Painting the Future of Drug Delivery

US Army combat veteran Luis Alvarez has developed a new drug delivery technology that can convert any recombinant protein into a material-binding variant. Here, we find out how the tech can help coat implants and enable long-term local delivery.

From war to drug delivery. Tell us more…

I always loved science and I knew from an early age that I wanted to go into something related to biotech. But when I was younger, I also wanted to serve – and figured that was best while I was still young! My original plan was to serve for around five years and then go off to grad school to begin my second career.

After high school, I went straight into the military academy, where I majored in chemistry and life sciences. Normally, when you graduate from the military academy at West Point, you enter military service, but I was able to obtain the Hertz Foundation Fellowship, which allowed me to spend two years at graduate school. I then went back into regular military service, serving in infantry and cavalry units. While deployed in Baghdad, Iraq, I saw many serious injuries – injuries that would influence my research later down the line. After deployment, I used the remaining years of support from the Hertz Foundation Fellowship to do a PhD at MIT – so I was on active duty the whole time I was studying.

I was fortunate enough to have the flexibility within the military to pursue assignments that were technical in nature; I was able to serve in the Research and Development Command for the US Army, which allowed me to continue with military service while completing three technically connected programs within the biopharma space.

A military career and a scientific career are not a very common combination – and actually I don’t recommend it because of the difficulties of navigating the requirements for each – but it worked out for me.

Luis Alvarez describes the precision targeting of proteins for tissue regeneration to Bill Gates at the 2009 Hertz Foundation Symposium.

How did your experiences in Iraq influence your research?

I noticed that people would suffer serious injuries, mainly to limbs, which doctors would be able to save. Then, many months later, they’d have to be amputated because the limb had deeper tissues (bone, vessels or nerves) that hadn’t healed properly. It seemed strange to me that we hadn’t figured out how to target certain tissues for regenerative repair. So my aim was to develop a technology for the targeted delivery of biologics to enable tissue repair – bone regeneration in particular. And that was the basis of my research in Linda Griffith’s lab at MIT and Richard Lee at Harvard. Linda is a pioneer in tissue engineering, and I was able to learn about the techniques for modifying implants and influencing how the body regenerates. I retired from the military in 2017 to commercialize the technology with Theradaptive.

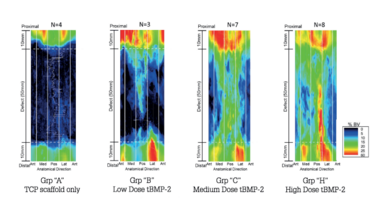

Figure 1. The highest dose of tBMP-2 demonstrates the greatest new bone volume (1).

Could you tell us more about Theradaptive’s platform technology?

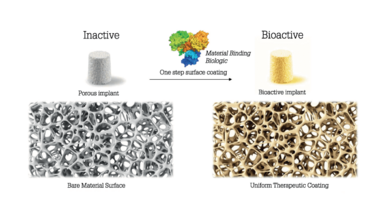

For tissue to regenerate, biological cues must be presented at the right time and place. Though we know what many of the cues are, there has been no way to deliver them to the right tissues and keep them there long enough to have a regenerative effect. In our work we developed a means of modifying proteins via a simple one-step process that doesn’t require chemical modification so that they stick – like paint – to surfaces, such as medical devices. By coating medical devices with bioactive beacons for healing, the body is triggered to surround the implant with regenerating tissue. We made a variant of a protein called bone morphogenetic protein 2. Our variant is called AMP2, and it binds to both permanent and resorbable implants and causes the body to produce bone wherever it is placed in the body. In all studies we have conducted to date we have beaten the standard of care in bone repair and spinal fusion using AMP2 – and we’ve had several meetings with the FDA. We’re hoping to begin the human phase of development within the next year and a half.

What other applications could benefit from your coating technology?

We also have promising results in cartilage repair, with another implant binding protein. The idea is that we might be able to take a “legacy” implant and regenerate the tissue it is working to support. The original idea for the technology was related to traumatic injuries sustained by soldiers, but we now see a great deal of benefit in orthopedic conditions. The projected orthopedic repair market in the US exceeds $15 billion annually, which highlights the need for targeted tissue repair in the general population. But we also believe the technology could improve cell therapy by giving cells long-lasting, local, and highly-concentrated biological stimuli. We’re still a relatively small company, hence our initial focus on trauma and the spine (funded primarily by the Department of Defense and the State of Maryland). We just closed a Series A investment round, which will allow us to expand into additional areas.

Figure 2. Proteins are converted into a material-binding variant via sequence modification.

Figure 3. Materials are coated in one step with with bioactive proteins.

Do you think a career in the military prepared you well for the business world?

Yes, I think so. In business, you have to deal with difficult situations (and people!), for which the military certainly prepares you. I’ve gained a certain amount of resilience to overcome things that at first may seem difficult – or even impossible. For example, if the company is running low on funding or you are facing daunting challenges, persistence and resilience are great assets. The military also teaches you leadership skills – the ability to assemble a team and give them a mission to go after. But I would say that, whatever your background, starting a company is difficult and time consuming, with many unexpected twists and turns. On the other hand, it’s a lot of fun too.

What advice would you give to someone in the military, perhaps with an interest in science, who is thinking about changing careers?

I would say that moving into drug development or biotech can feel intimidating – but it’s a lot like jumping into cold water: it's always scarier before you've done it.

Over the course of my Biomedical Sciences degree it dawned on me that my goal of becoming a scientist didn’t quite mesh with my lack of affinity for lab work. Thinking on my decision to pursue biology rather than English at age 15 – despite an aptitude for the latter – I realized that science writing was a way to combine what I loved with what I was good at.

From there I set out to gather as much freelancing experience as I could, spending 2 years developing scientific content for International Innovation, before completing an MSc in Science Communication. After gaining invaluable experience in supporting the communications efforts of CERN and IN-PART, I joined Texere – where I am focused on producing consistently engaging, cutting-edge and innovative content for our specialist audiences around the world.