The Runaway Outsourcing Train

What can we learn about outsourcing trends from contract manufacturers’ bumpy ride over the last 40 years?

How many contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) are operating in the pharma industry today? There are far too many to name – and outsourcing is now such an important part of pharma manufacturing that it’s hard to imagine a time when there were just a few CMOs. Back in the early days of pharma outsourcing, the role of CMOs was to undertake specialized or hazardous chemistries that pharma companies were unable (or unwilling) to carry out themselves. Tracing the development of the outsourcing sector becomes more difficult the further back in time you go because of the lack of reliable data points, but learning about the history of the industry is always a fascinating exercise. Reflecting on the success stories – and mistakes – of the past can be very useful in guiding decisions about the future. To this end, my colleagues and I have been studying the changes in supply and demand in outsourcing of small-molecule drug manufacturing that have occurred since the 1970s (1).

Unraveling the winding track

After World War II, there was flurry of activity in drug discovery, including antibiotics, antihypertensives and oral contraceptives. As for contract manufacturing, this began to take off in the mid-1970s, with the emergence of blockbuster drugs and big profits. Some of the earliest blockbusters to involve outsourcing were Tagamet (cimetidine) and Zantac (ranidine), which both needed difficult sulfur chemistry. Ranidine was an unexpected success; initial forecasts of 10 metric tons quickly jumped to 900 metric tons. Demand also outstripped supply for a number of antibiotics.

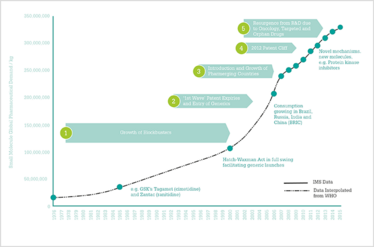

It was a booming time for the industry and demand for extra capacity and services continued to grow until the mid-90s, boosted by the Hatch-Waxman Act and the consequent rise in consumption of generic products as prices eroded. Further expansion in outsourcing followed as the BRIC countries – Brazil, Russia, India and China – emerged as growing consumers for prescription drugs. In the last decade, demand for the manufacture of small-molecule drugs has continued to increase – the result of patent expiries and a surge in new drug launches. Figure 1 shows the rise in demand for small molecule manufacture from less than 25,000,000 kg in 1976 to well over 300,000,000 kg in 2015 – an increase of more than 1100 percent.

Figure 1. Volume demand for small-molecule prescription pharmaceuticals (API).

The number of approvals of new chemical entities (NCEs) in the US adds to the demand picture. In the 1970s and 1980s, the number of launches ran anywhere from 10 to 30 new drugs per year, speeding up towards the launch of blockbusters in 1990s. There was a peak in 1996/97, which was attributable to administration issues, followed by a notable decline in the early years of the new century, as a result of cost-cutting among big pharma and a switch to more complex modalities, such as recombinant proteins and monoclonal antibodies. Approvals picked up again in the mid-2000s because of greater demand for orphan therapies and the introduction of expedited approval processes in the US.

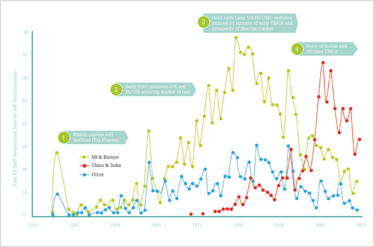

The first crop of truly pioneering CMOs – as opposed to extensions of big pharma manufacturing sites – appeared in the UK, Europe and the US in the 1960s and 70s, and then from the 1980s to 2000, there was an upsurge in CMO entrants in the US and Europe, largely made up of generic API manufacturers and those eager to join in what they perceived as a lucrative market. The upsurge was followed by the entry of large numbers of new CMOs from India and China from 2000 to 2010. Figure 2 shows just how the number of CMO entrants has changed since the 1930s.

Early growth to gold rush

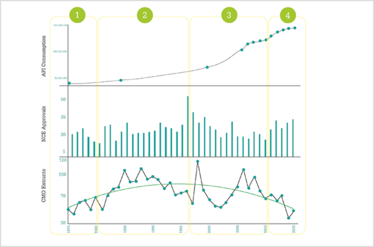

As part of our research, we spoke to a number of industry experts, together representing cumulative experience in the sector of more than 330 years. Essentially, there have been four distinct phases in the CMO industry.

Figure 2. Entrance of API manufacturers by region.

Figure 3. A supply and demand model highlighting four distinct stages of activity. The numbers of CMO entrants (supply side) is shown in comparison to the NCE approvals and pharmaceutical drug consumption data (demand side).

In the early years (pre-1975 to 1980), CMOs were very much technical specialists, often manufacturing intermediates rather than APIs. One of the experts we spoke to explained, “Outsourcing to CMOs was often driven by the need to handle dangerous or difficult chemistries, such as sulfur chemistry, brominations or phosgenations. The early CMOs had often developed these specialties outside of the pharma industry. Large pharmaceutical companies did not want to handle the Safety, Health and Environment (SHE) risk of such chemistry at their large, expensive manufacturing plants, so it led to the use of off-site suppliers. Typically, this would be for a single chemical step, often for an intermediate in the process and often many steps away from the final API.”

From 1980 until 1996, there was then something of a “gold rush” in the market – the growth years – fueled by a shortage of capacity in the booming pharma industry. Large R&D budgets and expectations of a rapid growth in NCE approvals led to the birth of strategic outsourcing, characterized by bidding wars, and a race to the top for NCE launches. Many CMOs became involved in multiple-step synthesis and some even started producing their own APIs. Meanwhile, quality audits were relatively lax compared to today’s standards, which further boosted entries into the sector. Here are some interesting comments from the experts we spoke to about this era:

- “Despite the fact that CMOs were recognized as technology specialists, they previously only focused on a single chemical step before sending the molecule back to the pharmaceutical customer for additional chemistry to the API. This era was the start of multi-step synthesis in CMOs and, before long, a handful of companies were adopting the same business model.”

- “The large barriers to entry – such as access to capital, know-how and engineers – meant that in the early days only a handful of CMOs could offer this. However, as the lucrativeness of the approach became obvious to all, the floodgates soon opened.”

- “Pharmaceutical CEOs were embroiled in a heated battle and a race to out-bid each other, bidding up the number of NCEs they were forecasting launches per year. This created a feeding frenzy for the industry. Analysts were giving super high valuations for pharmaceutical companies as well as predicting a boom period for CMOs. Some banks and analysts even authored reports claiming that the CMO market could expect 15 to 20 percent growth for the next decade based on the success of R&D in pharmaceutical companies.”

About the Study

Research phase

- 500-600 hours of research to decide which data to discount (e.g., due to poor value)

- Mining of data from 20 existing databases (commercial and in-house)

- Refine in focus to data that could help explain supply and demand elements of the industry, without excessive ambiguity

Data sources

- Cambrex

- QuintilesIMS

- Peter Pollak

- FDA

- Jan Ramakers Fine chemical consulting Group

- Newport (Thomson Reuters)

- World Health Organization

- Nice Insight

Experts spoken to

- Simon Edwards, VP, Global sales & Marketing, Cambrex

- Kent Kent, Senior Director, Chemical Manufacturing, Gilead

- Paolo Russolo, President, Cambrex Profarmaco Milano

- Peter Lyford, Commodity Director, GlaxoSmithKline

- Carl Johansson, Global Director, Proprietary Products, Cambrex

- Dix Weaver, Consultant, Weavchem LLC

- Jan Ramakers, Consultant, FCCG

- Rob Miotke, Consultant, Advantage Pharma Solutions LLC

- Jim Miller, president, PharmSource

- Steven Cray, Director, Supplier Relationship Management, Shire

Special mention

Dr Peter Pollak

Dr Pollak was recognized as one of the pioneers of the pharmaceutical fine chemistry industry. He was active in the industry from 1968 until 2016.

1996 to 2010 saw a highly competitive period in the industry. Expiration of patents led to price erosion and growth in generics. Consolidation in the industry resulted in rationalization and cost-cutting as a result of loss of exclusivity. And some pharma companies took the calculated gamble of choosing price over quality, with many CMOs in the US and Europe losing business to India and China. There was a shift away from custom synthesis to toll manufacturing, and the ingenuity and expertise of the CMO was taken out of the equation, making price the only point of differentiation. It’s fair to say that many western CMOs were not prepared for the rapid change in business and found it hard to compete. Experts told us:

- “The entrance of China and India into the CMO industry was largely facilitated by the need for these companies to supply domestic manufacturing for their own drug industries. The majority of them had drug products launched in their local markets and used their captive manufacturing assets to supply APIs into these generic brands. When they faced excess capacity due to peaks and troughs in drug product demand, they turned their captive manufacturing towards the open market and offered API manufacturing on a CMO basis.”

- “The effect of this increase in competition from low-cost countries such as India and China led to differentiation based purely on price. And the Indian companies had the advantage that they were keeping their plants at a base load of capacity with generics when needed. Whether it was this, or the lower expectation on return on capital or lower labor costs, or a combination, it soon became difficult for western suppliers to compete when Big Pharma just went on the hunt for lower prices. As a result, pharmaceutical companies would often adopt a dual continent sourcing strategy between western and eastern CMOs, whilst being aggressive on low pricing.”

- “A handful of big pharma companies led the way during the 2000s in the ‘race to the bottom’ where they were looking to make cost savings from their supply base (to help fund recent M&As). Whilst quality was not considered equal amongst CMOs, they were willing to take a risk on the API quality if it led to a 20 to 30 percent reduction in price. From a political standpoint, it was easier to focus on the short-term corporate cost-saving targets then to worry about the longer-term issues of quality (and the ultimate problems in the supply chain it would and did create).”

- “Given that the API makes up a small fraction of the total product cost – did it really make a difference? No, not really! It only affected certain mature products where the API and the tablet costs were a bigger fraction of the price, such as large volume CV products. However, on NCEs and respiratory products, achieving a lower API cost did not make a big difference at all. We knew this and the company knew this, but everyone was geared up to a ‘sheep dip’ approach where everyone had to be seen to be achieving cost savings whether it made a difference or not.”

Today’s outlook

Some western CMOs went out of business in this time. Others battened down the hatches or adopted new business strategies. Fortunately, since 2010, things have started to look up for western CMOs, with the sector enjoying what I like to call the “resurgent years”. The increasing availability and access of medicines to patients, as well as large numbers of patent expirations, have ensured a steady increase in drug consumption, accompanied by rising NCE approvals. At the same time, rising labor costs in China and India have made outsourcing to these countries less attractive, and some sourcing decisions are now being unpicked and work repatriated to the US and Europe. Pharmaceutical companies are now divesting and closing some mature API plants, and with the number of new entrants to the CMO market falling, there is high demand in the US and Europe for outsourcing partners with the right capacity. Because the market is still heavily fragmented, many of the high quality CMOs have filled their capacity and there are substantial lead times for new projects. Experts said:

- “Some smart thinking Western-based CMOs have kept pace with changing customer demands and requirements, whether this is based on changing product forecasts or a required flexibility from manufacturing scale and assets. Having a finger on the pulse from a market intelligence – ‘what’s next’ – perspective allows them to be ahead of the curve.”

- “Whilst from a technology and capability perspective, there is not much differentiation between Western and Indian/Chinese CMOs – they all have a similar expertize in chemistry, such as high potency, similar plants, similar assets, etc. – there is a big difference in management and leadership style. Western CMOs typically have stronger management teams and people who can adapt to customer requirements and be less rigid to work with.”

- “During the previous decade, many procurement teams had made poor sourcing decisions in the use of Indian and Chinese CMOs. They had outsourced the wrong molecules to the wrong CMOs and created problems in the supply chain. Presumably this was during the ‘race to the bottom’ period.”

- “A lot more of the US and EU-based CMOs are now full when compared to the period pre-2010. The market is a lot tighter for high-quality CMOs. For these CMOs, there is no capacity available before 6 months. Even after 6 months, only 10 percent have available capacity. That said, despite the resurgence, some have accumulated a high debt-to-EBITDA ratio, which they need to service/pay off. This is a worry to any customer using them given the possibility of cash-flow issues or even insolvency.”

We can learn a lot from history; reflecting on the successes and mistakes of the past can help guide us in the future. So what comes next for the CMO sector? In the June issue of The Medicine Maker, I’ll be looking at how the trends of the past 40 years are influencing current developments in the industry and what trends we can expect in the lead up to 2020. As a preview, here are some of the trends we expect:

- Increasing consumption – the trend towards smaller volumes of API manufacture will by offset by the trend for more people to continue to take more medicine.

- Steady innovation – chemistry and small molecules will continue to be the backbone of the pharma industry.

- Dynamic CMO space – CMOs will continue to evolve. We will also continue to see shake-out of under-performing CMOs, as well as sustained merger and acquisition activity.

Matthew Moorcroft is Vice President at Cambrex, New Jersey, US.

- Cambrex, “A History of the API & Intermediates Contract Manufacturing Industry (1975 – 2015),” (2016). Available at: bit.ly/2qjjQe1. Last accessed May 15, 2017.

Matthew Moorcroft is Vice President at Cambrex, New Jersey, US.