Remote Controlled Drugs

The latest devices can deliver a drug in the right place and at the right time at the push of a button.

Brian P. Timko, Daniel S. Kohane |

Drug delivery technology evolved in part to address the deficiencies of conventional administration routes. When drugs are delivered by injection or in pills, it is difficult to achieve drug levels within the narrow window between toxicity and under-dosing. Furthermore, drugs with short half-lives have to be administered frequently or even continuously, potentially resulting in patient discomfort or inconvenience, or requiring tethering to external devices. Today, some of these limitations have been addressed by delivery systems that release therapeutics passively at a more-or-less constant rate for an extended period (1).

The problem with such systems is that they are not responsive to changes in the physiological state – or wishes – of the patient. Consequently, there has been a lot of research in developing drug delivery systems that can be triggered by the patient or physician to release drugs at the time and dose of their choosing or, in other words, on demand (2). These systems could be injectable, implantable, or in fact delivered by any means, and could be triggered multiple times. The potential stimuli for drug release include a wide range of energy sources, including light, magnetic fields, radio frequencies, or ultrasound. Triggered devices could make people’s lives better in a number of obvious ways; for example, in chronic pain, the patient could adjust the level of analgesia relief precisely to match their level of pain and activity. More sophisticated designs would allow programming of complex dosing regimens, or have built-in sensors to detect fluctuations in blood or tissue levels of molecules of interest, and have automatic mechanisms to release drugs in response to them. Controlling the timing of drug release is clearly important, but using the same sorts of triggers to control targeting of drugs within the body is another area of research focus (though this can also be achieved by old-fashioned methods such as implanting or injecting the drug delivery device). Controlling the dosing regime and precise localization of a drug in the body has a clear impact on efficacy and toxicity.

Pulling the trigger

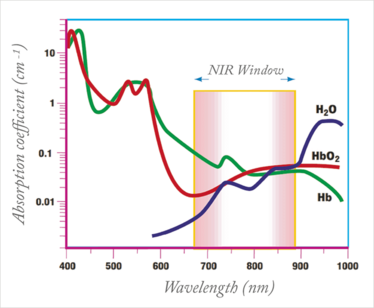

Near-infrared (NIR) light has attracted considerable attention as a trigger for drug release. It can penetrate relatively deeply into soft tissue because hemoglobin and water absorb the least light in that range of wavelengths (see Figure 1) (3). Moreover, NIR is already an established clinical tool, used for monitoring blood oxygenation levels within the body, deep-tissue fluorescent imaging or cancer therapy by hyperthermia (4). NIR light can be produced with relatively inexpensive and portable diode-based lasers that allow irradiation of only the target tissue. The devices are safe provided they produce light intensities below well-defined thresholds (5), and could be readily adapted for point-of-care use.

Figure 1. The NIR window, bound by hemoglobin (650 nm) and water (>900 nm) exhibits minimal absorption. Adapted from (3).

Going for gold

One way to trigger drug release with NIR light is by using gold nanoparticles, which come in a variety of shapes, such as rods, cubes or shells. Gold nanoparticles react to NIR light by producing heat in a process called surface plasmon resonance. The heat produced can be used to trigger another process; for example, to induce a change in a temperature-sensitive material built into the nanoparticle, resulting in drug release. In a seminal study, gold nanoshells were embedded in a macroscale hydrogel composed of the temperature-sensitive polymer poly(n-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAm) (6). Whereas most polymers swell when they are heated, pNIPAm hydrogels become hydrophobic and collapse when they are heated beyond 32°C. NIR light was used to heat (via the gold nanoshells) and collapse the polymer, expelling drugs. Many other systems have been developed based on the same general principle.

NIR-sensitive micro- or nanoparticles that contain drugs represent another route and offer the additional benefit that they are injectable. Temperature-sensitive liposomes, which typically release drugs passively, have been conjugated to gold nanorods to achieve NIR sensitivity. NIR irradiation disrupts the liposome, enabling release of the loaded drug (7). Hollow gold nanocages coated with pNIPAm have been loaded with drugs. NIR irradiation collapsed the polymer, opening pores through which the drug could be released. (8)

The wavelengths of light that cause heating of gold nanomaterials (based on absorption spectrum) are highly dependent on particle sizes and geometry. By tuning the shape and size of the nanoparticles, the drug delivery system can be adapted to any light source within the visible or near-infrared range. Systems can also be composed of two populations of particles that are triggered by lasers firing nonoverlapping spectra, enabling independent dosing of two or more distinct drug types (9).

Reservoir drugs

Remotely-triggered drug delivery systems must be designed so that the range of achievable drug release rates is therapeutically acceptable. Moreover, the ratio between the fully-on and fully-off states of the device should be as high as possible so that baseline drug leakage, which reduces the lifetime of the device and could cause side effects, is minimized.

One way to achieve consistent, reproducible drug release is with reservoir-based systems, in oral, transdermal or implantable formulations, designed to achieve sustained or pulsatile release profiles. Some have already undergone clinical trials for treating conditions such as diabetes, osteoporosis or macular edema (10), and contain enough drug for weeks or months of therapy.

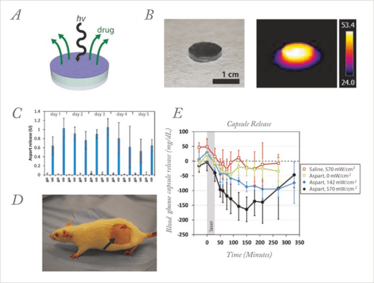

We recently developed an implantable reservoir that could be loaded with tens or hundreds of doses of drug and triggered with NIR light (see Figure 2A). The drug is contained in a capsule bounded by a hydrophobic membrane that is impermeable to the drug. The membrane contains an interconnecting network of nanoparticles based on pNIPAm and gold nanoshells. When irradiated with NIR light, the drug is released through pores that are created in the membrane via pNIPAm collapse (see Figure 2B) (4).

Figure 2. NIR-triggered capsules. (a) Schematic of device. (b) (left) Photograph of a typical device, and (right) thermal image of the same device uniformly irradiated with 808 nm light at 186 mW/cm2. (c) Release from devices over 30-min dosing cycles. Devices were turned on with 570 mW/cm2 laser light twice per day for 5 days. Off-state release was measured 30 min before laser triggering (n = 3). (d) Photograph of a rat with an implanted capsule (black arrow). (e) One day after device implantation, blood glucose levels were measured after triggered release from devices filled with saline (n = 4) or aspart solution by using an NIR trigger (30 min duration; gray box) of 0, 142, or 570 mW/cm2 irradiance (n = 4, n = 3, and n = 6, respectively). All data are means ± SD. Adapted from (4)

Drug delivery rates could be modulated by adjusting the thickness or composition of the membrane. More importantly, the specific rate of drug release could be modulated by adjusting the intensity of the NIR light. As a proof of concept, we designed devices that could treat diabetic rats. Typically, a dose of 1 unit of insulin – or, in our case, a fast-acting analog such as aspart – is enough to reduce blood glucose to normal levels. We built devices loaded with over 100 doses of aspart, sealed with a membrane designed to release approximately 1 unit of aspart when triggered for 30 minutes with a laser (see Figure 2C). The devices were implanted beneath the skin of diabetic rats (see Figure 2D), and could be triggered multiple times over a 14-day period. Figure 2E shows the typical glucose response after a 30-minute NIR pulse. The blood glucose level reached a minimum about 150 minutes after triggering, but notably the magnitude of glycemic reduction could be controlled by the intensity of the laser pulse – a stronger pulse achieved a greater reduction.

If coupled to a glucose monitor, systems like these could tailor dosing to the level of hyperglycemia. They could also be used to achieve localized drug release. For example, they could be placed on a nerve, giving the patient the capability for precise titration of local analgesia to match actual needs and circumstances. These devices can moreover be used to deliver a wide range of drug types from small molecules to macromolecules, and therefore could be useful for treating a wide range of disorders (11).

Safety

Despite the abundance of triggered drug delivery systems, relatively few have made it into the clinic. Systems that show potential in humans will certainly need to undergo a thorough battery of tests to ensure patient safety; for example, the NIR light itself could cause burns at sufficiently high powers and/or irradiation times, which is particularly relevant in patient-controlled devices, where the a device may be activated repeatedly. Materials for drug delivery should be designed so that the irradiance required to fully activate the device is minimized, particularly in the case of systems placed deep within tissues, where a substantial portion of the light is absorbed and scattered, leading to heating.

As with all drug delivery systems, the biocompatibility of the NIR-activated carrier and the drug contained within is important (12). The biocompatibility, biodistribution and other biological parameters of some materials – including nanomaterials – is still ill-defined. Local tissue reaction to the drug released is another important concern, particularly in the case of sustained-release systems, where pharmacokinetics may differ substantially from those of injected doses. In particular, local drug levels may be much higher for much longer duration than with systemic delivery. Finally, the device may be susceptible to biofouling, degradation (which may be a good thing), and biodistribution of any possible degradation products.

Looking ahead

As NIR-triggered devices can, in principle, release drugs in any temporal profile – pulsatile, sustained, crescendo, and so on – they enable dosing regimens that are not achievable by conventional means. NIR can also be used to target nanoparticle carriers to specific tissues (13), enabling localized drug delivery after systemic intravenous injection (see Figure 3). Such targeted release may help to reduce side effects for drugs that are locally effective but systemically toxic – a great example is cancer chemotherapy.

In short, NIR-triggered drug delivery systems could enhance efficacy, reduce side effects, increase patient compliance and, ultimately, give patients greater control over their lives. Certainly, there is much to consider in terms of both safety and efficacy in the future, but we feel the huge potential benefits are well worth the effort.

- B. P. Timko et al., “Advances in drug delivery”, Annual Review of Materials Research 41, 1–20 (2011).

- B. P. Timko, T. Dvir and D. S. Kohane, “Remotely Triggerable Drug Delivery Systems”, Advanced Materials 22 (44), 4925–4943 (2010).

- R. Weissleder, “A Clearer Vision For In Vivo Imaging”, Nature Biotechnology 19, (4), 316–317 (2001).

- B. P. Timko et al., “Near-Infrared–Actuated Devices For Remotely Controlled Drug Delivery”, PNAS, 111, (4), 1349–1354 (2014).

- American National Standards Institute and Laser Institute of America, “American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers”, Laser Institute of America, Orlando, FL (2000).

- S. R. Sershen et al.,“Temperature-Sensitive Polymer-Nanoshell Composites ForPhotothermally Modulated Drug Delivery”, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research 51, (3), 293–298 (2000).

- G. H. Wu et al., “Remotely Triggered Liposome Release by Near-Infrared Light Absorption via Hollow Gold Nanoshells”, Journal of the American Chemical Society 130, (26), 8175 (2008).

- M. S. Yavuz et al., “Gold Nanocages Covered By Smart Polymers For Controlled Release With Near-Infrared Light”, Nature Materials 8, (12), 935–939 (2009).

- A. Wijaya, “Selective Release of Multiple DNA Oligonucleotides from Gold Nanorods”, Acs Nano 3, (1), 80–86 (2009).

- C. L. Stevenson, J. T. Santini and R. Langer, “Reservoir-Based Drug Delivery Systems Utilizing Microtechnology”, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 64, (14), 1590–1602 (2012).

- T. Hoare et al., “Magnetically-triggered Nanocomposite Membranes: a Versatile Platform for Triggered Drug Release”, Nano Letters 2011, 11, (3), 1395–1400 (2011).

- D. S Kohane and R. Langer, “Biocompatibility And Drug Delivery Systems”, Chemical Science 1, (4), 441–446 (2010).

- A. Barhoumi et al., “Photothermally Targeted Thermosensitive Polymer-Masked Nanoparticles”, Nano Letters, 14, (7), 3697–3701 (2014).

Instructor in Anesthesia at Boston Children’s Hospital.