Leading the Way with Lipids

Developing new drugs to treat and cure patients is what pharma does. But this task has become significantly more difficult with discovery pipelines pumping out increasing proportions of drugs with bioavailability or solubility issues. How is this changing the field of oral drug delivery? And what are the solutions?

Any technology field is subject to continual change – and oral drug delivery is no different. A 2012 analysis showed that in the year 2000, less than one drug was approved per billion US dollars of R&D spending (1). In addition to rising drug development costs, the so-called “patent cliff” of ~2000 led to increased generic competition and lower prices that forced the pharma industry to adopt cost-containment measures and smarter approaches to drug development and manufacture. To this day, cost pressures remain with drug prices constantly in the spotlight. In addition, patients are ever-demanding more effective and patient-centric medicines.

One response to industry challenges has been the “virtual model” where different aspects of drug development are outsourced to specialty companies, instead of a single company handling the complete drug development process. Increasing numbers of academic spin-offs and small specialty biotechs and pharma companies are entering the field – and although they may have innovative ideas and approaches, they often don’t have the requisite formulation expertise. And the right formulation approach for a given drug is essential to help make it a commercial success. “Rather than getting very well-characterized APIs from large pharma, we are seeing more and more discovery-type compounds,” explains Derek Bush, Manager, Product Development, at Catalent Pharma Solutions.

Bush has seen a marked increase in the number of projects requiring early stage in-vitro screening, with, for example, the aim of establishing in-vitro in-vivo correlation values to guide Phase I clinical studies. These small “discovery” companies are often significantly resource-limited and may have a lot riding on one drug candidate. As such, formulators are under great pressure to ensure that preclinical studies (in-silico and in-vitro screens, and pharmacokinetics work in animals) produce data that will reflect API performance in humans. “These companies can’t afford to repeat their first-in-human trials due to poor formulation,” says Bush. “Their next funding round – and their survival as a company – may depend on getting it right first time.”

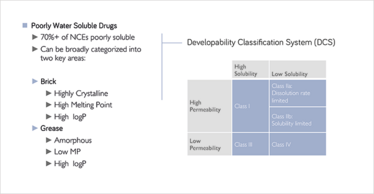

Figure 1: The solubility and bioavailability challenges. Future NCEs continue to exhibit poor water solubility. © BASF

Access to top-flight formulation expertise for early stage drugs is essential, but the problems faced in early development are becoming more challenging. “Drug discovery programs are generating increasing proportions of complex APIs that fall into Class II-IV (poorly water-soluble and/or poorly permeable) of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). Some of the drugs we have found ourselves working with are less water soluble than sand!” says Frank Romanski, Global Technical Marketing – Pharma Solutions at BASF.

Only a small proportion of molecules in the development pipeline are thought to have both adequate solubility and permeability, and many require sophisticated formulation technology if they are to reach their therapeutic targets in-vivo. The problem of bioavailability is further complicated by practical, patient-related considerations – not least, the linked issues of patient acceptability and regimen compliance. “It is not sufficient to make a compound more soluble if the excipients necessary to do so result in a large 5 g dosage form that then has to be split into many smaller tablets or capsules,” says Romanski. “Increasingly, formulators are being required to turn highly lipophilic or highly crystalline early-phase APIs into drug products that are both bioavailable and reasonably convenient to administer.”

Technology takes the strain

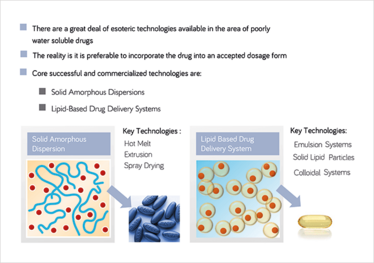

Problems with solubility, permeability and bioavailability have plagued the industry for decades, but the industry is not standing still. Romanski explains that he has seen formulation technology evolve from its simplest form – in which an API is mixed with standard powdered excipients and pressed into a tablet – into the more advanced methods favored by industry today, such as lipidbased drug delivery systems, hot melt extrusion and spray drying. “There is now a range of options available to formulators, depending on where the drug falls on the spectrum of physicochemical properties,” says Romanski. “Liquid oral dosage forms, in particular, have become increasingly exciting, with technology moving on from simply solubilizing a dug in soybean oil and encapsulating it in soft gelatin. Now, we have access to complex, self-emulsifying, as well as digestible, systems that incorporate several interacting excipients.” These types of sophisticated chemistry serve to not only physically stabilize the drug (when formulated as a self-emulsifying drug delivery system) while it is on the shelf, but also when it is released into the aqueous milieu of the gastrointestinal tract after rupture and dissolution of the capsule. Indeed, ensuring that the drug remains solubilized in the GI tract in a form optimized for efficient uptake, such as a population of nano-droplets, is a critical aspect of formulation.

Bush has also observed critical advances in formulation technology and highlights recent developments in modelling and screening technology. “In-silico models that can predict the BCS class of an API (i.e., if it will be solubility-limited or perhaps permeability limited) are incredibly useful,” he says. “The virtual screening route has obvious advantages where time or physical materials are limiting, as is the case for many venture-funded discovery companies. We are also seeing tremendous advances with in-vitro technology. Real-time data analysis, real-time particle size analysis, real-time dissolution testing through fiber optic analysis, lipolysis testing to assess how lipid-based formulations are digested… all of these techniques not only speed up early phase development, but provide information critical for early phase clinical study design.”

And technology is not the only driver helping to advance the formulation field; Romanski says that excipients also have an important role to play. “Excipients are no longer passive carriers or so-called ‘inactive ingredients’. Many in the industry now recognize that excipients have an absolutely fundamental role. In terms of the final product, the excipient may be as important as the API, especially for BCS Class 2 or class 4. For poorly soluble and poorly permeable products, you must rely on excipients to make a functional product. Not only do these ingredients directly interact with the API to ensure bioavailability, but one must also consider how they interact with each other so as to maintain a highly complex dosage form over time.”

Bush agrees, adding, “Our experience is that, without correct attention to excipients, drugs coming out of solution are often more ‘difficult’ than when they were first formulated – perhaps less soluble, for example. It is imperative to ensure that your excipients stabilize the API as the more soluble crystal or amorphous form, not the most stable crystal.” These type of polymorphism challenges can usually only be addressed by applying advanced excipient expertise to ensure that the API is stabilized in the amorphous form or in the precise crystalline form of interest.

More advanced excipients can also confer a range of properties on the drug above and beyond solubilization, including product controlled release properties such as sustained, enteric, or delayed release. This could be particularly useful for acid-labile APIs, where drug release must be targeted to a specific region of the GI tract so that the API can avoid destabilizing pH levels. Finally, where the effects of first-pass metabolism are a consideration, well-designed formulations can potentially direct the drug to the lymphatic uptake, thus avoiding liver enzymes.

Figure 2: Successful techniques for poorly water soluble drugs. Despite the multitude of technologies available, traditions remain. © BASF

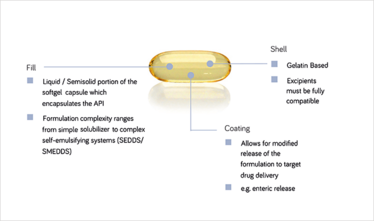

Figure 3: Softgel capsules are well matched as an oral drug delivery vehicle for lipid systems. © BASF

Lipid formulations

A number of different technologies exist to help with formulation challenges, but according to Romanski and Bush, lipid based drug delivery systems (LBDDS) are one of the most commercially successful drug development technologies in the industry – and have helped bring more than 50 poorly soluble new chemical entities to the market. Lipid-based formulations have an outstanding ability to solubilize hydrophobic compounds and also offer the possibility of protection for unstable compounds. “Lipids also avoid first-pass metabolism in certain cases and are one of the only ways to target lymphatic uptake,” says Bush.

Although they offer many advantages, LBDDS also pose many challenges – for the simple reason that they are tricky to get right. “Lipid-based formulations require a lot of expertise and upfront work – and you need knowledge of both formulation and functional excipients,” admits Romanski. “One of the main issues is the variability of lipid excipients. The lipids used in drug formulations are generally derived from natural ingredients, such as palm kernel oil or coconut oil (see box, Sustainable Formulations?), and this is partly why lipid excipients are so well-tolerated – they are, in effect, part of the body’s natural diet. As a consequence, however, the excipients used as raw materials in lipid formulations are inherently variable.”

Sustainable Formulations?

- In many sectors, consumer choice is putting increasing pressure on manufacturers to find sustainable solutions for products and processes.

- n the pharma sector, consumer choice historically has been strictly limited with the patient getting what the physician prescribes, but patients are also becoming more interested in their medicines and their ingredients.

- According to Frank Romanski from BASF, a number of pharmaceutical companies now wish to take sustainable sourcing into account for both over-the-counter and prescription medicines.

- Sustainability is particularly relevant to lipid formulations, since their principal ingredients are derived from natural sources in South East Asia: coconut oil and palm kernel oil.

- The future could see manufacturers under increasing pressure to buy raw lipid ingredients from certified, sustainable sources.

While traditional polymer excipients are usually made to 99 or 99.9 percent purity, the monographs for lipids are notably less specific. The end result is that a given lipid, while remaining within specification, can vary widely according to the manufacturing source, which is why getting lipid formulations to behave predictably in the body requires specific know-how and expertise.

There are a variety of ways in which lipids can be used. At one end of the spectrum, an API may be simply dissolved in a lipid medium such as a long-chain triglyceride oil. The next level of complexity involves the addition of more polar lipids and/or lipophilic surfactants to promote solubilization of the drug inside the capsule and/or its emulsification once released from the capsule into the GI tract. More complex formulations still may be constructed by adding hydrophilic surfactants to this mixture. “Such mixtures promote API solubility in the aqueous environment of the GI tract, thus preventing recrystallization once the capsule is ruptured or disintegrated,” says Romanski. “In addition, they can self-emulsify in the body to form tiny droplets for maximum absorption.” However, it is important to ensure that the drug doesn’t crash out when exposed to the GI tract.

Bush adds that the mixture of lipids in the LBDDS are digested in the body to liberate free fatty acids, or other components of the excipients such as PEG – and these breakdown products themselves can further support product functionality.

According to Bush, the overwhelming majority of LBDDS are presented as softgel or hard gel capsules, which meet industry requirements in terms of commercial scale-up and shelf-life. “In particular, LBDDS pairs very well with softgel technologies,” he explains. “A softgel capsule lends itself to advanced functionalization; for example, more complex LBDDS or different film coatings can be applied to give the capsule targeted release capabilities, such that it only dissolves and releases the API in a given region of the GI tract.”

“Using a capsule also avoids the need to add taste-masking ingredients, which would unnecessarily complicate the formulation process,” adds Romanski. “The softgel capsule is a perfect medium for the oral delivery of a liquid formulation because it protects the API, does not compromise the performance of the fill, permits controlled and targeted delivery, is convenient to manufacture, and is widely acceptable to patients. Combine these advantages with those inherent in LBDDS – solubilization, stabilization, avoidance of first-pass effects – and you have a platform applicable to many ‘difficult’ APIs.”

Softgel Advantages

- Softgel manufacturing can be scaled up to commercial supplies.

- Scale up is relatively straightforward compared with other dosage form manufacturing.

- The softgel has minimal to no interaction with the encapsulated fill.

- The dissolution and biopharmaceutical performance of the fill is not compromised when encapsulated within a softgel.

Back to the future?

What does the next decade hold for oral drug delivery in general and lipid-based formulation in particular? Bush reiterates the evolutionary forces acting on the sector. “The lipid backbones have been in use for many years in the industry, but their functionality and our understanding of how they can be used has changed – and continues to evolve. As the technology becomes more sophisticated, the aims of formulators become correspondingly more ambitious. It is no longer enough just to solubilize a difficult drug in the formulation and keep the drug in solution in-vivo; now the object is to support patient compliance by ensuring the requisite dose is delivered in a convenient number of units. After all, who wants to take six or more tablets, three times a day?”

Bush also adds that the oral delivery of macromolecules using LBDDS is a growing area. Oral formulation of peptides and proteins is well known to be difficult, but it is not impossible. “Increasingly, the industry is moving to embrace the challenges and I think we will see increasing number of oral biologics in the next five to ten years,” he says.

Romanski also agrees that the oral delivery of peptides and proteins will be a hot topic in the coming years. “It would be wonderful to put the new biologics into a solid oral dosage form, and scientific expertise and knowledge is building in this area,” he says. “But I also think that we shouldn’t forget about old drugs. Advances in excipient technology open up the possibility of re-formulating old drugs, previously discarded due to bioavailability issues – perhaps it is a case of back to the future. Clearly, we are nowhere near exhausting the potential applications of LBDDS formulation and exciting times lie ahead for the field!”

- JW Scannell et al., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery, 11, 191-200 (2012).