The Price of the PBM

There are many players in pharmaceutical pricing, from drug manufacturers to PBMs and pharmacies. Who should take the lead?

Mallikarjun Chityala | | 5 min read | Opinion

Considered a superpower – with the world's largest economy and most powerful military, the US also has one of the world's most expensive healthcare support systems. As per an article in Bloomberg QuickTake (1), the average American spends $1,300 on prescription drugs annually. In fact, Americans spend more on prescription drugs than any other country in the world.

One prime example is the ever-rising price of insulin, which burdens millions of US diabetics. A study by Yale researchers (2) published in Health Affairs in July 2022 suggests that around 14 percent of insulin users in the US spend 40 percent of their post-subsistence family income on insulin alone.

However, a surprising development occurred at the beginning of this year when three of the largest insulin manufacturers in the United States—Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi—announced (3) that they would limit or lower the pricing of a number of their medications in response to years of public criticism and political pressure.

This decision relieved many insulin users but was thought to be a planned escape by pharmaceutical companies for the 2024 Medicaid rebate scheme, which penalises companies who raise prices faster than inflation, thus helping them to cut their taxes by lowering costs.

What's more, per capita spending on healthcare in the US (4) is $10,921, which represents 150 percent more than Japan and 1000 per cent more than India and South Africa, as per the report provided by the global economy for 2019

But not everyone can afford the high cost. A national poll performed by NORC at the University of Chicago and the West Health Institute and presented during the 2018 Aging in America Conference showed that 40 percent of Americans were skipping doctor's appointments and medical tests and under-dosing on prescribed medicines to save money.

Why is the US healthcare system so dysfunctional? Does the government need to impose laws or take corrective action against the red tape and lack of transparency in the cost build-up involved in the process of pharmaceutical products reaching patients? Certainly, the complex process of pharmaceutical pricing involves many players: drug manufacturers, wholesalers, insurers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and pharmacies.

The Medicines Use and Spending in the US report (5) quoted net revenue earned by drug manufacturers as $323 billion in 2016 after excluding rebates and discounts, including those paid to PBMs and other channel intermediaries. A large sample of pharmaceutical companies provided this information for IQVIA's 2016 analysis, accounting for around 67 percent of retained revenue across the US pharmaceutical sector.

In many ways, the world depends on the US for research infrastructure, innovation, and clinical trials, and the high costs (and profits) of medicines in the US are used to invest in these areas. The US drug patent system protects the investment of drug companies by offering exclusivity for an extended period. Some stakeholders point to this as the reason for high prices, but many other elements exist in the US drug market.

One crucial element of the US drug supply chain is the wholesaler, who purchases drugs from manufacturers using purchasing power to gain discounts that average around 16 percent, according to IQVIA data (6). About 92 percent of prescription drugs are distributed through the three largest pharmaceutical wholesalers, McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal. Wholesalers earn revenue through "forward-buying," purchasing extra inventory at current prices to sell them in future at a revised higher price.

And then some insurers serve consumers covered by their insurance with copays. These copays are differential and depend on the cost-effectiveness of the drug. Finally, most insurers connect with PBMs – the experts in drug cost negotiation and the creation of tiered formularies.

Indeed, PBMs are hired as intermediaries between pharmacists and insurance companies, and they are supposed to help reduce costs for consumers and patients of all medications. But, in my view, the current compensation method for PBMs is detrimental to healthcare and society. The main job of a PBM is to create formularies of covered medicines and sort them in order of priority for health insurers. Placing their drug on this formulary is a "make-or-break" situation for a pharmaceutical company. As such, pharma companies offer discounts to PBMs through rebates to ensure their drug gets covered and is prioritised.

PBMs earn dividends from rebates after every product purchase. Therefore, instead of lowering drug costs, a PBM's interest often lies in inflating drug prices to gain more significant rebates. This strategy has completely changed the focus of pharmaceutical companies; instead of competing for good quality, affordable medicines for patients, pharma companies are more interested in appeasing PBMs for the leading position on formularies by offering heavy incentives and pushing higher prices.

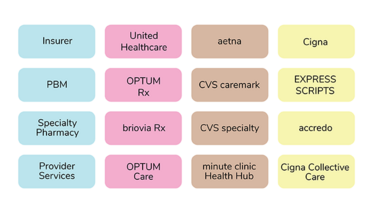

Additionally, the largest PBMs, speciality pharmacies, and insurers are all vertically integrated (7); this is a significant concentration of purchasing power, accounting for the three largest PBMs (8) controlling 80% of the market of prescription volume.

The below graphic provides vertical business relationships among insurers, PBMs and retail chains:

These groups are further expanding. For example, Optum, a part of UnitedHealth Group, employs or contracts 46,000 physicians. That's 5% of the one million doctors in the United States.

Another reason for inflated drug costs? Spread pricing and gag clauses. In spread pricing, if the fee paid by the policyholder is more than the actual claim, then the PBM has to pay the pharmacy for the medications. Furthermore, the gag clause prevents pharmacists from advising consumers about lower-cost alternatives.

There's plenty of blame to go around in the pharmaceutical supply chain, and things are clearly incorrect. However, clarity on PBMs' rebates is necessary for a complete understanding of pharmaceutical costs and opportunities for improvement. It's about time PBMs should move their attention from rebates to pharmaceutical expenditure value. One solution to lower drug prices for better patient care could be to abolish the rebates offered to PBMs for negotiation with the manufacturers and strictly work on a fixed price structure. Health plans and PBMs must promote the prescription of the most cost-effective formulary drugs by focusing on patients' best interests rather than profits.

- R Langreth, “Why Prescription Drug Prices in the US are So High”(2022). Available at: http://bit.ly/3mdE4p8

- B F. Bakkila et al., “Catastrophic Spending On Insulin In The United States, 2017–18”, Health Affairs (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/436ctqy

- B Lovelace Jr, “For many insulin users, new price cuts will be a ‘lifeline’” (2023). Available at: https://nbcnews.to/3UeD8Oa

- The Global Economy.com, “Health spending per capita - Country rankings”. Available at: http://bit.ly/40JxTbq

- Nancy L. Yu et al., “Spending On Prescription Drugs In The US: Where Does All The Money Go?”, Health Affairs (2018). Available at: https://bit.ly/3manC9k

- A Roy, “Drug Companies, Not ‘Middlemen’, Are Responsible For High Drug Prices” (2018). Available at: http://bit.ly/3UqnwHv

- Drug Channels,” Insurers + PBMs + Specialty Pharmacies + Providers: Will Vertical Consolidation Disrupt Drug Channels in 2020?” (2019). Available at: http://bit.ly/3KzCjvV

- Healio, “Vertical integration secures PBMs as ‘arsonists and firefighters’ of drug prices” (2022). Available at: http://bit.ly/3KztUZq

CEO, Fitabeo, UK