The Shape of Proteins to Come

A new technique allows scientists to see conformational changes caused by ligand binding in real time, opening up new screening options for drug discovery.

Protein conformational changes play a key role in signaling (after all, changes in shape cause changes in function); however, it has been difficult to study those changes in real time. Crystallography, dual polarization interferometry, and binding assays have all been used, but inherent limitations have curtailed widespread use. Now, with a new technique based on the optical principle of second harmonic generation (SHG), biophysics start-up Biodesy hopes to put conformational data in the hands of scientists around the world. Investors currently include pharma giants Pfizer and Roche – and Biodesy’s first commercial system launched in January 2016.

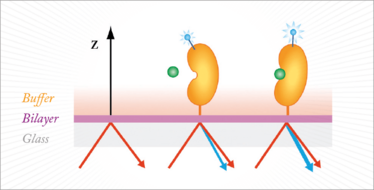

The technique involves labeling the protein of interest with proprietary dyes and tethering them to a lipid bilayer surface (Figure 1). A femtosecond laser is applied, causing the dyes to generate second harmonic light. The intensity of the signal correlates with the position of the label relative to the surface, and hence the magnitude and direction of the conformational change can be calculated.

Figure 1. Ligand binding triggers a conformational change that brings the label towards the surface normal, increasing signal (blue light). Conversely, movement of the label away from the normal results in a reduced signal.

A new angle

Biodesy founder and CSO Josh Salafsky has always been fascinated by the intersection of physics and biology. “I liked the idea of bridging those two worlds, and applying physical tools and ideas to biological systems,” he says.

A few months into his post doc at Columbia University, sitting in a lab meeting, he was struck by an intriguing idea. “I realized that there was the possibility of labeling a biomolecule so that you could detect it by SHG. It was an analogous idea to fluorescence, or any other label-dependent detection modality, but it just so happened that no-one had really thought to do it with SHG.”

SHG has been used to study the organization of molecules in inorganic compounds, but not typically for biological molecules. Convinced that SHG held promise for studying structural biology, Salafsky started working on the technology full-time. The discovery that SHG could be used to detect conformational change (and with very high sensitivity) soon followed and, with encouragement from colleagues at Columbia, became the main focus.

“SHG has a number of properties that make it almost tailor-made for looking at protein structure – and for doing high-throughput drug discovery experiments,” says Salafsky. “In particular, SHG is much more sensitive to Ångström-level movements of a label caused by structural change than other common techniques like fluorescence. And SHG can be measured easily in real time in a physiological environment, unlike other high-resolution techniques like crystallography.”

The first iterations of the technology did not quite match up to the automated, high-throughput machines demanded by the pharma industry, however. “The rudiments of that first setup are actually still found in the marketed product – the Biodesy Delta – but it lacked the high-throughput capabilities and sensitivity that we have now,” says Salafsky.

One of the first prototypes took up residence in Salafsky’s garage, generating data for several published papers (photo right). It was while working with this original garage setup that Salafsky had a breakthrough moment. “I was doing some experiments on integrins provided by Timothy Springer at Harvard. I applied a control peptide: no change. Then I added a peptide that stimulates conformational change, just one amino acid different than the control peptide, and I saw a change in the signal. That was the moment I knew that I was seeing conformational change caused by ligand binding. I felt that this could be used in so many different ways for drug discovery and basic research. And I knew how easy the process was because I was doing it in my garage! I knew I had something.”

The Journey So Far

2000

Initial concept to label biomolecules to detect them by SHG

2002

Initial concept to use SHG to detect conformational change in biomolecules

October 2013

Biodesy, Inc. founded; Series A funding raised

January 2014

Biodesy Delta product development started

December 2015

20th pharmaceutical customer signed

January 2016

Biodesy Delta launched; Series B funding raised

An early prototype in Joshua Salafsky’s garage.

The birth of Biodesy

In 2013, Biodesy was ready for the next step. Formerly entrepreneur-in-residence at GE Healthcare, Greg Yap met Salafsky during early financing discussions, and was immediately drawn to the concept. “It was the combination of the potential for something really game-changing, together with a near-term opportunity to make a difference in drug discovery,” says Yap. “My whole career has been based at the intersection of biology and business. I am always looking to translate discoveries into impact, to help move medicine forward, and Biodesy has the opportunity to do just that.”

Yap joined the company as CEO and co-founder, and helped Biodesy secure an initial $15 million investment to commercialize the technology. The name Biodesy (pronounced bi-odyssey) was inspired by the scientific field of geodesy. “Geodesy is the study of the shape of planets, and Biodesy stands for the study of the shape of biological molecules,” explains Salafsky.

Prior to the product launch, the company has been offering the technology as a service, and their clients include seven of the top 10 pharma companies. “Now we’re in the process of migrating those customers over to using the product,” says Yap. “Our goal was always to get instruments into customers’ hands, so that they could do experiments in their own labs.”

The same properties that made the Biodesy prototype simple enough to run in a garage, now make the final product easy to use in the lab, according to Salafsky. “You don’t have to know anything about SHG to run a Biodesy Delta. Someone can learn to use it in a day – and they don’t need to be a PhD scientist.”

Left: Greg Yap, co-founder and CEO of Biodesy. Right: Joshua Salafsky, inventor of the technology, and co-founder and CSO of Biodesy.

There has been lots of interest in the technique, says Yap: “Pharmaceutical companies are keen to use the technology for high-throughput screening, to identify new hits, to characterize and differentiate those hits, and to understand the mechanism of action in the discovery pipeline. There has also been a tremendous amount of interest from basic researchers. Nearly every researcher is studying an interaction of some kind but relatively few of them get access to structural information at the moment, because of the expense, time and expertise required.”

An application the team hadn’t initially considered – but which pharma customers were keen to explore – was screening for allosteric compounds, which bind outside the active site. “These are sites that are often not seen in crystal structures, which only provide a static snapshot. By screening proteins in solution you’re in a good position to identify binding sites that might open only fleetingly,” says Salafsky, “With any totally new technology, it is often customers who figure out some of the most interesting applications. And as we get the technology into customers’ hands, the applications are expanding.”

“Drug discoverers have never been able to screen based on the conformational change induced by a ligand or inhibitor,” adds Yap, “So that’s something very exciting to pharmaceutical and academic scientists alike.”

An ongoing odyssey

The team continues to work on improving and expanding the system. Long-term, the technology has the potential to develop into a quantitative structural method, measuring angular change in the protein to model protein structures and structural motion in real time.

Launching the product onto the market is just the start, says Yap. “The company is a testament to Josh’s talent and perseverance. Not just in having the original insight, but sticking with it through all of the work to make it practical. It’s a tremendous journey, and we’re only just getting started.”

So what advice does Salafsky have for other budding scientist–entrepreneurs? “Do what you love, because you’ll need that drive to keep you going; it is a lot of hard work and uncertainty for a long time. But most of all, never sacrifice the quality of the science,” concludes Salafsky.

Charlotte Barker is the Editor of The Translational Scientist (www.thetranslationalscientist.com), a sister publication to The Medicine Maker. This article was first published in The Translational Scientist.