More Trial, Less Error

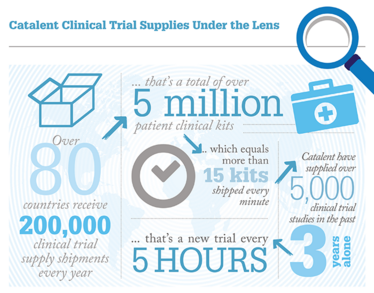

The pressure for increased efficiency pervades the pharma industry, including the clinical trials sector, where traditional supply models can lead to overstocking, waste and higher costs. Is there a more effective supply strategy?

sponsored by Catalent

The traditional approach to clinical trials’ supplies involves a centralized supply model, whereby primary packed materials are stored in bulk at a central warehouse and labeled with multi-lingual booklets, allowing central stock to be shipped to any site, regardless of local language. It’s a well-used model that appears to make sense. But does it?

Wetteny Joseph and Stephen Flaherty have both been instrumental in building Catalent’s clinical supply services. Joseph is President of Clinical Supply Services, but originally started out by working in the finance sector before transitioning to clinical supplies and using his experience to examine the cost drivers in the industry. Flaherty, on the other hand, has been leading the development of Catalent’s demand-led supply offering, which both he and Joseph believe is a far more flexible approach to clinical trials.

Trials and tribulations

There are many problems with a centralized supply model, most of which are caused by its inherent inflexibility. Supplies are sent to sites based on preliminary forecasts and planned recruitment at the start of the program. “This model is very static and linear – and tends to require long lead times in order to generate the batches and the unique labeling information, as well as to stockpile the finished patient kits,” says Joseph. “It is also industry practice to overshoot expected targets – often by 200 percent or more – which generates waste of both the product being trialed, and also the comparator products.” But the opposite can also happen in that demand may turn out to be far higher than expected, which can lead to stock outs, putting patients or the whole study at risk depending on the severity of the delay.

Another big challenge comes with changes. Indeed, the inflexibility of the traditional system hinders one’s ability to modify the trial design in response to early data. There are also added difficulties when attempting to modify the trial design, such as the addition of new countries or territories. It’s clearly not the most efficient method and, as Joseph adds, an inefficient supply chain “exponentially increases the cost of running trials”. Even the multilingual booklets themselves are a problem; not only can there be delays in getting the text approved (and a delay from one country will delay all of the booklets) but, from a usability point of view, it can also make it awkward for patients to find the relevant information.

Tradition on trial: the DLS approach

A few alternatives to centralized supply have emerged in recent years, including the ‘Just in Time’ model. “In reality, this is just an enhancement on the traditional model whereby stocks of partially finished patient kits are labeled and held at central depots, but there’s some customization that happens just before shipment, such as adding an investigator name. It still has some of the drawbacks of the traditional model in that you need to build up bulk supplies,” says Flaherty.

Instead, Catalent is developing a demand-led supply (DLS) approach, which is a decentralized approach to clinical supply. “It’s fast and efficient. Instead of pushing out large batches of packaged patient kits to clinics based on preliminary estimates, a continuous flow of kits is generated and they are only sent out in accordance with patient demand,” says Joseph.

Regional GMP facilities each hold small stocks of primary packed material, or “bright stock”, which are then secondary packaged, labeled and released only in response to specific requests from clinical sites, allowing companies to adapt to slower or faster recruitment in different countries. Since the bright stock is locally held prior to labeling, shipping times also tend to be faster and clinical sites can receive their supplies in a matter of a few days.

One might think that a central supply model would save costs due to its fixed, predicted demand and budget, but this isn’t actually the case. “A fixed model costs more than a demand-led system because it’s so wasteful,” says Joseph. “In the traditional model, patient kits are distributed to clinical sites based on recruitment forecasts, but we all know that patient recruitment is unpredictable, so stock often goes unused. And, as already indicated, there are also extra costs and time delays if anything needs to change.”

Furthermore, DLS eliminates the need for a multilingual booklet, which is replaced with single panel labels. “Each label can be patient- and country-specific, so it’s much easier for patients and clinic staff to use rather than finding the right page in a thick booklet,” says Flaherty. “As soon as you have a label approved for a given country, you could supply to that country, without the need to wait for the final, approved label text from the other countries within a booklet, which can be a bottleneck and delay start up of a trial."

Another aspect of improved efficiency associated with DLS is the ability to pool supplies. “With the bright stock staged at regional facilities, you can use it across multiple protocols because you’re only secondary packaging and labeling it when the demand arises,” says Flaherty. “Also, the flexibility of DLS permits items with the shortest expiry time to be used first; thus, with DLS, efficiency is increased, enabling material with varying expiry dates to be used much more effectively.”

DLS is a relatively new model of supplying clinical trials, but both Joseph and Flaherty are positive that it is an innovation genuinely needed by the industry in order to meet the challenges of today’s complex and far more sophisticated clinical trials. So far, it’s drawn a lot of interest because of its flexibility and speed, and the fact that it can be used for virtually any study, so Joseph and Flaherty are also positive about the future.

“Importantly, I think DLS also reflects the growing importance of the ‘voice of the patient’ in the pharma industry,” says Joseph. “We need to meet the needs of individual patients, including ensuring that they are not inconvenienced or placed at risk when patient kits are not supplied on time. DLS allows this – it’s a win for the patient, not just for the industry.”