The Great American Debate

It’s Trump versus Clinton in the US elections race. Who will become the 45th President of the United States of America? And how will the pharma industry be affected?

In the May issue of The Medicine Maker, we dipped our toes into the choppy waters of European politics with our coverage of the United Kingdom’s referendum on EU membership. Now, we direct our attention across the Atlantic to the election that will take place on November 8, 2016.

Many have drawn parallels between the UK’s referendum and US elections. Much like the “Remain” campaign in the EU referendum, Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party nominee, is seen as the safe choice – an establishment figure representing a continuation of the status-quo. Republican Donald Trump, on the other hand, is the renegade, anti-establishment outsider – whose slogan “Make America Great Again” taps into a feeling held by some Americans that their country has lost its way. Clinton has swathes of endorsements from business leaders, newspapers and academics, to musicians, actors and comedians (1), as well as strong support among female, African American and Latino voters, whereas Trump appeals to the so-called “white working-class”, who, like a large chunk of “Leave” voters in the UK, are concerned about the effects of mass immigration and skeptical of the supposed benefits of globalization.

Trump is only slightly behind in The New York Times’ polls (41 percent national polling average vs 43 percent for Clinton) but other statisticians claim the odds are in Clinton’s favor. At the time of writing, for example, the pollster and statistician Nate Silver gave Hillary a 67 percent chance of winning (2). But the UK’s shock “Brexit” vote has taught us that polling stats can’t always be relied on. Just six hours before the final result in the UK’s EU referendum, the bookmakers were giving “Leave” a mere 10 percent chance of winning. We all know how that panned out in the end. Trump himself seems confident of a win – recently tweeting that people will soon be calling him “Mr. Brexit”.

With over a month still to go and the presidential debates yet to take place, anything can happen, and our crystal ball is once again shrouded in mist. But whatever the result of the election, there are likely to be some big changes to the pharma industry, particularly when it comes to drug pricing.

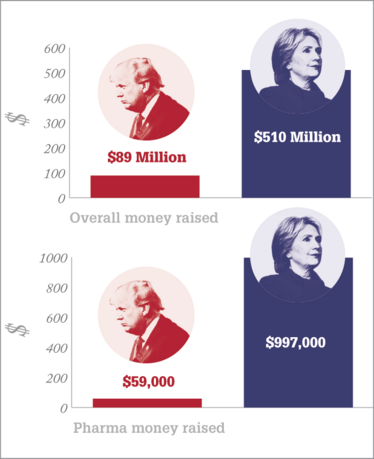

Which side is pharma backing?

How have the Top 9 pharma companies spent their money?

Novaris: $1450 (Trump) $28,290 (Clinton)

Pfizer: $2100 (Trump) $115,091 (Clinton)

Roche: $4572 (Trump) $73,005 (Clinton)

Sanofi: $1,086 (Trump) $24,889 (Clinton)

Merck & Co.: $950 (Trump) $28,620 (Clinton)

Johnson & Johnson: $2,329 (Trump) $72,236 (Clinton)

GSK: $145 (Trump) $12,010 (Clinton)

AstraZeneca: $627 (Trump) $13,144 (Clinton)

Gilead Sciences: $1,350 (Trump) $34,344 (Clinton)

Data obtained from www.opensecrets.org

Pharma feels the winds of change

Unlike the presidential election, in the British referendum only one side of the debate guaranteed change; trade, regulation and investment in the pharma industry could all be affected by Britain’s vote to leave the EU,, but a Remain vote would have most likely meant business as usual for companies. In the US election, there is a strong possibility that regardless of who becomes the next President, changes with stark implications for companies in the pharmaceutical sector are almost guaranteed.

Drug pricing controversies, fueled by the Turing Pharmaceuticals situation last year and Mylan’s recent decision to raise the price of the EpiPen, have brought to the fore concerns that many Americans have with the cost of medicines. One poll found that 72 percent of Americans think that the cost of prescription drugs is unreasonable, with 74 percent thinking that drug companies put profits before people (3). “Companies often complain, saying ‘it’s just the media picking on us’,” says George Sillup, Chair and Associate Professor of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing at Saint Joseph’s University, US. “But more often than not, it’s an imprudent price that attracts media attention.”

Both candidates view the rising cost of medicines and the recent price-gouging activities of certain companies as something that must be combated, which led Novartis CEO, Joe Jimenez, to tell the Financial Times, “We believe that, no matter which candidate wins, we will see a more difficult pricing environment in the US.” (4)

In the aftermath of the Turing controversy, Trump, though light on policy proposals, was quick to denounce the company’s infamous CEO Martin Shkreli, calling him a “brat” and describing the price hike as “a disgrace”. Clinton, meanwhile, has released three specific policies in direct response to the EpiPen price hike, which include: making alternatives available and increasing competition; penalties for unjustified price increases; and emergency importation of alternative treatments. These policies are in addition to Clinton’s broad plan for reducing the cost of drugs, which includes changes to the healthcare landscape that she has been advocating for the best part of two decades.

Medicare negotiations – a hard sell

Clinton has a long history of opposition to rising prices in the pharma industry. In 1993, shortly after Bill Clinton became President, Hillary was made Chair of the President’s Task Force on Health Care Reform. In the fall of that year, The Health Security Act of 1993 was introduced in Congress. Under Title 1, Section 1572 of the bill, Hillary Clinton’s team wanted the FDA to make “cost” a central consideration when evaluating whether or not a drug would be fit for market – a proposal that raised eyebrows in pharma circles at the time (5). The bill collapsed, but Clinton remained steadfast in her opposition to rising drug prices.

During her unsuccessful bid to become the Democrat Nominee for the presidency in 2008, Clinton again argued for reforms to curb the cost of prescription drug prices, this time advocating Medicare price negotiations. Medicare is a national social insurance program, mainly for the over 65s, and Part D of that program subsidizes the costs of prescription drugs and prescription drug insurance premiums for Medicare beneficiaries. Clinton proposed repealing the “non-interference” clause, which prohibits the Secretary of Health and Human Services from interfering in the private price negotiations between Medicare Part D plans and drug manufacturers. Again, the plan failed to come to fruition when the Obama administration opted to keep the non-inference clause. In her team’s own words, “She’s been committed to this fight throughout her career, and is continuing it today” (6).

Since Clinton won the Democratic nomination, she has again argued for Medicare price negotiations in her plan to reduce drug prices. Moreover, Trump has broken party line by publically stating that Medicare could “save $300 billion” a year if it negotiated discounts (unlikely, considering Medicare’s total spend on drugs is around $78 billion). “We don’t do it. Why? Because of the drug companies,” he told a crowd in New Hampshire earlier this year (7). However, whether Trump would push to repeal the non-interference clause is unclear, as he (unlike Clinton) did not include the policy in his list of healthcare reforms (8).

Curbing the Cost of Medicines

We asked four experts how they would keep the cost of prescription drugs under control.

We asked four experts how they would keep the cost of prescription drugs under control.

Patricia Danzon, University of Pennsylvania

I am mainly concerned about the way drugs are reimbursed. The current system means that there is no limit on prices at launch or on price increases, resulting in continuously higher launch and post-launch prices, which of course leads to higher costs for payers and consumers.

I would like to see a more structured value-based approach that sets limits on reimbursement, and to see payers given the ability to negotiate prices based on some notion of value creation in terms of the health outcomes delivered. This could be similar to NICE in the UK, which looks at the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) and cost savings delivered by a new drug.

Fiona Scott-Morton, Yale University

The way that we get price concessions in the US today is the process of creating a formulary and omitting drugs from that formulary, or giving them preferential placements. So a tier 1 drug has a co-payment of $20 and a tier 2 drug has a co-payment of $50, which encourages the consumer to buy the one on tier 1. In Medicare Part D, the government says the formulary must include all the drugs in the six protected classes – this means insurance companies must buy all of them, limiting their ability to bargain for low prices. I think we should loosen these restrictions so that pharmacy benefit managers can create substitutes and thus bring down prices.

Robert Zirkelbach, PhRMA

Patients in the US are being asked by insurers to pay more towards the cost of their medicines than ever before with ever-higher deductibles. When we talk about the costs of treatments, we also need to discuss the cost of healthcare coverage and ensure that patients have adequate insurance.

There are things that can be done to address the cost concerns that people have raised. One is to continue to spur competition in the marketplace, but another is to modernize the FDA so that regulators have the tools to evaluate 21st century medicines. Science is evolving to a point where it can now accomplish what was previously believed to be impossible and we need to ensure that regulators have access to the right tools to understand and evaluate new medicines and technologies.

We also need to look at how we pay for medicines. There is a move towards paying for value through a value-based healthcare arrangement. Many of our companies have arrangements with health insurance companies around the world, but there are barriers in the US regulatory system that make it harder to do this. Moves towards loosening these restrictions and allowing the marketplace to experiment with different ways to pay for new medicines will go a long way to addressing the rising cost of medicines for patients.

Dean Baker, Center for Economic and Policy Research

The basic problem is the huge disconnect between drug prices and the cost of production as a result of patent monopolies and other forms of protection. Granting patent monopolies may be a good way to finance research in other areas, but it leads to enormous distortions in the pharma sector that both lead to serious access problems and distort the direction of research.

In terms of access, if we start from the standpoint that drugs could be produced and sold as generics, we see that the problem of access is almost entirely due to the protections granted by the government. Almost all drugs would be relatively cheap in a free market: we create the problem of drugs costing tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars per treatment through patent protection.

I would really like to see the next president experiment with ways to expand the role of public open research. This could mean paying for some clinical trials and the government could even pay for parts of trials with the condition that the patent or data exclusivity doesn’t last long, and that the test results are posted. Alternatively, the government could pay for pediatric trials as an alternative to extending a patent for six months. It would give us a basis for comparing relative costs.

“Medicare is a huge proportion of business for a number of the large pharma companies,” says Sillup, who spent 30 years in the healthcare industry. “This was up for negotiation when Obamacare was being developed.” When Part D was being drafted, pharma actually helped fund the program so that Medicare price negotiations would be ruled out. “From the perspective of a big pharma company, this alone could have a decisive impact on the profitability of your corporation,” says Sillup.

There is also a question of whether the policy would actually work to bring down the cost of medicines at all. Patricia Danzon, Professor of Health Care Management and an expert on drug pricing, argues that it could, but only under one condition. “The policy would have to be combined with some loosening of requirements that Medicare should cover every drug in certain classes,” she says. “When a payer negotiates with drug companies for discounts, what gives them leverage in the negotiations is the ability to either refuse to put the drug on formulary, or to put the drug in the non-preferred position on the formulary – so they essentially have to be willing to walk away if they don’t get a reasonable discount.” For the policy to achieve its aim of negotiating down drug prices, Danzon adds that Medicare must be able to choose selectively between drugs in classes where there are multiple drugs available.

Danzon also argues that Medicare should use the value created by a new drug to assess what they are willing to pay. “I think it would make a lot of sense if Medicare was willing to pay higher prices for drugs that deliver innovative benefits for patients or cost savings for the system, while being able to be more hard-nosed in the negotiation for drugs that don’t deliver much incremental benefit.”

But whether Medicare would be willing to leave drugs off formularies is difficult to gauge. Fiona Scott-Morton, Theodore Nierenberg Professor of Economics at Yale University, argues that Medicare price negotiations suffer from the difficulty in creating a credible threat to leave drugs off formularies. “Let’s say there are three statins and I only need one or two, so companies bid to have their drugs on the formulary and Medicare negotiates a lower price – is Medicare really willing to exclude two statins from the whole of Medicare?” she says. “I don’t think patients would be happy with such an arrangement. If Medicare has to buy all three, it isn’t really a negotiation. But if this isn’t what people mean by ‘negotiation’, then what they are really talking about is the government setting price controls.”

Dean Baker, co-founder of the Center for Economic Policy and Research, produced a report a decade ago pointing out that foreign governments and the Veterans Administration are able to secure prices that are much lower than what consumers pay in the US (9). “We should at least try to reduce drug prices to the levels paid in Canada and Europe,” he says. “This should still leave the industry with plenty of money to fund research.”

Robert Zirkelbach, Senior Vice President of Communications at Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), disagrees. “The current policy is working,” he says. “Having the government set prices, and having the government determine what medicines patients can get access to, is not something that people want – and has been rejected in the past. Insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers (the people who negotiate on their behalf) already negotiate medicine prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers. In fact, that negotiation is so aggressive that the congressional budget office – the ‘scorekeepers’ in Washington – said that allowing Medicare to negotiate prices wouldn’t save any money unless they were willing to limit the medicines patients can get access to.”

If the scheme did go ahead and Medicare was able and willing to leave certain drugs off the formulary, drug manufacturers may be going head-to-head in bidding for the coveted spot on the Medicare formulary – not an appealing prospect for pharma companies. But with the scheme dependent on limiting patient access to drugs, it remains to be seen whether it would be politically viable.

Trumponomics Explained

Trump’s main economic policy is based on redefining the US’s trading relationship with China. Trump has proposed slapping a 45 percent tariff on Chinese imports if China doesn’t stop undercutting US manufacturers through export subsidies, currency manipulation, intellectual property theft and lax worker safety and environmental regulations. He also seeks to punish US companies who have moved jobs offshore with 35 percent tariffs on their goods. His aim is to reduce the enormous $365-billion trade deficit with China and retain US jobs – but would it work?

Most economists warn against perturbing free trade and the free market. But Steve Keen, Professor of Economics at Kingston University, UK, is critical of the prevailing “neoclassical” school of economics. We asked for his thoughts on Trumponomics…

What would Trump’s tariffs mean for US businesses?

For anybody who has production located off-shore, particularly if they’re in China, their costs of exports will increase by 45 percent – which is pretty heavy. At that level of change, companies will have to ask whether it’s worth their while investing in countries that now face a 35 percent tariff for exports back to America. That is the device that Trump wants to use to push American firms back on-shore.

How will Trump’s tariffs impact the US economy as a whole?

I don’t think these tariffs will have the damaging impact that most people are expecting, but the 45 percent tariff on Chinese imports would throw the whole international World Trade Organization system into chaos – making it difficult to implement. One thing that Trump might be able to do is to force American multinationals to relocate production back home – thereby treating it is as a domestic impulse rather than one allying to international production in general.

You expressed support for Bernie Sanders in the primaries – what are your thoughts on Hillary Clinton?

Clinton stands for business as usual – a continuation of what you’ve already seen from the Bush, Bill Clinton and even the Reagan administration before that. Clinton is basically pro globalization. Trump and Sanders are both appealing to working class and middle class Americans, who have seen the guts ripped out of their cities and their industries over the last 30 or 40 years because of globalization. My analogy for globalization is castor oil. Advocates of castor oil used to say “you’re not going to like the taste, but it’s good for you”. The US working class is now saying “we’ve been drinking this globalization castor oil stuff for 40 years. It tastes vile, and it’s been vile for us.”

Is R&D priceless?

In Clinton’s comprehensive “Plan for Lowering Prescription Drug Costs”, she lists a number of policies aimed at getting pharmaceutical companies to spend less on marketing – especially direct-to-consumer advertising – and more on research and development. The document states: “Clinton’s proposal would require pharmaceutical companies that benefit from federal support to invest a sufficient amount of their revenue in R&D, and if they do not meet targets, boost their investment or pay rebates to support basic research.” The document goes on to say that the idea is based on a provision of the Affordable Care Act that required insurance companies to pay rebates to consumers if their profits and administrative costs were an excessive share of benefits actually paid out to consumers. Research suggests that the policy has brought down premiums (10), despite critics claiming that the scheme would reward inefficient spending on medical care.

But a number of policy experts have raised concerns over rewarding pharmaceutical companies for the amount of R&D they carry out, rather than for the value of their products. “The problem under this plan is that everybody and his brother can go and do R&D and come up with rubbish,” says Scott-Morton. “And yet the taxpayers would be paying them anyway. I think it’s much better to pay people based on results.”

Danzon agrees, adding, “I think this creates an incentive for companies not to be cost conscious in their R&D investments.”

Advocates of the policy, however, hope that it will deter companies from “price gouging” by denying companies federal funding if they sell drugs for high prices, having purchased the drug when they are close to market-ready, without having spent money developing the drug themselves. “The policy is misguided, although it aims to address an appropriate concern with price increases that have occurred for older, often off-patent drugs,” says Danzon.

But critics argue that rather than reduce prices, companies would simply pour money into R&D with no guarantee of success. “You really think companies aren’t going to find a way of justifying their expenditures?” asks Charles Rosen, Clinical Professor of Orthopedic Surgery and President of the Association for Medical Ethics. “Companies will find a way of moving things around. I can’t see how this policy could be accomplished.”

Trump: Abolish borders (for drugs)

Trump’s position on the pharmaceutical industry is somewhat less clear than Clinton’s, whose long history of opposition to rising drug costs is well documented. This could explain why, by and large, pharma has spent a lot more on the Clinton campaign (see graphic: Which side is pharma backing?). “I think a lot of people in the pharmaceutical industry are feeling that there’s a greater sense of stability with Hillary Clinton – the devil you know…” says Sillup. “But from the perspective of a pharma CEO, asking ‘what is Donald Trump going to do?’ You just don’t know.”

Much like the “Leave” side of the UK’s EU membership referendum, Trump represents something business dislikes – uncertainty. Unlike Clinton’s long list of reforms to curb the rising cost of prescription medicines, Trump really only has one official policy with direct implications for pharma companies – allowing American consumers to purchase drugs from abroad. This policy is also supported by Clinton, which means that the importation of prescription medicines is likely to be on the agenda regardless of who wins the Presidency.

Baker argues that the policy would cause prices to fall to the level of prices elsewhere in the world. “This would be a great thing in my view, but it would certainly undermine the current patent-monopoly financing model in the pharmaceutical industry.”

Rosen agrees: “Drug companies would hate it, but I think it would be great to import drugs from abroad. Companies make up excuses that it would be dangerous and so forth, but I think importing identical drugs from other counties would be fine and worthwhile.”

However, Danzon and Scott-Morton believe that allowing consumers to buy drugs from abroad would increase prices in those countries, rather than decrease them in the US. “The US is such a dominant market that it really would not make sense for a company to sell at a low price in a much smaller market,” says Danzon.

“Suppose we imported from Canada,” says Scott-Morton, “Canada has a GDP one tenth the size of the US. Let’s say Canada bought a drug for $50 and in the US we pay $100. If the US announced that we are not going to pay $100 anymore and we’re just going to buy the drug from Canada instead, drug manufacturers will simply charge the Canadians $95.” The argument is that companies will be happy to lose some demand in smaller markets like Canada, if they get to keep all of their US demand.

Another concern over the policy is the safety of the drugs being imported. The FDA argues that drugs from abroad could potentially be counterfeit, contaminated or sub-potent, as it is difficult to determine whether they meet FDA standards and have been manufactured in a plant listed on an FDA-approved new drug application (11). However, proponents of drug importation argue that drugs manufactured in Germany or Canada, for example, would be perfectly safe to import.

But Zirkelbach points out, “What a lot of people don’t realize is that the importation of drugs from other countries is already permitted. If the Secretary of Health and Human Services would sign off that the medicine is safe and effective, it can be imported. But no Secretary has been willing to do so because of the safety concerns.”

A tamer forecast?

So regardless of who ends up in the White House, the pharma industry is likely to have to weather change. But one huge caveat is that the President requires the support of the two chambers of congress – the Senate and the House of Representatives – to get their bills passed. Predicting whether or not a politician will carry out their promised election pledges isn’t easy. That said, Clinton, has a long and documented history of opposition to drug prices so we can be pretty sure she will try to follow through with these, but would she be able to get her proposals through the two houses?

“Right now, the polling suggests that if Clinton wins the presidency, the Democrats will probably take back control of the Senate,” says Chris Dale, Director of Public Relations and Communications for Turchette. “But the sticking point is the House of Representatives. Because of the way the districts are drawn up, the Democrats only have around a five percent chance of a majority in the House of Representatives.”

This could result in a gridlock situation where Clinton would find it very difficult to get her proposals though Congress. “But if Trump pulls this off, the Republicans will have complete control,” adds Dale.

If the Republicans have a majority in both chambers of Congress, it could mean the end of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). Trump has argued that, “No person should be required to buy insurance unless he or she wants to.” Initially, what exactly Trump would replace it with was unclear. (Speaking with CNN, Trump said he would replace it with “something terrific” and that he’d “work out some sort of a really smart deal with hospitals across the country” (12)). But in his list of healthcare reforms “to make America great again”, it states that he would allow anyone to deduct the full cost of their health insurance premiums for their income taxes, as well as other policies that he says follow “free market principles”.

If Clinton wins, would she be able to get through the policies that Trump has also advocated? “I suspect that Medicare price negotiations and drug importation will immediately become politically untenable for Republicans because they won’t want to help Hillary Clinton achieve her healthcare objectives,” says Dale. “But if Trump wins, then both of these policies are possible.”

Despite this election being described by some commentators as one of the most divisive in recent years, the two candidates for the presidency are remarkably close on pharma. This has led Ian Read, Pfizer’s CEO, to say that he cannot currently “distinguish between the policies that Donald Trump may support or those that Hillary Clinton may support” (13).

In fact, because the Democrats will find it almost impossible to win a majority in both houses of Congress, the election may throw up a strange situation whereby the US will only see some of Clinton’s pharma-related policies if Trump becomes president...

James Strachan is Associate Editor of The Medicine Maker.

- Wikipedia, “List of Hillary Clinton presidential campaign endorsements”, (2016). Available at: bit.ly/1ODM9tA. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- FiveThirtyEight, “Who will win the presidency?” (2016). Available at: bit.ly/1ODM9tA. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- KFF, “Kaiser health tracking poll: August 2015”, 2015. Available at: kaiserf.am/1UTGMaK. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- Financial Times, “Novartis braced for US price shake-up after presidential election”, (2016). Available at: kaiserf.am/1UTGMaK. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- PharmExec, “Hillary’s History on Rx Price Controls”, (2015). Available at: bit.ly/1PO1sRr. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- Hillary Clinton, “Hillary Clinton’s plan for Lowering Prescription Drug Costs”, (2015). Available at: hrc.io/1Zai488. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- Politico, “Trump backs Medicare negotiating drug prices”, (2016). Available at: hrc.io/1Zai488. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- Donald J Trump, “Healthcare reform to make America great again”, (2016). Available at: bit.ly/1QmPwVj. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- Dean Baker, “The savings from an efficient Medicare prescription drug plan”, (2006). Available at: bit.ly/1QmPwVj. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- KFF, “Beyond rebates: how much are consumers saving from the ACA’s medical loss ratio provision?” (2013). Available at: kaiserf.am/1iUDhDy. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- FDA, “Imported drugs raise safety concerns”, (2016). Available at: bit.ly/2cp03jD. Last accessed September 12, 2016.

- Forbes, “Donald Trump hares Obamacare – so I asked him how he’d replace it”, (2015). Available at: bit.ly/2cAQUtH. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- The Intercept, “Pfizer CEO can’t ‘Distinguish between the policies’ of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton”, (2016). Available at: bit.ly/25MKmsL. Accessed September 5, 2016.

Over the course of my Biomedical Sciences degree it dawned on me that my goal of becoming a scientist didn’t quite mesh with my lack of affinity for lab work. Thinking on my decision to pursue biology rather than English at age 15 – despite an aptitude for the latter – I realized that science writing was a way to combine what I loved with what I was good at.

From there I set out to gather as much freelancing experience as I could, spending 2 years developing scientific content for International Innovation, before completing an MSc in Science Communication. After gaining invaluable experience in supporting the communications efforts of CERN and IN-PART, I joined Texere – where I am focused on producing consistently engaging, cutting-edge and innovative content for our specialist audiences around the world.