Anthrax: an Unlikely Ally

Work in mouse models has found that toxins from anthrax can work as alternative treatments for pain

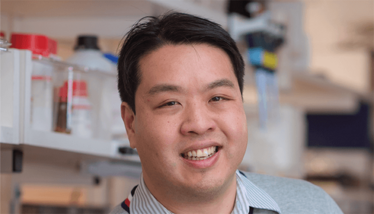

Isaac Chiu is very much a Boston bioscientist. After growing up in the city, he studied undergraduate biochemistry at Harvard College, completed his PhD in immunology at Harvard, undertook postdoctoral training in neuroscience at Boston Children’s Hospital and, since 2014, has run a lab at Harvard Medical School. We spoke with him about his lab’s recent finding (1) that anthrax toxins could form the basis for a new kind of painkiller.

How did you arrive at such a counterintuitive conclusion?

Science is fun precisely because you make unexpected findings.

I’m interested in how neurons interact with microbes because I discovered during my postdoctoral work at Boston Children’s Hospital in Clifford Woolf’s lab that pain can be directly caused by bacteria. In the Chiu lab, we are interested in the mechanisms by which nerves are activated to produce pain. By studying microbes, we hoped to uncover new insights – and potentially new treatments – based on the biology of pain.

While analyzing gene expression data to learn how neurons might detect microbes, we were surprised to learn that the receptor for anthrax toxins, ANTXR2, is expressed by pain-mediating sensory neurons. Now, it just so happens that one of the world leaders in anthrax toxin research, John Collier, works in our department! After teaching me a little about this toxin, he connected me to other key collaborators, such as Steven Leppla of the National Institutes of Health, who are also experts in anthrax toxins.

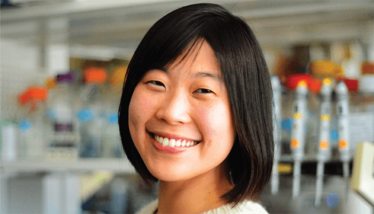

Nicole Yang

Without further input from leading neurobiologists including Bruce Bean, Tim Hucho, and Michele Puopolino – not to mention the outstanding contributions from our postdoctoral fellow, Nicole Yang – this work would simply not have been possible. All science is done as a community these days and our work, which spans the fields of microbiology, neurobiology, and immunology, absolutely requires such dynamic collaborations!

What is the 101 on the science of this study and its findings?

Bacillus anthracis is a bacterial pathogen that causes anthrax. It normally causes skin infections that produce painless, coal-like black lesions. Very rarely, it can cause lethal inhalation anthrax. It mainly causes damage through the production of anthrax toxins, which have three components. The first component, protective antigen (PA), binds to ANTXR2 receptors on certain cells in the body. It then delivers into those cells one of two other possible toxin components: edema factor (EF) or lethal factor (LF).

In our study, we found that anthrax toxins, particularly PA and EF, can target pain fibers in animals and block pain signaling. This is due to the fact that those pain-sensing neurons, called nociceptors, express higher levels of ANTXR2 than other types of neurons. Based on this finding, we injected anthrax toxins into the spines to target the dorsal root ganglia of mice where pain fibers reside – and found that this silenced pain signals caused by either inflammation or nerve damage.

Does this mode of silencing come with any caveats?

We injected the anthrax toxins specifically into the cerebrospinal fluid so that we could contain their spread within the nervous system. There, they can only target pain fibers, thanks to the high ANTXR2 expression. We also found that we could change the cargo linked to the anthrax toxin so that it carries other types of molecules into those pain fibers – including botulinum toxin, which can block neurotransmission. This finding was possible in part thanks to French company Ipsen Pharmaceuticals, who helped us create the hybrid anthrax toxin-botulinum toxin cargo.

After reflection, what’s next?

Our research has raised new questions. Are there other microbial products out there that could act on neurons to treat disease, whether by altering pain or other neurological functions? As far as I am concerned, I would love to develop anthrax toxins as a new platform to target neurons and continue to work on loading different proteins into them.

The possible pharmaceutical applications are striking. With a newfound ability to target molecules into pain fibers, we could create new ways of treating pain. At present, pain treatments are not very specific to pain fibers, and drugs such as opioids trigger off-target effects. We are hopeful that this anthrax toxin platform could deliver new drugs into neurons to block pain more specifically.

Thinking more broadly, I believe the American opioid crisis highlights the need for better non-opioid analgesic painkillers. There are many people suffering from chronic pain not just in the US, but across the world. As long as that remains the case, there will be a need for effective, non-addictive treatments. Perhaps developing these treatments will require scientists to mine the natural world – including bacteria.

- NJ Yang, Nat Neurosci, 25, 168 (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-021-00973-8.

Between studying for my English undergrad and Publishing master's degrees I was out in Shanghai, teaching, learning, and getting extremely lost. Now I'm expanding my mind down a rather different rabbit hole: the pharmaceutical industry. Outside of this job I read mountains of fiction and philosophy, and I must say, it's very hard to tell who's sharper: the literati, or the medicine makers.