The (Human) Cost of Greed

To what extent is the pharmaceutical industry responsible for the USA opioid crisis – and the half a million lives lost over the past three decades?

The opioid crisis in the USA has claimed well over half a million lives – more than the num-ber of American soldiers killed in World War II. At its worst, the opioid crisis claimed more lives in a single year than the number of Americans killed during the entire Vietnam war. The scale of the crisis partially explains why average life expectancy in America declined in 2017 – a first for the developed world.

Issues of prescribing, dependence and misuse are complex and overlapping. When taken for a short time and as prescribed by a healthcare provider, opioids are generally safe: many Americans suffering with chronic pain take opioids for much-needed relief without misusing the drugs – indeed they are the majority (1). But opiates can cause changes in neurological pathways in just a few days, and many abuse the medicines they are prescribed by taking too much – in some cases, crushing pills to either inhale or inject the drug instead – or by seek-ing early repeat prescriptions. Others may become dependent on illicit drugs and then seek to replace them with prescribed medicines; while others may become dependent on pre-scribed medicines and then, when they are no longer accessible, seek alternatives from other sources (2).

Tragically, a sufficiently high dose can slow or stop a person’s breathing, which can result in death. No one knows the true number of deaths caused by prescription opioids, including diverted prescriptions or counterfeit medicines that have been imported illegally from other countries; toxicology testing cannot distinguish between some pharmaceutically- and illicitly-manufactured opioids, such as fentanyl. Furthermore, drugs are not specified on the death certificate in approximately 20 percent of overdose deaths. And in 2014, multiple drugs were involved in almost half of the drug overdose deaths that mentioned at least one specific drug on the death certificate (3).

But we do know that more than 50 percent of overdose deaths during the course of the USA opioid crisis were related to prescription opioids. Regardless of how they are taken, these are drugs manufactured by pharmaceutical companies, approved and licensed by regulatory authorities, distributed by wholesalers, and prescribed by medical professionals. And that raises some big questions. How could such harm come from legitimate attempts to treat pain? Why couldn’t the authorities prevent misuse? Will bad actors be brought to justice? What should be done to halt the situation and ensure it never happens again?

The Origin Story: Legitimizing Opioids For Chronic Pain

The global medical community was for a long time cautious about prescribing opioids to treat pain. As Marcia Meldrum notes in an article for the American Journal of Public Health, back in the 1970s, “Physicians and nurses were trained to give minimal opioids for pain, often even less than prescribed, unless death seemed imminent. Chronic pain, a few studies noted, was badly undertreated,” (4). But in the 1980s, the consensus began to shift as a group of pain specialists advocated for better pain management – particularly in cancer patients.

“There was an earlier pendulum swing,” says Tom Frieden, former director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and President and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, an initiative of Vital Strategies. “From after the Civil War until around the 1920s, opioids were widely used, resulted in lots of addiction, and then there was backlash which led, often, to an undertreatment of even severe acute pain over the course of several decades,” he says.

Authur Gale, who practiced internal medicine during the 1970s, believes the US opioid crisis began – insofar as the role of medicine is concerned – with an obscure US Supreme Court decision known as “Goldfarb” in 1975. “This decision determined that medicine (and law) were no longer to be considered professions, but were, in the words of the court, ‘ordinary purveyors of commerce,’” he says. “Before Goldfarb, physicians were very careful about prescribing opioids.”

In 1980, Jane Porter and Hershel Jick wrote a short letter to the editor in the New England Journal of Medicine describing their analysis of 11,882 patients who received narcotics in a hospital. They found that there was only one “major” instance of addiction. The letter became a prominent resource of pain-relief advocates and has been cited more than 900 times (5), despite being only five sentences long.

In an interview for the book “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opioid Epidemic” Marsha Stanton, a nurse, told the author that she and other seminar speakers often cited it during the 1990s. “We all thought it was gospel,” she said (5).

But the original analysis wasn’t a peer-reviewed study – and nor did it look at those patients taking opioids for chronic pain outside of a hospital setting. And in 2017, a bibliometric analysis of the letter (6) found that it was “heavily and uncritically cited as evidence that addiction was rare with long-term opioid therapy.” The authors concluded, “This citation pattern contributed to the North American opioid crisis by helping to shape a narrative that allayed prescribers’ concerns about the risk of addiction associated with long-term opioid therapy.”

Nevertheless, the letter became part of a body of evidence that contributed to changing opinions on opioid therapy for chronic pain, which included two highly influential articles published by Kathleen Foley in 1981 and 1986, reporting on the low incidence of addictive behavior in small groups of cancer and noncancer patients (4). Russell Portenoy had been working under the supervision of Foley and became a vocal advocate for the use of opioids to treat chronic pain – giving talks at conferences and seminars, as well as writing numerous articles and book chapters on pain.

The WHO published new guidelines for treating cancer pain in 1986 – recommending the use of strong opioids in cases of persistent pain after treatment with non- and weak opioids. As prescribing trends matched the new guidelines, a number of publications began to question why opioids were reserved solely for cancer pain (7), including an article in Scientific American titled “The Tragedy of Needless Pain,” which described Jick and Porter’s five-sentence letter to the editor as an “extensive study.”

According to Marcia Meldrum, the best-known alternative to opioids is a “multidisciplinary team approach involving reliance on physical and psychological therapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation and pain-coping skills training, and self-hypnosis,” (4). But such methods are poorly covered by insurance providers in the US. And throughout the 1990s, opioid therapy gained support from experts, government agencies, and national nonprofits. And that opened the door for opioid manufacturers.

Marketing Opioid Therapies

Opioids have been commercially produced since the early 19th century and there were a number of brand name and generics opioids available in the 1980s and early 1990s. But these products only provided short-term pain relief – up to six hours.

Purdue Pharma developed a morphine formulation that could relieve pain for between eight and 12 hours that went off patent in the late 1980s. To avoid generic competition, the company developed an extended release formulation that they claimed would be effective for up to 12 hours: Oxycontin.

Oxycontin was approved by the FDA for moderate-to-severe pain, when an around-the-clock analgesic is needed for an extended period of time. A key decision in the opioid crisis timeline was the FDA’s decision to allow Purdue to claim, on the original label, “Delayed absorption as provided by Oxycontin tablets, is believed to reduce the abuse liability of a drug.” This sentence would form the basis of the company’s marketing campaign and remained on Oxycontin’s label for more than five years before the FDA removed it and added a “boxed warning” on the label to signify the drug’s serious or life-threatening risks (8).

Purdue spent over $200 million on Oxycontin marketing in 2001 alone. Art Van Zee explained how money was spent from 1996 to 2001 in an article entitled: “The Promotion and Marketing of Oxycontin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy” (9). “Purdue conducted more than 40 national pain-management and speaker-training conferences at resorts in Florida, Arizona, and California,” he wrote. “More than 5000 physicians, pharmacists, and nurses attended these all-expenses-paid symposia, where they were recruited and trained for Purdue’s national speaker bureau.”

Another pillar to the marketing plan was the use of data. Purdue used a database of prescriber habits to identify the highest and lowest prescribers of particular drugs in a single zip code, county, state, or the entire country. The company then targeted the physicians who were the highest prescribers for opioids across the country.

As Chris McGreal details in his book, “American Overdose: The Opioid Tragedy in Three Acts,” Purdue sales reps distributed coupons for doctors to give their patients a 30-day free supply of Oxycontin and would arrive at physicians’ offices “loaded with free mugs, fishing hats, even a CD: Get in the Swing With Oxycontin.” Sales of Oxycontin grew during this time from $48 million in 1996 to almost $1.1 billion in 2000.

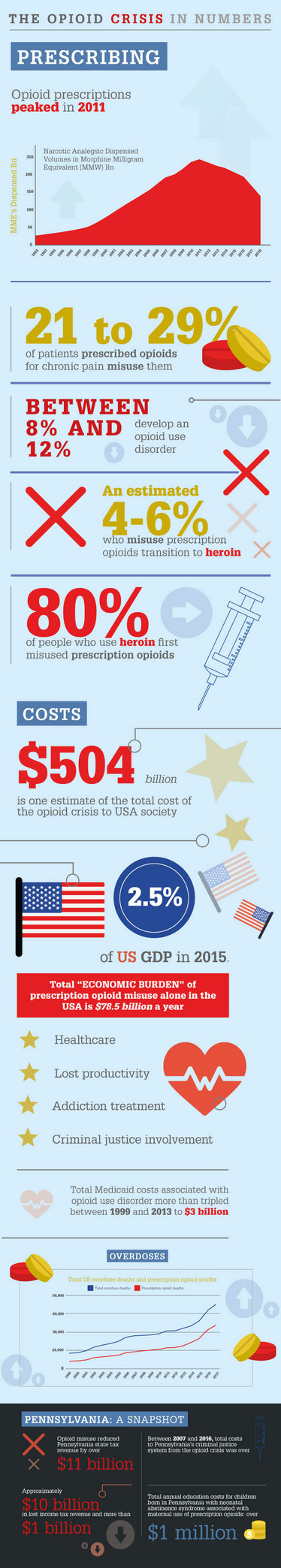

But in 2001, the New York Times reported that a rapidly increasing number of people were bypass-ing the slow release formulation by crushing the pills and either inhaling the drug, or mixing it with liquid and injecting for a quick and powerful high (10). As our sidebar (The Opioid Crisis in Num-bers) shows, 21 to 29 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them, with be-tween 8 and 12 percent going on to develop an opioid use disorder. By 2004, Oxycontin had become a leading drug of abuse in the US (9).

Purdue was aware of the potential for addiction early: over a hundred internal company memos between 1997 and 1999 included the words “street value,” “crush,” or “snort” (10). But it wasn’t until 2004 that the company was first sued – by the West Virginia Attorney General for reimbursement of “excessive prescription costs” paid by the state. The state charged Purdue with deceptive marketing, but the case never went to trial and Purdue agreed to settle with $10 million.

The most significant case came in 2007, when the company pleaded guilty to misleading the public about Oxycontin’s risk of addiction and agreed to pay a $634.5 million settlement. Purdue sales reps had fraudulently downplayed the drug’s potential for abuse – sometimes using fake scientific charts, which they distributed to doctors. Several senior executives of the company paid a total of $34.5 million in fines after pleading guilty to “misbranding” (11).

In May 2018, six states – Florida, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, Tennessee and Texas – filed lawsuits charging deceptive marketing practices, adding to 16 previously filed lawsuits by other US states and Puerto Rico. By September 2019, over 2000 plaintiffs – including 23 states, local governments and Native American tribes were suing Purdue.

At the time of writing, Purdue had reportedly reached a tentative $10-12 billion deal, in which the Sackler family would exit the company before it filed for bankruptcy, dissolved and reformed. But the company could still face legal battles with states not in the deal, such as Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Wisconsin (12).

Beyond Morphine

Another opioid that has made headlines in the US is fentanyl, a fast-acting, high-potency drug that is 50 times more powerful than morphine. Originally, fentanyl was rarely used outside of hospital operating rooms, but following the introduction of a transdermal formulation of the drug in the 1990s, it became an option for chronic pain management. As its popularity increased, alternative forms of the drug, including lozenges, tablets, and sprays were developed for medical use (13).

As these formulations can be more easily mixed with other drugs to increase bulk or potency, fentanyl grew in popularity among drug dealers as a cutting agent for a variety of drugs. From 2010 to 2016, there was a three-fold increase in the proportion of opioid deaths caused by synthetic opioids like fentanyl. By December 2018, fentanyl was the most commonly used drug in overdose cases (14).

One such spray was a sublingual formulation called Subsys, developed by Insys Therapeutics. The FDA approved the drug for “breakthrough pain” in cancer patients that persist after using other medications. Following the approval in 2012, Insys became the US’s best performing IPO, and by 2015, revenue from Subsys approached $500 million (15).

But as MotherJones reports, several Insys employees were simultaneously filing whistleblower lawsuits alleging that the addictive drug was marketed, off-label, to patients who suffered from all kinds of pain, and detailing dubious sales tactics – including, allegedly, taking doctors to strip clubs, encouraging sales reps to sleep with and give lap-dances to doctors, hiring doctors’ significant others, paying kickbacks for more prescriptions, compensating physicians for speaking at events based on the volume of Subsys prescriptions written, and posing as doctors’ representatives to get insurance to cover the drug (15).

On May, 2019, a federal jury found top executives of Insys Therapeutics, including the one-time billionaire John Kapoor, guilty of racketeering charges. They were found to have conspired to fuel sales of Subsys by bribing doctors and misleading insurers about patients’ need for the drug. The company agreed to pay $225 million to settle the federal government’s criminal and civil investigations into the company’s marketing practices. The company filed for bankruptcy 10 days later (16).

A Few Bad Apples?

A central question faces pharma in the wake of the ongoing opioid crisis: can the industry’s contribution be attributed to only a few bad apples or is it a signal of a wider problem?

Thuy Nguyen, Postdoctoral Fellow at the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University Bloomington, US, set out to understand the link between payments to physicians and opioids prescribing on a nationwide scale.

“Well-documented cases and lawsuits of marketing of Oxycontin and Subsys indicate that many opioid-related marketing practices are problematic and tremendously harmful to public health,” says Nguyen. “Our recent paper provides evidence of the problematic role of opioid-related promotion in the US opioid crisis.”

The researchers found that the US doctors who received pharmaceutical payments from 2014 to 2016 prescribed, on average, over 13,070 daily doses of opioids per year more than their colleagues that received no such payments (17). “Although this finding should not be interpreted as causality, this substantial association, together with well-documented cases and lawsuits of marketing of Oxycontin and Subsys, provide support for the necessity of enhanced transparency and efficient restrictions regarding pharmaceutical marketing,”

Nguyen says.

Widespread Litigation

Purdue and Insys are by no means the only companies facing lawsuits related to the opioid crisis. The State of Ohio has taken a number of opioid manufacturers to court, including Teva, J&J, Janssen, Endo, Allergan and Actavis. They allege the companies disseminated deceptive statements about opioids and misrepresented the risks and benefits through marketing schemes.

In the lawsuit, the authors write, “Each Defendant used both direct marketing and unbranded advertising disseminated by seemingly independent third parties to spread false and deceptive statements about the risks and benefits of long-term opioid use.” They cite the example of one of Endo’s ads that included photographs depicting patients with physically demanding jobs like construction workers and chefs, which they say misleadingly implied that the drug would provide long-term pain-relief and functional improvement (18). They also cite a patient education guide, distributed by Janssen, which claimed that “[m]any studies show that opioids are rarely addictive when used properly for the management of chronic pain."

Former Ohio Attorney General, Mike DeWine, claimed opioid companies spent “millions of dollars on promotional activities and materials that falsely deny or trivialize the risks of opioids while overstating the benefits of using them for chronic pain.” He argued that opioid makers were “borrowing a page from Big Tobacco’s playbook” (19).

In a case in Oklahoma, a judge ruled that J&J had intentionally played down the dangers and oversold the benefits of opioids. The company was ordered to pay the state $572 million. There are currently more than 2,000 opioid lawsuits pending across the US pursuing a legal strategy similar to Oklahoma’s.

“In some ways, the J&J opioid lawsuit decision by Judge Balkman is a ‘litmus test’ for future opioid cases,” says Rebecca Haffajee, Policy Researcher at RAND Corporation and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy at the University of Michigan. “The misleading and deceptive marketing behavior that the Judge found J&J guilty of, in violation of the state’s public nuisance law, is behavior this company and many others appear to have engaged in, in other states and locales, where they are defending similar lawsuits.”

The Oklahoma case was interesting in that it potentially sets a precedent for holding a manufacturer legally responsible for creating a public nuisance by selling opioid products. “In the past, this legal theory has been successfully asserted in cases of real property destruction,” says Haffajee. “The outcome of this case may induce opioid manufacturers and distributors to favor settling, rather than going to trial, in other cases to avoid potentially large payouts and negative publicity.”

But Haffajee thinks there are a few reasons to think the Oklahoma case will not “set the rule” for other cases. “Johnson and Johnson plans to appeal the ruling, so it could potentially be overturned; as well, the public nuisance law in Oklahoma is more broad and favorable to the government than are sister laws in other states,” she says. “Other legal theories (such as fraud and unjust enrichment) are more prominent in many other cases.”

Another legal argument being pursued in many states is that opioid distributors did not do enough to stop controlled substances from being misused. A lawsuit in the Cherokee Nation against McKesson, Cardinal Health, Amerisourcebergen, CVS, Walgreens Boots Alliance and Wal-Mart alleges that the defendants “utterly failed” in their duty to “serve as a check in the drug delivery system, i.e., by securing and monitoring opioids at every step as they travel through commerce, pro-tecting them from theft, and refusing to fill suspicious or unusual orders by downstream pharmacies, doctors, or patients,” (20).

McKesson, CVS, Walgreens and Cardinal Health have already paid fines and settlements for the opioid crisis, sometimes multiple times over (21).

The Response

Although the number of drug overdose deaths fell for the first time since the crisis began in 2018, a report by RAND in August 2018 found that the rise of fentanyl and its analogs largely in the Northeast and Midwestern areas of the US could spread (22). The report concludes that problems with synthetic opioids are likely to get worse before they get better. “The US synthetic opioid problem is not yet truly national in scope,” said the authors. “Some regions west of the Mississippi have been less affected to date. Those areas should be seen as at high risk of a worsening problem.” Sadly, reports from San Francisco and Seattle suggest the report’s grim predictions may be coming true (23).

What could be done in the short term to alleviate the number of Americans dying from opioid overdoses? According to Tom Frieden, access to opioid agonist therapy is key. “We need a complete change in the way we enable access to buprenorphine such that it is no harder – and ideally slightly easier – to prescribe than other opiates,” he says. Buprenorphine effectively binds to the same brain receptors as opioids used for pain and is used to lower the potential for misuse, diminish the effects of physical dependency to opioids and increase safety in cases of overdose. “This, combined with barrier-free access to treatment with buprenorphine and methadone, and widespread availability of naloxone, would be the most likely means to rapidly reduce deaths from opiates.”

Longer term, many have called for regulatory responses to the opioid crisis and have argued that the FDA should have done more, or acted differently, during the crisis. For example, the FDA has been criticized for approving Oxycontin’s original label, as mentioned previously. The FDA has also faced criticism for facilitating “regulatory gamesmanship” (26) by approving Purdue’s reformulation of Oxycontin (Oxycontin OP) while at the same time removing the original formulation from the market on safety grounds, thus preventing generic competition and ensuring the continuation of Purdue’s monopoly.

Some have also questioned the FDA’s closeness to the industry. For example, two medical officers, who originally approved Oxycontin, Curtis Wright and Douglas Kramer, went to Purdue Pharma shortly after leaving the FDA.

“Commentators often blame FDA reluctance on capture by the drug industry (and there is certainly some truth to that), but I argued in my paper (27) and elsewhere that the agency is excessively deferential to the medical community and avoids stepping on the proverbial toes of physicians,” says Lars Noah, Professor of Law at the University of Florida, who has been writing about the opioid crisis since 2002. “I continue to focus on primary prevention (ban off-label use and mandate physician certification rather than letting any clown with prescribing privileges and a DEA number hand these out like candy) while recognizing that opiate-use disorder (OUD) treatment is the critical need,” he says.

Tom Frieden also points towards FDA reform. “Congress needs to change the law so the FDA is not forced to approve all medicines which are shown to be equivalently safe and effective,” he says. “The law should also allow the FDA to restrict promotion, advertising, and so-called medical education that actually serves to market products to doctors in ways that are not in the public interest.”

Since 2013, USA manufacturers have had to report their financial ties with prescribers, as mandated by the Physician Payment Sunshine Act. “But a recent paper by King and Bearman (28) suggests that banning or limiting pharmaceutical gifts to doctors are more effective in reducing the influence of marketing on prescribing decisions than disclosure policies alone,” says Thuy Nguyen, Postdoctoral Fellow at the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University Bloomington. “Vermont, Massachusetts and Minnesota already implemented such statutory bans at the state level.”

Nguyen also argues that training of prescribers by academics or public health workers, commonly known as academic detailing, can be considered as an alternative way to provide information of beneficial new drugs with advantages of minimal bias and profit-seeking. “For example, medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUDs) have been found to decrease mortality and morbidity associated with this type of disorder,” she says. “Academics or public health workers without financial ties with manufacturers of these drugs could provide information of the risks and benefits.”

Finally, Nguyen points out that training in the ethics involved in accepting pharma manufacturer financial incentives should also be considered, as prior research has shown that attending a medical school with a gift restriction policy reduces the prescribing of marketed products (28). “Continuing ethical education can enhance prescribers and medical staff’s awareness of potential conflicts of interest and help them to effectively resolve or manage these conflicts,” she says.

The Big Picture

It is important not to forget about the millions of Americans who suffer with chronic pain and take opioids for much-needed relief. There is an important distinction to be made between being “dependent on” and misusing a drug: there are many patients that legitimately need and take opioids – sometimes increasingly stronger drugs over time. As mentioned previously, they are the clear majority of patients taking opioids. Any efforts to curb opioid approvals or prescriptions should be wary of leaving such patients without help.

Indeed, new CDC guidelines in 2016 advised clinicians to prescribe the lowest effective dose of an opioid and to monitor carefully for benefit and risks when considering dose increase. But, as Beth Darnall argues in Pain Medicine, some healthcare organizations and states have misapplied these guidelines to mandated opioid tapering in patients taking long-term opioid prescriptions (29). Darnall states that this has led to “serious and grave patient harm” and notes “reports of depression, suffering, and patient suicides during forced opioid tapering have increased at alarming rates, and advocacy groups have begun curating patient suicide registries.”

Those arguing for the expansion of opioid treatments did not always adequately report the potential for misuse. And the opioid crisis raises painful questions about the actions of pharma companies and conflicts of interest within regulatory bodies and the healthcare profession. But it must not be forgotten that the original expansion was in response to a real public health problem: chronic cancer pain.

Eighty percent of patients with advanced cancer experience moderate to severe cancer pain, and approximately 55 percent of patients with cancer and 40 percent of survivors experience chronic cancer-related pain. Yet a recent meta analysis of 122 studies found that one-third or more patients with cancer and survivors are having difficulty getting access to their prescribed opioid medications and that the proportion of people experiencing such difficulties has increased markedly since 2016 (30).

But Frieden goes so far as to say chronic pain should rarely if ever be newly treated with opioids. “Opioid naive patients (patients who have never been on an opioid) should be treated with physical therapy, local measures, Tylenol, Motrin or other NSAIDs, and cognitive-behavioral therapy instead – these alternatives all work and are much safer than opioids. They preserve function better, and, unlike opioids, don’t potentiate and increase pain perception,” he says. “For people on opioids, measures to reduce the risk of fatal overdose are key. And for those who are addicted, increasing access to effective treatment can save lives.”

In the coming years, the healthcare profession will have to reconcile the need for effective treatments for individuals suffering with chronic pain and the tremendous costs of the opioid crisis – especially in terms of human life, the impact on families and communities, as well as society at large.

An International Issue

Eighty percent of the world’s prescription opioids are consumed in the USA, but it isn’t the only country with opioid misuse problems. That said, the USA’s death rate is double that of the Nordic and Anglophone countries, which have the next highest rates, and more than 27 times higher than in Italy and Japan. On average, drug overdose death rates in the USA are 3.5 times higher when compared to 17 other high-income countries (24).

According to the authors of the study, this phenomenon is fairly recent – “in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Nordic countries had the highest levels of drug overdose mortality,” they said.

The researchers found that, in terms of its trends in and age profile of drug overdose mortality, Canada is the country that most closely resembles the USA, with prescription opioids playing a “key role” in driving drug overdose mortality in both countries.

Canada is the second highest per capita user of prescription opioids in the world. Fatal overdoses in Ontario, Canada’s largest province by population, are almost as common as in the USA and roughly twice as common as in England and Wales (25). Canada also has problems with street fentanyl, often produced overseas. According to David Juurlink, Head of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto (quoted in the BMJ), the street fentanyl problem is “a response to the demand created by doctors prescribing opioids so wantonly for the past 20 years.”

The authors list several factors contributing to high USA drug overdose mortality:

Health care system factors:

- Other countries typically placed greater restrictions on strong opioids like oxycodone for non-cancer pain treatment

- Regulations regarding opioid use in European countries included: dose limits, requirements that patients be registered to receive opioid prescriptions, use of duplicate or triplicate prescription pads, and use of special prescription forms

- Reimbursement policies in the USA promote greater reliance on opioid prescribing because insurers in the USA are more likely to cover prescription drugs for chronic pain than alternative therapies, which may be classified as “experimental”

- Prescription opioids are the lowest-cost option for many patients in the USA

- The USA appears to be an outlier in terms of the use of psychotropic drugs, including benzodiazepines, which act synergistically with prescription opioids to increase mortality

- Fee-for-service is the dominant payment method in the US, whereas the set of countries with the lowest drug overdose mortality (Austria, Italy, Japan, Spain, and Portugal) have a much greater reliance on capitation or salary systems

- It is more difficult for physicians to identify doctor shopping due to the poor quality, lack, or underutilization of centralized administrative patient records, and prescription drug monitoring programs remain underused and vary in terms of quality and completeness across states

Pharmaceutical industry factors:

- Opioid prescribing can also be motivated by pharmaceutical advertising and marketing; and only the US, New Zealand and Brazil permit direct-to-consumer advertising

- The majority of new drugs are approved in the USA before other countries and all five countries with the lowest drug overdose mortality approved Oxycontin fairly late and have relatively low approved maximum dosage forms

Drug policy factors:

- The USA favors abstinence-only policies, which (according to the authors) have been hypothesized to contribute to riskier drug use, less access to treatment, and higher drug overdose mortality

- Compared with other countries, the USA has a much lower percentage of opioid-dependent patients in treatment

- Buprenorphine is expensive and difficult to access in the US. France’s policy to allow all registered medical doctors to prescribe buprenorphine without any special education or licensing was associated with a tenfold increase in patients being treated and a 79 percent reduction in opiate deaths

Other factors:

- In an environment where patients have wide choice and can easily change providers, physicians have stronger incentives to placate patients by prescribing painkillers

- The USA has a higher prevalence of pain-related chronic diseases and disability

- Poor macroeconomic conditions contributing to unemployment, deindustrialization, and downward intergenerational mobility

- ND Volkow and AT McLellan, “Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain — Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies” N Engl J Med, 374, 1253-1263 (2016).

- Public Health England, “Dependence and withdrawal associated with some prescribed medicines” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2o7Wx8t. Accessed October 16, 2019.

- P Seth et al., “Quantifying the Epidemic of Prescription Opioid Overdose Deaths”, Am J Public Health, 108, 500-502 (2018).

- ML Meldrum, “The Ongoing Opioid Prescription Epidemic: Historical Context”, Am J Public Health, 106, 1365-1366 (2016). PMID: 27400351.

- Drug Rehab, “The Opioid Epidemic” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2kiTtVg. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- PTM Leung, “A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction”, N Engl J Med, 376, 2194-2195 (2017). PMID: 28564561.

- MR Jones et al., “A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine”, Pain Ther, 7, 13-21 (2018). PMID: 29691801.

- Marketplace, “How one sentence helped set off the opioid crisis” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2m29z67. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- AV Zee, “The Promotion and Marketing of Oxycontin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy”, Am J Public Health, 99, 221-227 (2009). PMID: 18799767.

- The New York Times, “The Alchemy of Oxycontin”, (2001). Last accessed 12 September, 2019. Available at: nyti.ms/2veWmdr.

- The New York Times, “In guilty plea, Oxycontin maker to pay $600 million” (2007). Last accessed 12 September, 2019. Available at: nyti.ms/2u0iCYC.

- BBC, “Purdue Pharma reaches tentative agreement to settle opioid cases” (2019). Available at: https://bbc.in/2mnL2J7. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- Verywellmind, “Fentanyl Analogs and Derivatives in the Epidemic” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2kPVhW9. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- CNN, “Opioid Crisis Fast Facts” (2019). Available at: https://cnn.it/2CNL6Eg. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- Mother Jones, “‘Behave More Sexually:’ How Big Pharma Used Strippers, Guns, and Cash to Push Opioids” (2018). Available at: https://bit.ly/2smNyiJ. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- Guardian, “Opioid manufacturer Insys files for bankruptcy after $225m settlement” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2kiUWee. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- TD Nguyen, WD Bradford, and K Simon K, “Pharmaceutical payments to physicians may increase prescribing for opioids”, Addiction (2019).

- Common Pleas Court of Ross County, Ohio Civil Division (2017). Available at: https://bit.ly/2m1lqBn. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- Vox, “The thousands of lawsuits against opioid companies, explained” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2MGM0sm. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- The District Court of the Cherokee Nation (2017). Available at: https://bit.ly/2kHhaHh. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- JY Ho, “The Contemporary American Drug Overdose Epidemic in International Perspective” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/33x6wUb. Accessed October 16, 2019.

- RAND, “The Future of Fentanyl and Other Synthetic Opioids” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2mmoWGT. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- Hepmag, “Opioid Deaths May Be Falling, but Fentanyl Is Moving West” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2kSgu1w. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- JY Ho, “The Contemporary American Drug Overdose Epidemic in International Perspective” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/33x6wUb. Accessed October 16, 2019.

- BMJ, “Canada’s prescription opioid epidemic grows despite tamperproof pills” (2015). Available at: https://bit.ly/2pt5KZm. Accessed October 16, 2019.

- SLS, “Purdue Pharma & Oxycontin: Regulatory Gamesmanship? A Debate” (2019). Available at: https://stanford.io/2kiVNeW. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- Lars Noah, “Federal Regulatory Responses to the Prescription Opioid Crisis" (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2lSDJc5. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- King et al., “Medical school gift restriction policies and physician prescribing of newly marketed psychotropic medications: difference-in-differences analysis” BMJ, 346, f264 (2013).

- BD Darnall, “The National Imperative to Align Practice and Policy with the Actual CDC Opioid Guideline” Pain Medicine (2019).

- R Page and E Blanchard, “Opioids and Cancer Pain: Patients’ Needs and Access Challenges” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2BhYVNe. Accessed October 16, 2019.

Over the course of my Biomedical Sciences degree it dawned on me that my goal of becoming a scientist didn’t quite mesh with my lack of affinity for lab work. Thinking on my decision to pursue biology rather than English at age 15 – despite an aptitude for the latter – I realized that science writing was a way to combine what I loved with what I was good at.

From there I set out to gather as much freelancing experience as I could, spending 2 years developing scientific content for International Innovation, before completing an MSc in Science Communication. After gaining invaluable experience in supporting the communications efforts of CERN and IN-PART, I joined Texere – where I am focused on producing consistently engaging, cutting-edge and innovative content for our specialist audiences around the world.