say what you do, do what you say, prove it, and improve it,” which covers the important elements of documents, execution and records, with a good dose of continuous improvement. It also places the role of management very clearly front and center in the organization.

Figure 1. The linkage between management and actions on the “shop floor”.

As an ice-breaker, I begin the process by giving an overview on a topic of interest to all, such as quality risk management, ICH Q10, or quality by design, to a broad-based group, including quality assurance, manufacturing, quality control, engineering, validation, procurement and logistics. I introduce the program using the graphic in Figure 1 and indicate that we are going to start with a gap analysis. I point out that it is not an audit; there will be no paperwork and corrective action and preventive action (CAPA) reports to manage. I also describe what the culture needs to be like at the end of the project. The sidebar illustrates some of the elements that make up the ideal company culture. With the elements clearly defined, everyone can recognize change as the project progresses.

I interview all the process owners of the quality management system and stakeholders. Basically, I ask them to describe it to me – what do they like, what don’t they like, and what are their frustrations. Otherwise known as The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, after that great spaghetti western! It is important that this discussion is open and honest. All discussions are kept anonymous and identities are not reported to management. The goal is to identify what can be improved, not to identify those who can be blamed. I also look for signs in areas where the desired traits are already evident and take an inventory of which elements are either missing or targets for improvement.

By the time I have conducted these interviews, it is surprising how much I have learnt. Here are some common themes:

- While the organization as a whole engages in ‘silo thinking’, there are usually little pockets where collaboration is evident across functions. We must now develop ways to propagate this across the organization.

- People are relieved that somebody has shown interest in what is not working and that somebody is listening.

- The critiques from the process owners and stakeholders are often identical: everybody knows what does not work. Now that is out, we can work on the solutions.

- In the gap analysis, everybody feels free to articulate. They take the risk to trust. Of course, some are more open to discussion than others. In the early interviews, I learn and in the later ones I often confirm what I have already heard.

- A lot of people have very good ideas on how to solve the issues. Taking these ideas, vetting them, organizing and prioritizing is the easy part. The next step is to form the teams that will work on the solutions, focusing on a collaboration, the elimination of silos, and user-centric design.

Top 10 traits of a high performing organisation

- There is a blame-free culture: we are out to solve problems not punish people.

- Mistakes are a learning experience.

- Silos are eliminated.

- Quality is value added.

- Quality is a facilitator, partnered with to solve problems.

- User-centric systems, processes & documents rule.

- Team-based approaches are encouraged.

- Human error is manifestation of a broken system, not a root cause

- Simplicity rules, complexity is driven out.

- Our QMS is a set of tools to help us accomplish our goals.

Building on success

With the analysis complete and project plans outlined, we get management support to embark on a variety of improvement projects. Some problems are expensive and time-consuming to remedy, while others can be done quite quickly. I always look for some quick wins that can be done inexpensively and with little disruption, alongside longer-term goals. These early successes create momentum in the company.

Let me share a short example of success. One company’s implementation of a CAPA tracking system had not been executed well; the new software was painful to operate and consequently avoided by many in the workplace. In fact, it was not a software problem but rather a configuration issue. A small project with a broad-based team was empowered to create a solution. The configuration was re-engineered, tested and evaluated by a variety of users, then revalidated. An ‘advertising’ campaign followed to describe what had been changed, why it had been changed, and what the impact would be. When the newly configured system was rolled out, people started to clamor to use it. The system was no longer a burden – it was a usable tool set that aided the workflow. Seeing the real impact of the success, the organization was inspired to create improvements in other systems. Staff were energized. The culture shift had begun.

- FDA Warning Letter, USV Limited, WL 320-14-03, February 6, 2014.

- FDA Warning Letter, Canton Labs Private Limited, WL 320-14-0, February 27, 2014.

- FDA Warning Letter, Smruthi Organics Ltd, WL 320-14-005, March 6, 2014.