Rewriting the Rulebook

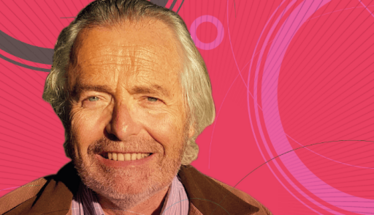

Sitting Down With… Frédéric Triebel, Co-Founder, Chief Scientific Officer and Chief Medical Officer of Immutep, France

Did you always want to be a molecular biologist?

I wanted to be a doctor when I was young, and I went to medical school when I was 16. I enjoyed the holistic view of science I received there – physics, chemistry, a bit of mathematics and statistics, as well as anatomy and physiology – and I certainly learned a lot. But working in a hospital essentially involves applying the rules you have learned. Though that is rewarding, I was more fascinated by the prospect of discovering new rules. We’ve known since the ancient Greeks that regardless of how much knowledge you have, there’s always an ocean of the unknown. So I decided to put down the textbook and turn to the microscope.

What did you work on initially?

I started off in haematology in the 1970s, but switched to immunology – my thesis was on human T cell cloning. I then worked on sequencing human T cell receptors, which was new for the molecular biology field. At the same time, I was also working on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes – trying to see what kinds of T cells there were and why there are so many T cells in some human tumors. There were a lot of parallels with an autoimmune disease, which was a good sign if you’re interested in cancer immunotherapy. We didn’t know at that time why these T cells were not doing their jobs and killing the tumors. It’s been fascinating to watch the gaps being filled in over the decades leading to the development of CAR T cell therapy and other immuno-oncology treatments we see today.

You are perhaps best known for discovering LAG-3. How did that come about?

I was at the University of Strasbourg for my second post doc using a new and sophisticated molecular biology technique that allowed us to clone new mRNA expressed specifically in activated T cells. And so, 30 years ago, I ended up discovering the lymphocyte activation genes, LAG-1, LAG-2 and LAG-3 – the latter proving to be an important checkpoint molecule for the immune response. But we also realized that there was a relationship with another molecule: CD4. We saw that they sat together on human chromosome 12 and thought that they might share the same ligand. A few years later, we were able to show that the LAG-3 protein was a ligand for MHC Class II molecules like the co-stimulatory CD4 molecule, and that LAG-3 function in the T cell was co-inhibitory. These molecules function like Yin and Yang – a balance between co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory activity, where a lack of harmony leads to problems like autoimmune diseases.

How has the checkpoint inhibitor field developed since your discovery of LAG-3?

Just look at the numbers. Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was registered by Merck in 2014 for melanoma – a small market – and it is a blockbuster, used in more than 22 indications. It’s even replacing chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for lung cancer. But despite this success, if you look at metastatic carcinomas on the whole, the outlook for patients is bleak. These diseases are currently incurable and there have been few advances in treatment since the 1980s. I believe that we’re on the cusp of something significant with more therapies aimed at treating a patient’s immune system to enable the body to effectively fight cancer – in combination with other drugs. But the potential of the field extends to other indications too beyond cancer and auto-immune diseases. Consider how T cells attack endothelial cells and create the chronic inflammation we see in atheromatous patients, or the role brain inflammation plays in Alzheimer’s disease.

How did you find the transition from research to industry?

Co-founding Immutep was not such a huge upheaval; I always wore many hats during my research career. For example, I was a professor of immunology teaching students, a clinician treating patients, and a biologist conducting research, but I was also helping to set up early stage clinical studies. I also worked with companies on cancer vaccines and observed how our industrial partners worked. I think this stood me in good stead to deal with a variety of different challenges in industry: be it manufacturing, budgets, regulation or investors. One thing I never tried to do is reinvent the wheel; I found a good, experienced partner – John Hawken – to help launch the company.

Have you faced any major hurdles during your career?

Many! You may go to a company’s website and see that everything looks great, but behind the window dressing you’ll always find challenges. A huge one is convincing investors to put their money behind an unproven and potentially risky approach. Again, basic research – where you’re competing to be the first to publish – was good training. There, I learned resilience as many research projects fail. Just look at LAG-1 and LAG-2: we didn’t end up with anything significant with those, but we decided to continue with LAG-3 because of the central importance of its ligand, MHC class II, in immunology. Finding LAG-3 was rather serendipitous, but I had to be confident that it would be worth working on for years – possibly decades. Convincing yourself, from the beginning, that something is worth years of your life is surely harder than convincing investors in the future!

Over the course of my Biomedical Sciences degree it dawned on me that my goal of becoming a scientist didn’t quite mesh with my lack of affinity for lab work. Thinking on my decision to pursue biology rather than English at age 15 – despite an aptitude for the latter – I realized that science writing was a way to combine what I loved with what I was good at.

From there I set out to gather as much freelancing experience as I could, spending 2 years developing scientific content for International Innovation, before completing an MSc in Science Communication. After gaining invaluable experience in supporting the communications efforts of CERN and IN-PART, I joined Texere – where I am focused on producing consistently engaging, cutting-edge and innovative content for our specialist audiences around the world.