Rosalind Franklin, We Salute You

Looking back on the achievements of Rosalind Franklin

Rob Coker | | 4 min read | Historical

A disused laboratory facility in Leamington Spa, UK, made a surprise appearance on real estate property website Rightmove recently, after playing a vital role in the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccinations. Named after the now renowned DNA researcher Rosalind Elsie Franklin, the “megalab” developed some 8.5 million vaccines between June 2021 and January 2022 before being, ironically, cast aside and forgotten. The UK Labour Party’s Member of Parliament for the constituency, Matt Western, took the opportunity to add the listing to the growing number of pandemic-era failures of the government by describing the closure as a “colossal waste” and accusing them of “trying to dispose of it on the quiet.”

It seems unfair that part of Franklin’s legacy is being passed around like a parcel in a parodical echo of her own career, so I wanted to offer a reminder of her substantial achievements.

Born in London in 1920, Franklin grew up in an age when boys and girls were educated separately. After leaving St. Paul’s Girls’ School, she studied physical chemistry at Newnham College, part of the University of Cambridge, graduating in 1941 – wartime! The demand for services to natural sciences was low, so Franklin devoted her energy to the war effort by serving as a London air raid warden, despite being offered a fellowship by the then Chair of Physical Chemistry and later Nobel Prize Laureate Professor Ronald George Wreyford Norrish, whom she found to lack in enthusiasm. In 1942, Franklin abandoned her fellowship to look into the better use of coal, which formed the basis of her doctoral thesis.

The year 1945 brought with it not only the end of World War II, but also a Cambridge doctorate for Franklin. She soon moved to Paris to study X-ray diffraction technology, as she appeared to wish to remain in the geological branch of natural sciences and the lucrative coking industry.

However, in her relentless pursuit of academic and intellectual recognition, Franklin switched to studying the biological sciences in 1950 with a three-year research fellowship at King’s College London. The switch would not only change her own life, but the lives of all who came after.

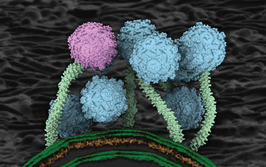

The first step was to design, alongside Raymond Gosling, a “tilting micro camera” with the aim of obtaining greater insights into “the conditions necessary to get an accurate diffraction image of DNA” (1). This development led to Franklin being able to suspend a single DNA fiber, which she exposed to one hundred hours of X-ray. From a pattern on a photographic plate, Franklin was able to analyze and reveal its structure. “Never had X-ray crystallography been put to such deft or momentous use,” states the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. (1)

Being an academic Jewish woman in the mid 20th century came with many non-academic challenges. Perhaps her fellow scientists operated under the assumption that Franklin would be little more than a brilliant assistant, but the culture at King’s College London led biophysicist and fellow Nobel Laureate Maurice Wilkins, who was working on similar research, to share Franklin’s “Photo 51” (developed in collaboration with Gosling) with James Watson and Francis Crick – the three of them going on to win the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Not only does this sequence of events confirm the theory that, behind every great man, there has to be a great woman, it also highlights the struggle faced by women, historically and contemporarily, when it comes to be taken seriously in science. That is not to say that the work of Watson, Crick, and Wilkins did not merit a Nobel Prize, but the work of Franklin and Gosling likewise did not deserve to be overlooked even at that time.

Considered a scientist first and foremost, Franklin, according to former President of the British Society for the History of Science Patricia Fara, would neither dwell upon nor accept the posthumous epithet of “unsung heroine.” Her achievements extend beyond what she did in DNA research, and her technical abilities in conducting research – in various disciplines – remains her major legacy. Fara writes, “She also made foundational contributions to modern understandings of coal, graphite and viruses” (2).

This ability to diversify her interests and areas of research won her the largest award ever allocated to a Birkbeck (University of London) scientist, where she undertook, controversially, research into polio. This research, however, was never completed. Following a fatal ovarian cancer diagnosis in 1956, Franklin died, aged just 37, less than two years later.

Franklin’s posthumous recognitions and legacies are vast – and still growing. Among these, as a small example, are her honorary membership of Iota Sigma Pi (1982); an English Heritage Blue Plaque commemoration (1992); the Royal Society’s Rosalind Franklin Award for outstanding contributors to natural sciences (2003); The Rosalind Franklin Building named in her honor at Nottingham Trent University (2012); the Rosalind Franklin STEM Elementary school in Franklin County, Washington, US (2014); the “Rosalind” space satellite launched by ÑuSat in 2021; and a new bacterial genus, Franklinella, named in her memory (2022).

This diverse, long list of legacies is an apt, ongoing, and fitting testament to the ingenuity and endeavor of Franklin, who has emerged from the traps of history as something more than she was expected to be.

- Dr. Rosalind Franklin, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. Available at: https://bit.ly/3U1H5Yi

- P Fara, “Rosalind Franklin’s Life”, The Rosalind Franklin Institute. Available at: https://bit.ly/3TVMEYg

Following a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature and a Master’s in Creative Writing, I entered the world of publishing as a proofreader, working my way up to editor. The career so far has taken me to some amazing places, and I’m excited to see where I can go with Texere and The Medicine Maker.