Born to Be Manufactured

Tablets are the preferred dosage form for both patients and drug manufacturers; the tableting process is well established and cost-effective, but the science and engineering go deeper than you might expect. A number of aspects must be considered to design a tablet that is well suited for commercial manufacture.

Jim Calvin, Andy Lapinsky |

sponsored by Elizabeth Companies

The manufacturability of an oral solid dose tablet can sometimes be an afterthought, given that most formulation conversations revolve around therapeutic efficacy (dose requirements and tablet format, such as conventional or bilayer tablet), the patient (swallowability and ease of use), and marketing (brand awareness and differentiation). But to make consistently good tablets, early design choices are often more meaningful than choosing good tooling and machinery. Different tablet designs require different engineering considerations and there are many factors that dictate how well a formulation will run in a given tablet press, and if the design a company has in mind for their product is actually practical from a manufacturing perspective. Certain designs used with the wrong punch, for example, create stresses that lead punches to wear out quickly, or result in tablet defects. Choosing in incompatible steel to the formulation compound being compressed can lead to abrasion of tool faces and die walls.

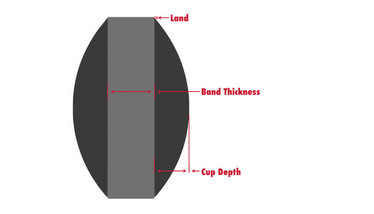

Tablets come in a very wide range of geometrical formations. There will always be a certain amount of weight that is needed in the tablet and from there you must consider the tablet’s length, width, band thickness and cup depth. If the length and width are chosen incorrectly and the tablet ends up too small, the thickness has to grow to accommodate the necessary weight. This is actually one of the most common mistakes we see; as the tablet thickness grows, manufacturers often run into compression issues, as well as high ejection forces, capping and friability problems. Another common mistake is for companies to produce a small-sized tablet successfully, only to find it is then too small to add desired logos or other identifying text on the tablet surface.

The building blocks of good design

In our tooling design process, we use software to create a solid model to evaluate the stresses and strains that a given tablet shape will create on the punch tip. The computer simulations promote collaboration with product designers and timely iterations when changes to tablet geometries are still possible. This type of software can also be used to transfer an existing product to another geometrical shape through reverse engineering. Broadly speaking, there are a variety of tablet geometry aspects that need to be considered.

- Cup depth. A tablet’s cup depth is the distance from the cup’s lowest point (usually the center point of the tablet) to its highest point of the land. Some tablets will have a shallow depth and others will be concave. As the cup depth increases, the compression force that can be used on that tool to achieve tablet hardness decreases. Too much cup height increases the distance for the compression forces to travel from the perimeter of the punch to the apex, or the punch’s cup apex, and can lead to premature punch wear and tear, and even breakage.

- Land. The land is a narrow plain perpendicular to the tablet’s band, creating a junction between the band and cup radius. Although the punch is made out of steel, the area at the perimeter of the tip is very weak so a land should be incorporated into the tablet to strengthen the punch and prevent nicks on the punch edge, which could cause compression issues (see figure 1).

- Band thickness. Too wide of a tablet band can cause high tablet ejection force, and issues with coating and non-uniform density. For all compression tooling, the two closest points are compacted first and this can create a dense area that locks air into the cup, leading to capping issues. If the band is too narrow, it can create high compression forces that may affect tablet hardness, density and cause friability problems, with tablets that are too thin being susceptible to chipping or tablet edge erosion in particular.

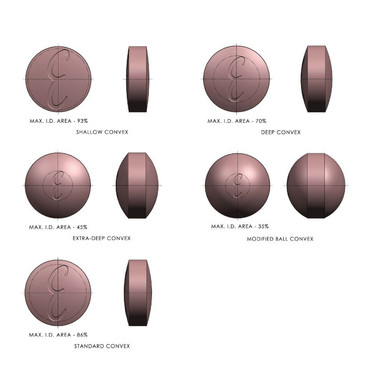

- Identification. The area available for identification on a tablet, such as the addition of a logo, depends on the cup radius and the style of cup, as well as the geometrical shape of the debossing, including the depth and angle needed. The flatter the geometry of the tablet’s cup, the larger the available area for identification. If the debossing is placed too close to the perimeter of the tablet, you’ll lose clarity of the debossing (see figure 2).

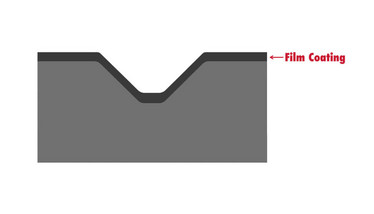

- Film coating. It is important to decide if the tablet will be coated at the very start of the design process because it can affect other aspects, such as debossing. For example, it is important to ensure the debossing is deep and wide enough that the film coating doesn’t fill in the areas and make the identification unreadable. With certain shapes, film coating can also lead to twinning (see figure 3).

In addition to considering the tablet’s geometry, we also advise paying careful attention to granulation. Where possible, try to ensure you have free-flowing granules that aren’t abrasive – otherwise you’ll be wearing down the tooling. Maintenance is important too – take care of your tools! Your operators need to understand how to set-up the machine and identify irregular operation. Once something starts wearing it needs to be addressed before there is a domino effect on other parts of the process.

The early bird

There are many aspects to good tablet design and it’s fair to say that it is a very unique science. You need to understand your formulation, additional components, such as binders and other excipients, and your tools and machinery, especially when considering more complex layer tablets or core-tablets. Chemists and engineers should work together to answer the questions and ensure the final formulation will suit both sides. It is also important to consider the differences between the R&D phase – where you’ll be working at low speeds and volumes – and the production phase where the pressures on the system may be different and possibly more challenging to maintain tablet quality at increased production volumes.

Many in the industry advise drug developers to consider their formulation strategy and impact upon manufacturing as early as possible. We also urge companies to give early thought to manufacturing process to avoid common issues such as picking, sticking, flashing, and high compaction and ejection forces (tips available at https://catalog.eliz.com/toolingtroubleshooting/). There are some “tricks of the trade” that can help compensate for bad tablet design and formulation, such as altering the press feeder speed to affect the hardness and weight of the tablet, but overall it is difficult to effect major change. In the case of multi-layer tablets, tooling design decisions complimentary to tablet press configuration are essential to robust layer definition. Regulatory authorities are strict and once performance qualification has been completed and the line is validated there isn’t much that operators can do. Instead, it pays to get it right early on by considering the options before your design causes manufacturing issues.

Meet the Experts

Andy Lapinsky has been working for Elizabeth Carbide since 1989, taking on roles of increasing responsibility over the years. Today, he is the manager of engineering and CNC programming where he oversees the design of compression tooling and technical services for Elizabeth tooling customers.

Jim Calvin joined Elizabeth in the 1980s making tooling. Early in his career, Jim transitioned to Elizabeth-Hata International (press division) designing and building press control systems, working as a service technician and service manager, servicing and installing equipment, validating, troubleshooting and training. Today, he is General Manager of Elizabeth-Hata International.