Advanced Therapies: The Price is Right?

Health technology assessments find that many cell and gene therapies are more cost effective than existing treatments and managing symptoms with palliative care. But are healthcare systems and manufacturers ready to embrace evidence-based pricing to lessen the impact of upfront costs?

What models do you use to assess cell and gene therapies in terms of their effectiveness and how this relates to pricing?

There really isn’t a uniform model that can be used to assess the potential long-term cost effectiveness of cell and gene therapies because the data available differ in terms of robustness, the intended action, and how that relates to increases in life expectancy and quality of life. But I can give a few examples.

Some of the higher profile assessments we did at the US Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) – where I worked for over ten years – related to use of CAR-T therapy for a couple of different cancers: acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in adults. The modeling was straightforward on the whole because the ultimate goal of any cancer therapy is survival. The challenge in this instance was that the data were new, so there’s wasn’t much follow up on the patient populations in the trials and we had to extrapolate what survival would look like over time. The models we worked with used different survival assumptions to see how the results of the modeling changed. Another challenge was that, like other cancer therapies tested in patients with few other treatment options (“last-line”), the trials had no comparator. In actual practice, however, clinicians will still likely try something, so we had to bring in data from other trials for comparison purposes.

This is quite different to some of the models that were done for cell and gene therapies in rare conditions, where the impact on quality of life was the main consideration. The first approved pure gene therapy in the US was for an inherited form of blindness in children. The challenge was that the primary outcome was new – the ability to navigate a low-light obstacle course. There wasn’t an obvious connection to how that would improve quality of life as measured using standard instruments. The modelers had to make a variety of assumptions about how long the benefit would last and what the quality of life improvement would look like. In the end, we ended up with a range of results where we put boundaries around what cost effectiveness might look like moving forward.

The inherent trade-off is that because these therapies are of such great clinical interest, regulators want to get them to market as quickly as possible. But that means there isn’t a lot of evidence for assessors to work with. That poses a challenge for the modeling, but we’ve done the best we can to try and understand, within reasonable boundaries, what the results might look like over the long term – recognizing that we should be tracking and monitoring to see if our models are reasonably accurate.

How does an assessor take into consideration the benefit of a curative therapy balanced against the huge price tag?

Assessing the cost effectiveness of a curative treatment is difficult because there aren’t yet good methods for understanding the “value of a cure.” But methodologists around the world are starting to think about it more carefully with these potentially curative therapies becoming a reality. The approach we took with CAR-T is a sensible way to examine the problem. This would mean if survival reaches a certain stasis point, then we would consider that to follow the survival trend of the general population. This makes recognizing the value of a cure relatively straightforward, but the question of how to reimburse a curative therapy within systems that are set up to reimburse chronic therapies is an entirely different one.

Do healthcare assessments generally say cell and gene therapies are value for money?

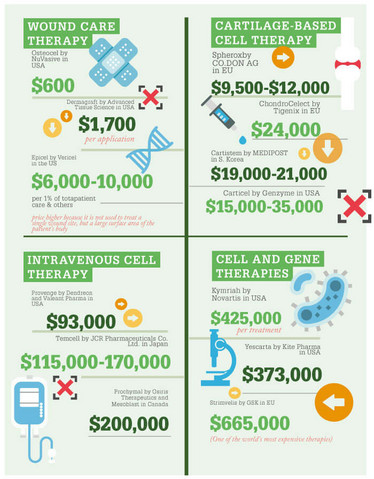

The results of our modeling in CAR-T, at least for these two initial cancers, make a relatively compelling case for the cost effectiveness of CAR-T. We found that they were cost effective relative to standard chemotherapy. However, you might say that standard treatments are already expensive, so this is a false comparison. However, we also found that the CAR-Ts were cost effective in comparison to palliative care – in other words, no active chemotherapy and simply managing the patient’s symptoms. This is a very strong case for paying for CAR-Ts, but the problem that remains for health systems is paying the high upfront costs...

Will cell therapies require different payment or reimbursement schemes?

The short answer is, yes! There are some interesting reimbursement schemes that are being discussed and/or put in place to try to tie reimbursement to whether a durable response and/or cure is actually achieved. I was part of a multi-stakeholder discussion in Canada on CAR-T cell therapies around requiring manufacturers to report quarterly updates on survival, so that payment could be adjusted based on response.

In the US, one of the manufacturers of a CAR-T said that payers and hospitals would not be charged if the patient was not able to receive an infusion – in other words, if there’s some sort of manufacturing failure. They also said that there would be no charge if the patient did not exhibit a response by one month following treatment. There’s been a lot of debate about whether one month is an appropriate time point, given that we’re interested in a durable response, and discussions will continue. Overall, I do think some sort of outcomes-based contracting or managed entry scheme will be required because the cost is exorbitantly high upfront.

Is there a global consensus across different countries in how to assess these products?

There hasn’t been a large number of assessments at this point, but there are some different approaches, depending on the country, particularly when dealing with high-cost therapies for very rare conditions. The challenge there is that not only do you have a relatively small evidence base because the therapy is on an accelerated pathway with the regulator, but you also have very small patient numbers and, in some cases, outcomes measures that aren’t standard.

The Canadian approach isn’t to try to understand the cost effectiveness, it’s more about understanding the potential budgetary impact to the provincial systems and what the long-term outcomes might be. As Nick discussed, NICE in the UK will consider a higher cost effectiveness threshold for ultra-rare conditions. Although ICER does not change their threshold, they do report additional higher cost-effectiveness thresholds when the condition is ultra-rare with consequently small patient numbers.

What difference does the type of healthcare system make?

There are vast differences between a decentralized system like the US and others. For example, in the US there are certified treatment centers for specialized areas of care, and for cell and gene therapies we will need to create some sort of network of centers of excellence to refer patients to. In single payer system like the UK, there’s the ability for that system to identify where those centers will be and how patients will be allocated to them. In the US, identification has really been up to the manufacturers, and there is greater scope for a national commercial payer to match up to those centers of excellence than for small regional payers. The additional expense for a small regional payer who may not have any centers of excellence near them to refer patients to across the country is a big challenge.

Do you expect to see a greater number of different schemes as more products are approved and for different indications?

Yes, especially in the US where the payer has to react to the price, as there’s no real ability to start out with an agreed upon price like there would be with a formal HTA. In the US, there has been some discussion around the possibility of the price itself being adjusted depending on new evidence. At a public meeting, I pitched the idea to the manufacturers that perhaps they come out with a lower price at launch, based on the evidence available at the time of regulatory approval. But then as evidence accumulates, the price can go up or down depending on how well the therapy is working. I got an expected response: companies thought the approach would pose too much risk. But at the same time, at least in the US, the challenge is that the start-price is often nowhere near close to what anybody would consider good value for money, despite what economist might say. So we need to agree something on outcomes-based contracting to get a little bit closer to a reasonable price.