Russia and Ukraine may not be the central pillars of the global pharmaceutical industry, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t important. Until the Russian invasion of Ukraine, both were host to large and important segments of ongoing clinical trials. As the war drags on in Ukraine, and as Russia is battered by economic sanctions and disengagement, the future of these trials remains uncertain, at best.

To help paint a picture of the ongoing disruption, clinical data company Phesi has published a report revealing the nature and number of clinical trials taking place in the two countries (1). We spoke to Gen Li, Phesi Founder and President, to better understand how these numbers can be used to respond to our era of burgeoning crises.

What’s the source of your data?

We use extensive artificial intelligence and big data from all four corners of the internet – 90,000 sources and counting – to gather and tabulate the data our company uses. Next in our process comes a great deal of cross checking, cross referencing, and contextualization. By and large, we collect clinical trial data, which covers all of the relevant operational details and also patient data, both in clinical research and community development settings. We have data from over 40 million patients, and the number continues to grow.

The data we used for our report on disruption in Ukraine, Russia, and their neighbors makes up one relatively small part of that data, which we zoomed in on. We also focused our analysis on commercial industry-sponsored trials, as these are the most important source of innovative treatment options for patients.

What levels of disruption are you seeing?

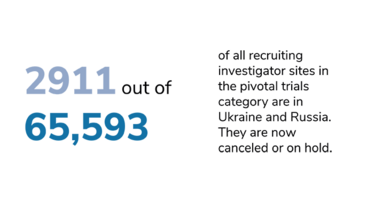

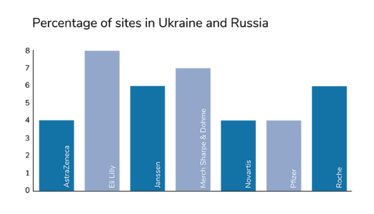

Around 4 or 5 percent of all clinical trials in the world have been put on hold. At a first glance, that might not seem like an especially large chunk. However, the significance of this impact is not evenly distributed. When we take the phases of clinical development into account, we see that phase III has been hit the hardest, proportionally. And that means the economic development of new medicines and the companies working on them have suffered the largest proportion of disruption. Notably, the companies who have leaned hardest into globalization have taken the biggest hits; for example, Eli Lilly had 7 percent of their trial sites based in Russia and Ukraine.

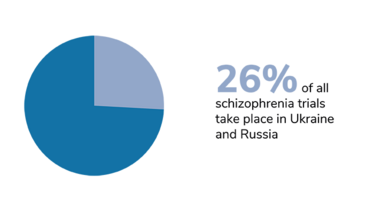

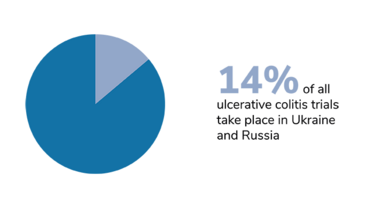

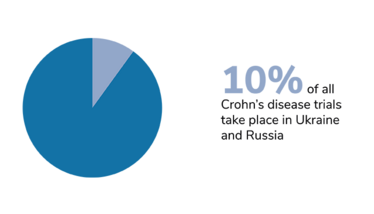

We should also bear in mind that trials of certain diseases have also been disproportionately affected, and that the impact of Russia’s invasion has taken different forms in different countries. In Ukraine, the first priority right now is to protect the patients. The second priority – when the situation allows – is to take care of data integrity, and salvage whatever can be salvaged. Personally, I am hoping for a return to something resembling normality. I hope that the war will stop, the rebuilding process will begin, and the refugees will be able to return home.

The longest-lasting impact of this war will probably be felt in Russia. It has ended up rather isolated from the rest of the world, and will likely remain that way for no short period of time, even if the war were to end tomorrow. I expect Belarus will find itself in a similar situation.

In Poland and other neighboring countries, the main impact will be the influx of refugees. They are going to put an unimaginable burden on the socioeconomic systems in those places. Inevitably, that will lead to harder-to-quantify forms of disruption across all industries. The scenario I pray we will not see is the expansion of the war beyond the borders of Ukraine. Should that happen, we’ll see a huge downtown and the increasing likelihood of various worst-case scenarios.

How do you feel about calls for economic disengagement with Russia?

War and the invasion of another country are matters we should absolutely condemn, without ambiguity or reservation. That said, there are still patients suffering in Russia, in Ukraine, and in every country in the world. It’s our human duty to make sure that these patients are still being taken care of to the furthest extent possible.

Different diseases have different prevalences in different populations. If we exclude particular populations from our trials, we are damaging the universal applicability of the medicines we work to produce.

Having said all that, it is hard to see what – if anything – we will be able to do or would wish to continue doing in Russia. In the short and long term, I think we will need to combine the wisdom from our leaders in government and elsewhere to work together, and see what the best solution will be for patients in Russia.

What do you think are the most likely futures for pharmaceutical operations more generally in Russia and Ukraine?

One way to plan for the future is to learn from the past, but to do so one must be careful and meticulous, documenting all our past choices and actions in data. It’s by bringing a quantitative approach to our analysis of the past that we can be most ready for possible futures. I’m hardly speaking in the abstract; right now, we are facing war in Europe and an ongoing pandemic. It’s all but certain that more challenges await us down the road.

It’s also looking likely that our ideal base of patients is going to continue to shrink for a variety of reasons. COVID-19 has seriously impacted the willingness of patients to sign up to clinical trials and even physicians have become more reluctant to participate. War is having much the same effect in and around Ukraine. Globalization is absolutely at a standstill at this point, and we need to face up to that.

We need to make extensive use of data wherever we can to cut down on inefficiencies. For example, we could find a means to reduce placebo patients or active comparator patients. I’d like Phesi to play a role in dealing with the shrinking patient base by tackling these sorts of tasks.

Preview Image credit: Bruno Pires / Pexels.com

A Grinding Halt

Figures from Phesi’s report highlight disruption to clinical trials in Russia and Ukraine

- 1. Phesi, “New Phesi data highlights potential long-lasting impact from war in Ukraine on global clinical development”, Phesi (2020). Available at: https://bit.ly/cli-ukr-rus

Between studying for my English undergrad and Publishing master's degrees I was out in Shanghai, teaching, learning, and getting extremely lost. Now I'm expanding my mind down a rather different rabbit hole: the pharmaceutical industry. Outside of this job I read mountains of fiction and philosophy, and I must say, it's very hard to tell who's sharper: the literati, or the medicine makers.