Addiction by Prescription

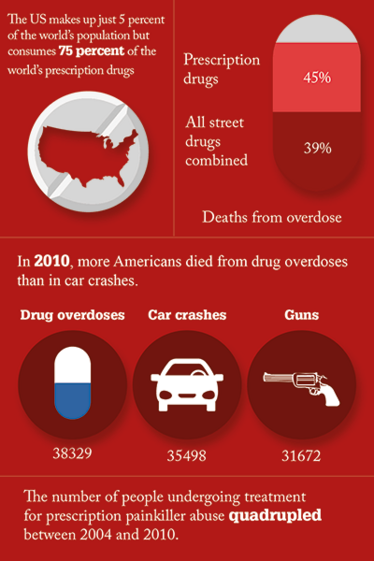

Prescription drug abuse has already reached epidemic proportions in the US – and other countries look set to follow the dangerous trend. What can drug makers do to help stem the tide?

Here in the US, prescription drug abuse is sweeping the nation. In 2012, an estimated 2.4 million Americans used prescription drugs non-medically for the first time within the past year, which averages to approximately 6,700 new users per day, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Prescription drug abuse is the non-medical use of a medication without a prescription, in a way other than as prescribed, or for the experience or feelings elicited.

In 2013, an estimated 24.6 million or 9.4 percent of the American population aged 12 or older were illicit drug users. Marijuana remains the most commonly used illicit drug with 19.8 million users (more than heroin and cocaine combined). Non-medical use of prescription drugs is the second largest category of abused drugs at 6.5 million users or 2.5 percent of the population. The Centers for Disease Control and prevention classified this phenomenon as an epidemic.

The classes of prescription drugs most commonly abused are opioid pain relievers, such as Vicodin or OxyContin; stimulants for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), such as Adderall, Concerta, or Ritalin; and central nervous system (CNS) depressants for relieving anxiety, such as Valium or Xanax.

Prescription opioid pain medications such as oxycodone and hydrocodone can have effects similar to heroin when taken in doses or in ways other than prescribed, and research now suggests that abuse of these drugs may actually ‘open the door’ to heroin abuse. There were 22,767 drug-related overdose deaths in 2013; 71.3 percent involved opioids. Gil Kerlikowske, the former national drug czar, said that the current culture of writing narcotic prescriptions for moderate pain, which began about a decade ago, must be changed and that doctors need to be retrained. The US makes up only 4.6 percent of the world’s population, but consumes 80 percent of its opioids – and 99 percent of the world’s hydrocodone, the opiate in Vicodin.

Nearly half of young people who inject heroin reported abusing prescription opioids before starting to use heroin, according to three recent studies (1). Some individuals reported taking up heroin because it is cheaper and easier to obtain than prescription opioids. Many of these young people also report that crushing prescription opioid pills to snort or inject the powder provided their initiation into these methods of drug administration.

The causes

Several issues are contributing to the rise in prescription drug abuse in the US:

Direct-to-consumer advertising

The public has been conditioned by the media and the pharmaceutical industry to believe that there is a pill available to cure every ailment. “Direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs has been legal in the US since 1985, but only really took off in 1997 when the FDA eased up on a rule obliging companies to offer a detailed list of side-effects in their infomercials. Since then the industry has poured billions of dollars into this form of promotion. The only other country in the world that allows direct-to-consumer drug ads is New Zealand (2). To date, there is a paucity of quantitative data on prescription drug misuse in New Zealand (3,4). However, New Zealanders as a population have some of the higher drug-use rates in the developed world, evidenced in the 2007/2008 New Zealand Alcohol and Drug Use Survey, which reports that one in six (16.6%) New Zealanders aged 16–64 years had used drugs recreationally in the past year (5). But the misuse of prescription drugs for their psychoactive effects is an international problem.

Perceived safety

Many believe that prescription drugs are safe to use non-medically because they are FDA approved, prescribed by a doctor and friends or relatives use the medication safely. What many people fail to recognize is that prescription drugs are effective in relieving pain or treating ailments when used properly under a doctor’s supervision.

Prescribing practices

The number of prescriptions for some medications has increased dramatically since the early 1990s. Opioid prescriptions have increased from 76 million in 1991 to 210 million in 2010. Stimulant prescriptions have increased from 4 million in 1991 to 45 million in 2010 (6). Unintentional overdose deaths involving opioid pain relievers have quadrupled since 1999. Over 970,000 prescribers wrote 259 million prescriptions for painkillers in 2012 (7).

Easy access

Unused prescriptions are frequently retained for future use in the family medicine cabinet, making them readily accessible for abuse. Most prescription drug abusers obtain their first experience free from friends or the family medicine cabinet. Drugs with high potential for abuse should be stored in a secure location and properly disposed of when no longer needed.

Information availability

Internet sites provide a wealth of knowledge on the manufacture and use of mind-altering substances. For example, websites like www.Erowid.com, www.Bluelight/ru.org and www.Drugs-forum.com offer personal experiences, information and support for addicts. The information age provides easy access to information that was previously only available through clandestine sources. Today, anybody with a smart phone or tablet has access to previously forbidden information. Because readers can learn how others abuse drugs they may feel they can do the same experiments safely.

Doctor shopping

Doctor shopping is a common practice where drug abusers visit several doctors in an attempt to obtain multiple prescriptions. The abusers frequently have their prescriptions filled at different pharmacies to avoid detection.

Dependence Versus Addiction

Physical dependence occurs because of normal adaptations to chronic exposure to a drug and is not the same as addiction. Addiction, which can include physical dependence, is distinguished by compulsive drug seeking and use despite sometimes devastating consequences.

Someone who is physically dependent on a medication will experience withdrawal symptoms when use of the drug is abruptly reduced or stopped. These symptoms can be mild or severe (depending on the drug) and can usually be managed medically or avoided by using a slow drug taper.

Dependence is often accompanied by tolerance, or the need to take higher doses of a medication to get the same effect. When tolerance occurs, it can be difficult for a physician to evaluate whether a patient is developing a drug problem, or has a real medical need for higher doses to control their symptoms. For this reason, physicians need to be vigilant and attentive to their patients’ symptoms and level of functioning to treat them appropriately.

The antidote

Federal and state governments have initiated numerous plans to reverse the trend of increasing prescription drug abuse by engaging importers, manufacturers, distributors, pharmacies, physicians and patients. Anyone who manufactures, distributes, dispenses, imports, or exports any controlled substance or who proposes to do so must obtain a DEA registration unless exempted by law (8).

In particular, the federal government is:

- Tracking prescription drug overdose trends to better understand the epidemic.

- Encouraging the development of abuse-deterrent opioid formulations and products that treat abuse and overdose

- Educating health care providers and the public about prescription drug abuse and overdose.

- Requiring that manufacturers of extended-release and long-acting opioids make educational programs available to prescribers about the risks and benefits of opioid therapy, choosing patients appropriately, managing and monitoring patients, and counseling patients on the safe use of these drugs.

- Using opioid labeling as a tool to inform prescribers and patients about the approved uses of these medications.

- Developing, evaluating and promoting programs and policies shown to prevent prescription drug abuse and overdose, while making sure patients have access to safe, effective pain treatment.

Many states have instituted prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP). A PDMP allows authorized users (including licensed healthcare prescribers eligible to prescribe controlled substances, pharmacists authorized to dispense controlled substances, law enforcement, and regulatory boards) to access patient controlled substance history information. The PDMP is committed to assisting in the reduction of pharmaceutical drug diversion without affecting legitimate medical practice or patient care. Currently, 49 states have PDMPs, which have been very effective in reducing prescription drug abuse. However, until a national database is developed, abusers will take advantage of the ability to visit neighboring states to do their doctor shopping.

Drug Enforcement Administration

The mission of DEA’s Office of Diversion Control (www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov) is to prevent, detect, and investigate the diversion of controlled pharmaceuticals and listed chemicals from legitimate sources while ensuring an adequate and uninterrupted supply for legitimate medical, commercial, and scientific needs.

“DEA is committed to reducing the destruction brought on by the trafficking and abuse of prescription drugs through aggressive criminal enforcement, robust administrative oversight, and strong relationships with other law enforcement agencies, the public, and the medical community,” said DEA Special Agent in Charge Keith Brown. “The doctors and pharmacists arrested are nothing more than drug traffickers who prey on the addiction of others while abandoning the Hippocratic Oath adhered to faithfully by thousands of doctors and pharmacists each day across this country.”

In 2005, DEA initiated a special operation (Distributor Initiative Program) to enforce provisions of the Controlled Substances Act requiring registrants authorized to distribute controlled substances to prevent diversion by designing and operating a system to identify suspicious orders and report them to DEA. The law defines suspicious orders as “orders of unusual size, orders deviating substantially from a normal pattern, and orders of unusual frequency”(9).

Americans can now take expired, unneeded, or unwanted prescription drugs to one of over 5,200 collection sites across the country free of charge and anonymous, no questions asked. Since its first National Take Back Day in September of 2010, DEA has collected more than 4.1 million lbs (over 2,100 tons) of prescription drugs throughout all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and several other US territories.

Abuse-resistant formulations

Opioid products are often manipulated for purposes of abuse by different routes of administration or to defeat extended-release (ER) properties. Most abuse-deterrent technologies developed to date are intended to make manipulation more difficult or to make abuse of the manipulated product less attractive or less rewarding. It should be noted that these technologies have not yet proven successful at deterring the most common form of abuse – swallowing a number of intact capsules or tablets to achieve a feeling of euphoria. Moreover, the fact that a product has abuse-deterrent properties does not mean that there is no risk of abuse. It simply means that the risk of abuse is lower than it would be without such properties. Because opioid products must be able to deliver the opioid to the patient, there may always be some abuse of these products.

Opioid products can be abused in a number of ways. For example, they can be swallowed whole, crushed and swallowed, crushed and snorted, crushed and smoked, or crushed, dissolved and injected. Abuse-deterrent technologies should target known or expected routes of abuse relevant to the proposed product.

As a general framework, abuse-deterrent formulations have been categorized by the FDA as follows:

- Physical/chemical barriers – Physical barriers can prevent chewing, crushing, cutting, grating, or grinding of the dosage form. Chemical barriers, such as gelling agents, can resist extraction of the opioid using common solvents like water, simulated biological media, alcohol, or other organic solvents. Physical and chemical barriers can limit drug release following mechanical manipulation, or change the physical form of a drug, rendering it less amenable to abuse (e.g., reformulated OxyContin).

- Agonist/antagonist combinations – An opioid antagonist can be added to interfere with, reduce, or defeat the euphoria associated with abuse. The antagonist can be sequestered and released only upon manipulation of the product. For example, a drug product can be formulated such that the substance that acts as an antagonist is not clinically active when the product is swallowed, but becomes active if the product is crushed and injected or snorted (e.g., Talwin Nx, Suboxone, Embeda).

- Aversion – Substances can be added to the product to produce an unpleasant effect if the dosage form is manipulated or is used at a higher dosage than directed. For example, the formulation can include a substance irritating to the nasal mucosa if ground and snorted (e.g., Oxecta oxycodone/niacin).

- Delivery System (including use of depot injectable formulations and implants) – Certain drug release designs or the method of drug delivery can offer resistance to abuse. For example, sustained-release depot injectable formulation or a subcutaneous implant may be difficult to manipulate.

- New molecular entities and prodrugs – The properties of a new molecular entity or prodrug could include the need for enzymatic activation, different receptor binding profiles, slower penetration into the CNS, or other novel effects. Prodrugs with abuse-deterrent properties could provide a chemical barrier to the in vitro conversion to the parent opioid, which may deter the abuse of the parent opioid. New molecular entities and prodrugs are subject to evaluation of abuse potential for purposes of the Controlled Substances Act. (e.g., Vyvanse amphetamine).

- Combination – Two or more of the above methods could be combined to deter abuse.

- Novel approaches – anything new that is not captured in the previous categories.

There are approximately 30 abuse-deterrent formulations currently under consideration for approval by the FDA. Used correctly, they do seem to have an impact. The most widely recognized opioid associated with the prescription drug epidemic is OxyContin, which was initially approved by FDA in 1995, with the reformulated version approved in 2010. The selection of OxyContin as a primary drug of abuse decreased from 35.6 percent of respondents before the release of the abuse-deterrent formulation to just 12.8 percent 21 months later (10). In April 2013 the FDA approved updated labeling for Purdue Pharma L.P.’s reformulated OxyContin (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release) tablets. The new labeling indicates that the product has physical and chemical properties that are expected to make abuse via injection difficult and to reduce abuse via the intranasal route (snorting).

The FDA approved Zohydro ER in October 2013, indicated for the management of pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment and for which alternative treatment options are inadequate. It was the first hydrocodone formulation that did not contain acetaminophen, unlike many immediate-release hydrocodone products, with the aim of reducing the risk for potential liver toxicity due to overexposure of acetaminophen. However, the FDA approval of Zohydro ER came against the advice of its own advisory committee, which expressed concerns about the potential for abuse. Since then, the drug has been at the center of ongoing controversy, with consumer groups and attorneys general of numerous states asking the FDA to reverse its approval of the drug, and bills introduced in the House and Senate to keep it off the market.

A major criticism of Zohydro ER has been that it was not available in abuse-resistant formulation. In September 2014, a coalition of more than 15 consumer groups and medical experts fighting the opioid epidemic called for new leadership at the FDA, charging that the agency’s opioid policies are exacerbating the nation’s epidemic of opioid addiction and overdose deaths. In October 2014, drug maker Zogenix announced submission of a supplemental New Drug Application for a modified formulation of Zohydro ER designed to have abuse-deterrent properties. The new formulation uses BeadTek, which, the company notes, “incorporates well-known pharmaceutical excipients that immediately form a viscous gel when crushed and dissolved in liquids or solvents.”

Pre-market studies

In April 2015 the FDA issued non-binding Industry Guidance: “Abuse-Deterrent Opioids – Evaluation and Labeling” (11). The guidance explains the FDA’s current thinking about the studies that should be conducted to demonstrate that a formulation has abuse-deterrent properties. The guidance makes recommendations about how those studies should be performed and evaluated, and discusses how to describe those studies and their implications in product labeling.

Studies designed to evaluate the abuse-deterrent characteristics of an opioid formulation should be scientifically rigorous and include the appropriateness of positive controls and comparator drugs, outcome measures, data analyses to permit a meaningful statistical analysis, and selection of subjects for the study. There are three areas of pre-market studies:

- Laboratory-based in vitro manipulation and extraction studies (Category 1). The goal of these studies should be to evaluate the ease with which the potentially abuse-deterrent properties of a formulation can be defeated or compromised. The resulting information should be used when designing Category 2 and Category 3 studies.

- Pharmacokinetic studies (Category 2). The goal of these studies should be to understand the in vivo properties of the formulation by comparing the pharmacokinetic profiles of the manipulated formulation with the intact formulation and with manipulated and intact formulations of the comparator drugs through one or more routes of administration.

- Clinical abuse potential studies (Category 3). In addition to their use by FDA, clinical studies of abuse potential are important for assessing the impact of potentially abuse-deterrent properties. The preferred design is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled and positive-controlled crossover study. These studies are generally conducted in a drug-experienced, recreational user population.

Currently, data on the impact of an abuse-deterrent product on drug abuse in the US population are limited, and thus the optimal data sources, study variables, design features, analytical techniques, and outcomes of interest of post-market epidemiologic studies are not fully established.

What can pharma do?

The pharmaceutical industry has spent billions of dollars developing abuse-resistant delivery systems for prescription drugs that have a high potential for abuse. This is a market-driven industry and companies engage in research if there is an economic benefit in producing abuse-deterrent drugs. It is not likely that the industry will continue to conduct expensive research needed to produce truly abuse-deterrent forms of controlled substances, unless incentives are offered. The FDA has approved abuse-deterrent labeling for several products that have demonstrated that their formulation is more difficult to abuse than currently available drugs. However, an area of concern that has not been addressed by the pharmaceutical industry is oral abuse by simply taking multiple dosage units. Should an abuser take more than the recommended dosage they will achieve the desired euphoric effect. This form of abuse does not require any time-consuming manipulation or extraction that may require equipment or chemicals.

In July 2012, the FDA approved a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for extended-release and long-acting (ER/LA) opioids approved for moderate to severe, persistent pain that requires treatment for an extended period (12). The REMS introduces new safety measures to ensure that the benefits of a drug or biological product outweigh its risks, while ensuring access to needed medications for patients in pain.

“Misprescribing, misuse, and abuse of extended-release and long-acting opioids are a critical and growing public health challenge,” said former FDA Commissioner Margaret A. Hamburg. “The FDA’s goal with this REMS approval is to ensure that health care professionals are educated on how to safely prescribe opioids and that patients know how to safely use these drugs.”

Under the new REMS, companies will be required to make education programs available to prescribers based on an FDA Blueprint. The REMS also will require companies to make available FDA-approved patient education materials on the safe use of these drugs. The companies will be required to perform periodic assessments of the implementation of the REMS and the success of the program in meeting its goals. The FDA will review these assessments and may require additional elements to achieve the goals of the program.

Training for prescribers

Based on an FDA Blueprint, developed with input from stakeholders, educational programs for prescribers of ER/LA opioids will include information on weighing the risks and benefits of opioid therapy, choosing patients appropriately, managing and monitoring patients, and counseling patients on the safe use of these drugs. In addition, the education will include information on how to recognize evidence of, and the potential for, opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction, and general and specific drug information for ER/LA opioid analgesics.

Updated medication guide and patient counseling document

These materials contain consumer-friendly information on the safe use, storage and disposal of ER/ LA opioid analgesics. Included are instructions to consult one’s physician or other prescribing health care professional before changing doses; signs of potential overdose and emergency contact instructions; and specific advice on safe storage to prevent accidental exposure to family members and household visitors.

Assessment/auditing

Companies will be expected to achieve certain FDA-established goals for the percentage of prescribers of ER/ LA opioids who complete the training, as well as assess prescribers’ understanding of important risk information over time. The assessments also cover whether the REMS is adversely affecting patient access to necessary pain medications, which manufacturers must report to FDA as part of periodic required assessments.

Modern medicine has provided a vast array of therapies to cure disease, ease suffering and pain, improve quality of life, and save lives. However, as with many new scientific discoveries and new uses for existing compounds, the potential for diversion, abuse, morbidity, and mortality are significant. Prescription drug misuse and abuse is a major public health and safety crisis. We must take urgent action to ensure the appropriate balance between the benefits and the risks. No one agency, system or profession is solely responsible for this undertaking; we must address the issue as partners in public health and safety (13).

The ultimate solution to prescription opioid abuse would be the development of a new entity that relieves pain without addictive or euphoric properties. Patients will have access to necessary pain medications without the risk of addiction and abusers will have no incentive to seek euphoria from such a new entity.

Holding Back the Tide

The not-for-profit Center for Lawful Access and Abuse Deterrence (CLAAD) was formed in 2008 by Michael C. Barnes, the current executive director and former counsel to the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. CLAAD and its coalition work with policy makers, law enforcement and patient advocacy organizations to reduce prescription drug abuse and optimize patient access to care, and abuse-deterrence is a central aspect of that mission. We speak with Kyle Simon, Director of Policy and Advocacy, to find out more.

Why is prescription drug abuse such a big problem in the US?

Several factors have led to what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified as a prescription drug abuse epidemic. Over-supply of opioid pain medications, lack of knowledge around how to treat pain that led to overprescribing and subsequent substance use disorders, criminals who caused the proliferation of pill mills and overdose-related events, and doctor shopping by people with substance use disorders all led us to where we are today.

What can drug companies do to tackle prescription drug abuse?

Researching, developing, and bringing to market medications that are less rewarding to divert, misuse, or abuse is a good start. Abuse-deterrent formulations (ADFs) are not a silver bullet, but by making medications harder to crush and snort or melt and inject, we can save lives and stem the epidemic. Additionally, companies must work with all sectors of society to educate the public that prescription drugs can be life-saving and help people lead healthy productive lives when used appropriately, but can be life-threatening when abused.

What evidence is there that ADFs are effective in reducing misuse?

A recent report by the manufacturer of reformulated oxycodone showed a reduction of about 20 percent in the number of prescriptions and overdose-related events. However, it’s important to re-state that ADFs are not a solution in themselves, just one part of a comprehensive approach to reducing prescription drug abuse – particularly for first-time opioid users who are not purposely seeking to misuse or abuse a medication.

What can be done to improve the poor uptake of ADFs?

The FDA recently finalized guidance for manufacturers of branded opioids that will serve as a road map for how to obtain ADF labeling. The same must be done for generic manufacturers so that commonly abused controlled substances can be made safer and brought to market. The delay in finalizing the guidance and lack of clarity by policy makers regarding exclusivity on the market still serve as obstacles, but we are seeing more products being developed.

Find out more at www.claad.org; @CLAAD_Coalition.

Smart Students Engineer a Solution

In response to the growing epidemic of prescription drug abuse, mechanical engineering students at John Hopkins University have developed a high-tech pill dispenser that is highly tamper resistant, personalized to the patient and can be opened only by a pharmacist. The device so impressed their mentors that they have applied for NIH funding to develop the prototype further. We spoke with Megan Carney, who developed the device along with her teammates.

What was your initial reaction to the project brief?

I was really excited at the possibility of creating a tamper-resistant pill dispenser because I thought it was a very interesting application of mechanical engineering. Drug abuse is a huge problem and designing something that could reduce the number of deaths from overdoses was very motivating.

Tell us about the device

The device is personalized to the patient only, secure and resistant to many household tools (hammer, drill, screwdriver), easy-to-use, and compact while also holding a month’s supply of pills. The device requires the patient to scan his or her fingerprint. The correct fingerprint activates the spring-loaded cartridge and rotating mechanisms to dispense the prescribed number of pills.

How difficult was it to come up with a feasible design?

We went through many rounds of designing and prototyping and then settled on a version of our final design around the winter of 2014 (halfway through the class). Once we had a rough outline of the design, we improved upon it by focusing on different components and testing them individually and then combining them and testing them as a cohesive system.

What was the most exciting part of the project?

I really enjoyed testing our device and seeing its results. A great moment was when a fellow student attempted to break into the device and couldn’t, despite many attempts and using a variety of household tools. That’s when we knew the device was really secure!

- NIDA, "How is Heroin Linked to Prescription Drug Abuse?", www.drugabuse.gov (November 2014).

- G. Humphreys, " Direct-To-Consumer Advertising Under Fire", Bull. World Health Organ., 87, 576–577 (2009).

- J. Sheridan et al., " Prescription Drug Misuse: Quantifying the Experiences of New Zealand GPs", J. Prim. Health Care 4(2), 106–112 (2012).

- World Health Organization, "Prescription Drug Misuse: Issues for Primary Care – Final Report of Findings" (2008).

- New Zealand Ministry of Health, "Drug Use in New Zealand: 2007/08 New Zealand Alcohol and Drug Use Survey" , health.govt.nz (2010).

- NIDA, "Prescription Drug Abuse", www.drugabuse.gov (2014).

- CDC Vital Signs, www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns (July 2013).

- DEA, Statement by J.T. Rannazzisi, Deputy Assistant Administrator, Office of Diversion Control (June, 2013).

- Title 21, United States Code, Sect. 823(b); Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations, Sect. 1301(b).

- T. J. Cicero et al., " Effect of Abuse-Deterrent Formulation of OxyContin", N. Eng. J. Med., 367, 187–189 (2012).

- FDA Guidance for Industry, "Abuse-Deterrent Opioids – Evaluation and Labeling" (April 2015).

- FDA News Release, "FDA Introduces New Safety Measures For Extended-Release and Long-Acting Opioid Medications" , www.fda.gov (July 2012).

- ONDCP Report, "Epidemic: Responding to Americas Prescription Drug Abuse Crisis" www.whitehouse.gov (2011).