Making Small Biotech Work

Innovation is increasingly coming from small biotechs, but such companies rely on external funding to develop the compounds. A solid regulatory strategy is essential to convince investors to fund the further development.

Historically, it’s been the large pharmaceutical companies who have been able to bring treatments to the market but in the 1990s, industry started to see a rise in the number of marketing authorization applications coming from smaller companies (particularly biotechs). During this era, it was traditional for a company to work alone in taking its compound all the way from research to approval, but this has changed in the past years.

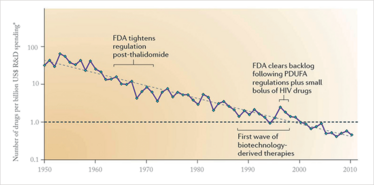

Pipelines have dwindled and drug development costs have risen sharply; in the 1950s, you could put around 50 drugs on the market with $1 billion in R&D spending. Today, $1 billion isn’t enough to get even one drug on the market (1) – see Figure 1. Since 2000, there has been a big increase in the number of industry acquisitions, licensing deals and other commercial partnerships. Big pharma companies still have their own internally generated R&D projects, but they are also increasingly relying on innovation from biotech companies – and, in fact, in several pharma companies, a large part of the pipeline consists of compounds that have been acquired from small companies or biotechs.

Figure 1: Overall trend in R&D efficiency (inflation adjusted). Adapted from (1).

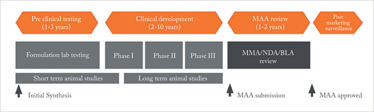

Figure 2: The drug development pathway. Adapted from M. Dickson and J.P. Gagnon, "Key Factors in the Rising Cost of New Drug Discovery and Development," Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 3, 417-429 (2004).

Today’s huge drug development costs mean that it is difficult for small companies to take a drug through to marketing authorization approval without obtaining external funding. Unfortunately, big pharma companies aren’t looking for compounds in preclinical testing; in general, it is expected that the biotech will already have taken the compound through clinical proof of concept – which still involves a lot of work and cost. Biotechs can often get funding for promising compounds through venture capitalists, but again investors prefer to have proof of concept data.

Settling on a strategy

Implementing a regulatory strategy to help ensure that a drug in development meets the final specifications for approval is critical. But given that most small companies have their eyes on obtaining proof of concept and reaching phase II, is a regulatory strategy still needed? The answer is definitely “yes”. With big pharma and investors becoming increasingly cautious – and the biotech world becoming more competitive – small companies need to be more strategic than ever before, and early regulatory due diligence is a must.

Even if a small company is intending to sell a compound rather than taking it to marketing authorization approval personally, they must be able to demonstrate that the compound is as promising as possible to clinch the deal (and to get the best possible price). The same is true if you’re looking for investment – investors want to know that the compound is approvable.

For the inexperienced company (and even the experienced company), developing a regulatory strategy can be riddled with pitfalls. The most important aspect is to remain aware of the long term goals and to have a clear picture of where you want to go with you compound. A target product profile (TPP) is an excellent tool to base yourself on while developing the regulatory strategy of your product. Is your company developing a biotech or chemical product? What is the intended indication? Which indication is best suited to have clear proof of concept? The indication in which you might have the clearest proof of concept data might not be the indication in which you might eventually want to market the product. It is critical to keep the overall goal of the compound in mind; will you be selling your compound after a certain stage in the development, or will you bring the compound to the market yourself?

It is also important to consider the intended market for the drug. For example, if you’re developing a drug for use in the tropic regions, it is key to design your stability program around that. In that case, it is also critical to engage in early discussions with regulators in that region and to pay close attention to local regulations. You should never assume that the North American or European regulations will suit all markets. Thinking about all of this early on will help to optimize your development, as you can decide which regional regulations should be taken into account. In addition, it’s worth looking at whether your compound is eligible for any kind of special status or fast track for approval in your selected market. This can be very beneficial if your compound works in multiple indications – you can pursue the special status for one indication to potentially accelerate time to market (and return on investment). It may not be the ultimate intended indication for your compound, but it is one way to start getting return on investment a little faster – and again could be enticing for investors or buyers.

Speed to market is important, but robust data is critical. Trying to reach phase II as quickly as possible is very tempting, but a well-designed phase I single ascending dose/multiple ascending dose study is fundamental to your clinical development plan. It is critical to have robust safety data at the intended therapeutic dose to efficiently move to the next stages. Insufficient or incomplete phase I data will create concerns with potential investors.

Even getting a drug to phase II can be extremely costly. As described above, it is important to be as thorough as possible in the early stages, but you may find yourself limited by the available budget. In this case, it is necessary to prioritize the essential aspects of your development. In addition, it is useful to engage with regulators early through Scientific Advice in order to de-risk your development program. This gives you a chance to approach potential venture capitalists and partners earlier because you will be able to show that the (non) clinical program has been validated by a regulatory authority.

- J.W. Scannell et al., “Diagnosing the Decline in Pharmaceutical R&D Efficiency,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 11, 191-200 (2012). doi:10.1038/nrd3681

Bruno Speder is Head Clinical Regulatory Affairs & Consultancy at SGS.