The Great British Debate

As politicians and the public argue over the minor point of the UK leaving Europe, we ask a more important question: what will a “Brexit” mean for the global pharmaceutical industry?

The European Union (EU) is a coalition of 28 countries that have all agreed to cede certain aspects of national sovereignty in return for the benefits of global political influence and economic security. Whatever your opinion on the costs and benefits of this trade-off, there is no doubt that the EU, with a population of over 500 million citizens and some of the best-funded healthcare systems in the world, is a very important market for the pharmaceutical industry.

But the EU can look a little fragile a times. Unemployment is persistent (~9 percent on average and ~25 percent in some member countries); keeping weaker member countries afloat seems to be a constant burden; and developing a rapid, coordinated and effective response to external crises, such as an influx of refugees, is difficult when the disparate views of 28 members must be taken into account.

On June 23, 2016, the British public will be asked to decide whether or not the UK should remain a member of this complex coalition. How likely are the British to walk away from their cross-channel colleagues? Difficult to gauge. What are the likely consequences of such a ‘Brexit’ – not just for pharmaceutical companies based in Britain and Europe, but for those trying to sell into one or both of these markets? An even more complicated question. Our crystal ball is far from clear, but here we try to throw some light on the subject – and, importantly, what it means for the global pharma industry.

The past is a foreign country

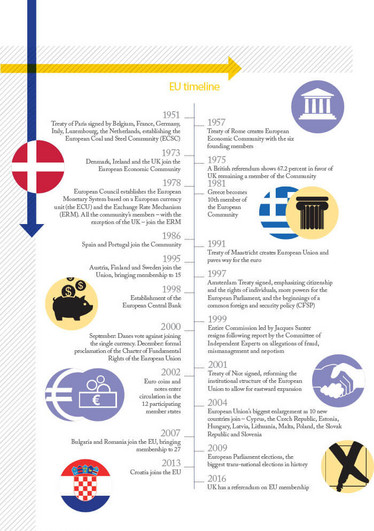

Understanding Britain’s sometimes strained relationship with EU institutions requires a short history lesson. In 1973, Britain joined the European Economic Community (EEC) – basically a trading bloc in which member countries agreed to impose no customs duties on each other’s goods and services, while imposing common tariffs on products from outside the EEC. Two years later, in the 1975 referendum, pragmatic Brits voted to remain in the EEC. But since then, the EEC has evolved into the European Union – a very different creature, with its own flag, central bank, Supreme Court, parliament and president. “What was originally sold to the British people as an economic union has now become a political and social union,” explains Neil Hunter, Life Science & Corporate Communications Director, at Image Communications Box Ltd.

With EU laws and courts superseding Britain’s own, some Brits feel their country is being slowly absorbed into a foreign behemoth run by those with little regard for the UK’s wishes or needs. “With each treaty, the EU accumulates more power,” says Hunter. “The EU is marching closer to political unity with the end goal of a super-state: the United States of Europe.” Given this fear, and given that the EU doesn’t look as stable or as strong as the EEC of the 1960s and 70s, it’s not surprising that the same pragmatic citizenship that voted to join the EEC may now be wondering about leaving the EU.

Polls have suggested that the majority of British citizens are ‘Eurosceptic’ (1) – which is to say, critical of the EU and its institutions. Despite this, it would seem that the UK is also nervous of change. Indeed, at the time of writing, most opinion polls suggest that the population is slightly in favor of remaining in the EU. Nevertheless, with older voters more likely both to support the ‘leave’ camp and to actually make the effort to vote, the result could be a very close call (2). Whichever way the British vote falls, the fact that the referendum is happening at all signals discontent and instability within Europe. And if Britain leaves the EU – taking with it a large contribution to the EU budget – the costs of events such as the Greek bail-out and the migrant crisis will have to be shouldered by a smaller core of wealthy member countries. Consequent tensions could fuel Eurosceptic parties in other EU members – and potentially lead to more referendums. The potential of a ‘Grexit’ (Greek withdrawal from the Eurozone) has been in discussion since around 2010, and there are rumblings of discontent in other EU countries too; thus, there is potential for a Brexit to cause a domino effect and to fragment the EU. “A number of countries are already talking about having their own referendums if Britain votes to leave the EU,” says Hunter. “A vote to stay could strengthen the EU in its ambitions for closer union. But a vote to leave could lead to the unraveling of the entire project.”

Who cares?!

Even if you live outside of Europe, the scale of the decision and potential for further change is important. In a speech made at the end of April in London, Barack Obama stated, “Ultimately, this is something that the British voters have to decide for themselves [...] And speaking honestly, the outcome of that decision is a matter of deep interest to the United States because it affects our prospects as well,” (3).

Pharma is a global industry and the EU is one of its most important markets, so the potential for a Brexit matters. In particular, the UK often serves as an entry point to the EU market for foreign companies. If Britain lost – or ended up with limited access to – the EU “single market”, these firms may need to look elsewhere when launching new products. There may also be consequences to global supply chains, such as the flow of ingredients, equipment and consumables.

Indeed, one of the concerns expressed by anti-Brexit campaigners is that Britain might lose access to the EU single market. Whether or not this would actually happen is debatable. EU treaties stipulate that if no agreement is reached within two years, the UK would revert to World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, whereby the UK’s exports to the EU and other WTO members would be subject to tariffs. The UK would also likely introduce an import levy on goods coming from the EU to provide equal treatment between goods imported from EU member states and other third countries – but there are other options (see Post-Brexit Realities).

With the US and the EU currently negotiating the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), a vote to leave could position Britain outside of both the European single market and the new EU-US market. In that case, British goods exported to the US would face tariffs and so British companies could be at a disadvantage to EU-based competitors. In his speech, Obama explained, “Down the line, there might be a UK-US trade agreement, but it’s not going to happen anytime soon, because our focus is in negotiating with a big bloc, the European Union, to get a trade agreement done [...] trying to do piecemeal trade agreements is hugely inefficient.”

But the TTIP is by no means a done deal, and has taken a very long time to get to this stage – a consequence, Eurosceptics would say, of needing to take into account the wishes of 28 different members.

According to Angus Dalgleish, Professor of Oncology at St George’s University of London (and a member of the ‘Leave’ campaign), one of the frustrating aspects of being tied to the EU is the red tape associated with EU regulation. “90 percent of companies in the UK don’t even trade with the EU, but they still have to adhere to EU regulations,” he says. Moreover, an individual country within the EU, such as the UK, cannot negotiate trade agreements with non-EU countries. Such deals are done on an EU-wide level on behalf of all member countries, which can take a significant amount of negotiation since all 28 EU stakeholders need to agree.

Accordingly, many in the UK are frustrated with the speed at which the EU negotiates trade deals; Eurosceptics point out that smaller non-EU nations, such as Iceland, have been able to rapidly negotiate agreements with countries like China. And for European pharma companies, there are many markets outside of the EU that are clearly of interest. “As Asia, South America, and Africa continue to develop, there will be a huge demand for pharmaceuticals,” says George Chressanthis, Principal Scientist at Axtria and former Senior Director for Commercial Strategic Analysis at AstraZeneca. “Brexit would certainly give the UK a much greater, freer hand to negotiate free trade agreements with the growth markets in the developing world.”

Helen Roberts, a lawyer at BonelliErede, concurs: “If Britain could negotiate bi-lateral trade deals with non-EU nations, for example with China or Latin America, UK-based pharma companies might benefit from freer trade – in the form of reduced customs duties, for example – if it could offer a significant trade benefit over trading with the EU market.”

But there are warning voices too. “Trade between UK and EU pharmaceutical companies may be significantly restricted if the UK does not arrange a free-trade deal with the EU post-Brexit,” says Davide Levi, Managing Director of Navigant’s Life Sciences Practice. “Due to greater ease of generic entry in the UK, prices in the UK often decrease faster compared to markets such as France and Germany, making exportation attractive. UK drug prices may be removed from other states’ international reference pricing baskets; potentially reducing prices across Europe as prices in the UK are typically higher than average. If this occurs, it could serve to make product launches in the UK less attractive.”

Similarly, UK-based biopharma companies are currently free to sell their products to the EU without trade barriers, and the same goes for companies in the EU selling to the UK market (which was ranked in the top ten global markets in 2013 [4]). A Brexit may require these companies to change their domicile to an EU country to continue to enjoy the same tariff-free trade with the EU.

Scientifically speaking

As well as impacting pharma companies via trade, a Brexit could also have a more direct impact on scientific research. At present, the EU, via the European Research Council (ERC), supports EU-based scientific research through grants allocated on the basis of “peer-reviewed excellence”, regardless of political, economic or geographic considerations. The UK contributed nearly £4.3 billion for EU research projects from 2007 to 2013, but received nearly £7 billion back over the same period, so some UK scientists fear that a Brexit would result in a net loss of research funding (5). However, Eurosceptics claim that the shortfall would be made up from savings gained by no longer contributing to the total EU budget.

Another point is that the EU facilitates collaborations between EU scientists. “Science is such a large-scale collaborative undertaking these days that viewing it in national units makes little sense,” says Mike Merrifield, a professor at the University of Nottingham. However, Chris Leigh from Liverpool John Moores University, argues that, if anything, collaborative work outside of the EU would increase. “In order to control overall inward migration, the UK government is having to restrict entry from non-EU countries to counteract migration from EU countries, which means that non-EU scientists are having to cover additional costs and jump through many hoops to work in the UK.” For more discussion about the impact on science, see Helping or Hindering Science?

Finally, when it comes to the regulation of medicines, being in the EU has advantages for the globalized pharma industry; harmonized regulations mean that pharma companies don’t have to adhere to multiple regulatory systems to sell to different EU nations. Thus, companies from outside the EU can launch their drugs in the UK and throughout the EU via a single regulatory body. In the case of a Brexit, companies that wanted to launch their drugs in the UK may have to go through a UK-specific regulatory body (the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency [MHRA]). Dealing with any regulatory body can be a headache for pharma – and there are already frustrations at the differences between EMA and FDA procedures.

“Sharing a common regulatory agency and common market with the entire EU is a benefit for the UK. While the UK is likely to strike trade deals with non-EU nations in the event of Brexit, it is unclear whether this will make up for the loss of EU and EMA membership,” says Levi. “From the perspective of a large pharmaceutical firm, the need to work with an additional regulatory agency, while somewhat inconvenient, would not be a significant cost and is unlikely to discourage investment in the UK but the challenges for small companies may be greater.”

From a more logistical point of view, a Brexit could have implications for the EMA itself; EU rules stipulate that the EMA must be based within the EU, so it would likely have to move its headquarters from London. Some European countries would perhaps rejoice at this news; Anders Blanck, Director General of the LIF group representing research-based drug-makers in Sweden, has already been encouraging the Swedish government to immediately launch an intensive lobbying campaign to make Sweden the new host country for the EMA (9).

Conversely, those campaigning to leave point to the cost of EU directives for small businesses and medium sized enterprises. Dalgeish claims it costs UK business more than £33 billion a year. He decided to campaign for Britain to leave the EU after an anti-cancer drug he was working on was denied approval by the EMA because of the Clinical Trials Directive. “Without the backing of a large pharmaceutical company there was no way to carry out further studies of the scale the EMA wanted – it would have cost over £2 million,” says Dalgleish. Work on the drug had to stop, but Dalgleish believes that had it been left to UK regulators, the drug probably would have been approved. “There’s some evidence that even people in big pharma find the barriers and costs too high to do the clinical studies they want to,” he adds.

Daniel Hannan, a Member of the European Parliament and another member of the ‘leave’ campaign also targeted the directive. “Britain has just 1 percent of the world’s population, but in 2004 we were carrying out 12 percent of the world’s clinical trials, but when the directive came in, this went down to 1 percent. I think we can do better without those directives.”

The Clinical Trials Directive has been criticized by many in the global pharma industry, so much so that a reformed version will come into play after May 28, 2016. The new directive has not settled all of the critics, but a functioning clinical trials regulation encompassing the EU inarguably has its benefits because you can use one process to apply to conduct clinical trials in multiple EU countries. What would happen if the UK were to be outside of that process? Would companies bother going through a separate process or would they just use an EU site?

Helping or Hindering Science?

How important are EU science programs to UK science?

Mike Merrifield: The main attraction isn’t actually the funding, but the structures provided by Horizon 2020 and other EU initiatives. For example, the EU provides very effective mechanisms for setting up exchange programs of both junior and senior researchers, with integrated training programs and other ways of sharing expertise.

Chris Leigh: There are some universities and research groups that rely on EU funding, but for the bigger picture, the EU only funds around 3 percent of the UK’s research and development base. Even in the extremely unlikely event that we cut all ties with EU science networks, it would be hard to argue that the overall impact would be much greater than this 3 percent figure. It’s also important to note that EU science funding represents around 3-4 percent of our net contribution to the EU project.

Steve Bates: The UK is a net recipient of EU funding for its health research, accessing more funding per capita than any other country. Since 2007, UK scientists have received around £3.7 billion from the EU. As of 2011, the UK won 16 percent of all FP7 funding to EU member states and 27 percent of European Research Council funding. These fractions are higher than the overall UK contribution to the EU budget (about 11.5 percent) and the UK’s share of overall EU spending (about 5.6 percent).

Would Brexit mean an end to the UK’s participation?

Merrifield: Those in favor of Brexit point to countries like Israel, who are “associated countries” of the Horizon 2020 program, and hence can benefit from the funding that it offers. Those opposed to Brexit point to Switzerland, which has a longstanding involvement with these programs, but their agreement is tied in with free movement of people between Switzerland and the EU, and unless they extend their current free movement arrangements to include Croatia, they will lose access to EU science programs at the end of 2016. One cannot say definitively how closely the UK would remain associated with these programs post-Brexit.

Leigh: Switzerland had an agreement in place with the EU but, after they voted against free movement in a referendum, they reneged on that agreement. The UK situation would be different as any negotiations and subsequent agreement would have to be determined in the two years after a Brexit vote. I’d also point out two things. Firstly, Israel is a net beneficiary from their involvement in EU science networks and yet has no free movement agreement with the EU. Secondly, CORDIS data shows that Switzerland is still very much involved in EU science networks – more so than the UK on a per capita basis. The only difference is that the Swiss government picks up the tab for some of the projects.

Bates: Outside the EU, it seems likely that UK life sciences would be shut out from such funding schemes. There has been no proposal put forward for the sector to consider where the money might come from to replace this in the scenario of the UK leaving the EU. Several UK life science companies have found the Horizon 2020 process difficult and over burdensome to manage. However, this process issue can be overcome. What access to equivalent funding and collaboration would look like if the UK left the EU is not clear, and hence not a compelling alternative to the current situation. The value of funding schemes is not only in the hard cash they provide, but also in the collaborations they facilitate.

You Spin Me Right Round

In the run-up to the 2015 General Election, David Cameron, promised that he would hold an in-out referendum on the country’s EU membership – after a “renegotiation” with the EU. His words appeased his Eurosceptic voter base – and after he won, there was no backing out. Cameron deliberated with European leaders and then presented to the British people a letter containing the details of some – arguably small reforms (mainly to in-work benefits EU migrants are eligible for) and proclaimed the negotiation a success. Since then he been strongly campaigning for Britain to remain in the EU. Others calling for the UK to remain within the EU include Barack Obama (President of the US) and Shinzo Abe (Prime Minister of Japan).

The Picture of Divorce

Levi suggests the UK could strike a deal to remain in the EMA, or create a regulatory agency that manages to mirror much of the EMA’s guidance, with the ability to opt out of any directives and regulations it doesn’t want. “The thought of Britain leaving the EU creates a lot of uncertainty as to what potential effects it might have – especially if policy developments are required,” adds Chressanthis. “Companies may not like the current environment, and a different path may even lend itself to something better, but change creates uncertainty – and businesses by and large don’t like uncertainty.”

The precise effect of a Brexit will depend on how the UK responds in terms of future legislation and incentives for the pharma industry, and is difficult to predict. However, many executives, such as Andrew Witty from GlaxoSmithKline and Eli Lilly’s John Lechleiter, have support Britain remaining in the EU (7). The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) has also been vocal on this issue, claiming that “the UK’s continued membership of the EU is in the best interests of the pharmaceutical industry in the UK and across Europe” (8). UK industry bodies, such as the BioIndustry Association (BIA), are also supportive of the UK remaining with the EU. “Feedback from BIA member companies of all sizes has been unanimous in calling for the UK to remain in the EU as it acts as a catalyst for scientific collaboration and development across all member states,” says Steve Bates, CEO of the BIA. “By being part of the EU, the UK has the opportunity to demonstrate the benefits of its progressive science based approach to the wider EU members and has a strong and powerful voice to influence change in the European market.”

Post-Brexit Realities

Is leaving the EU really a “leap in the dark” for the UK? Helen Roberts, solicitor at BonelliErede and a former member of the UK Regulator for Promotion of Medicines (PMCPA) attempts to shine a light on the possibilities for Britain post-Brexit.

World Trade Organization model

Under WTO rules, each member must grant the same ‘most favored nation’ (MFN) market access, including charging the same tariffs, to all other WTO members. As a WTO member, the UK’s exports to the EU and other WTO members would be subject to the importing countries’ MFN tariffs. Compared with EU or EFTA membership, this would raise the cost of exporting to the EU for UK firms (9).

The Norway model

The Norway model would involve joining the European Economic Area (EEA) alongside Norway, Iceland and Liechstenstein, and these members would have the right to veto the UK’s entry (as they did for Slovakia). The UK would still need to pay a contribution to the EU Trade through an ‘EEA Grant’ – likely to be about 75 percent of the current contribution the UK makes to the EU – without the opportunity to be represented in, to vote in, or take part in EU negotiations or decisions relating to the EU or to the trade partners of the EU. The UK would then be required to adopt a significant number of EU laws that have been adopted by the EEA members.

The Swiss model

The Swiss model would involve joining the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) through a series of bi-lateral agreements, continuing to make financial contributions to the EU. Switzerland’s current contribution to the EU is about 50 percent of the UK level. The UK would probably adopt the EU legislation voluntarily, and would gain access to the EU market if it agreed to free movement of EU goods, services and capital. The UK would lose the opportunity to be represented in, to vote in, or take part in EU negotiations or decisions relating to the EU, or to the trade partners of the EU; however, the UK could negotiate a series of trade agreements with other trade groups and nations.

The best of times, the worst of times

Ultimately, no one really knows how a Brexit will affect the wider world – or pharma in particular. Roberts says that a worst case scenario for pharma could include some or all of the following: “A short transition phase for Britain to leave the EU, sterling fluctuating at a high exchange value, fast withdrawal of R&D funding, doubling of customs duties for UK exports into Europe, fast departure of UK-based pharma companies to other countries, resourcing and funding difficulties for MHRA when it tries to recruit staff it needs to provide guidance, relocation of EMA, legal action against UK authorities for the costs of Brexit, and delays in implementing EU initiatives, such as anti-counterfeit coding on packs of medicines.”

Meanwhile, Levi raises the possibility of a drawn-out creation of a new regulatory agency to replace the EMA and a complex approvals process within the new regulatory framework that could potentially discourage companies from launching products in the UK, depending on the complexity of the process. “UK prices may also be removed from international reference pricing baskets across the EU, which could have the effect of driving down pharmaceutical prices in many markets across the continent,” he adds.

And what about the best-case scenario? Roberts describes an orderly withdrawal of Britain with the opt-outs it seeks, with no change to how it trades inward and outward products and services, with no resistance from other EU member states to Britain’s proposals.

“A best-case scenario would be one in which the UK strikes a deal to remain in the EMA or creates a straightforward regulatory agency quickly,” says Levi. “The new regulatory agency develops a streamlined approval process and loosens restrictions on research; corporate taxes are reduced significantly to encourage pharmaceutical investment; UK prices are retained in all international reference pricing baskets across the EU; and a free trade agreement eliminating all importing restrictions between the UK and the EU is negotiated.”

The vote will take place on June 23, 2016. Look out for the announcement of the results on our social media channels – and our thoughts on the future of pharma! And let’s not forget that a Brexit isn’t the only political issue that may be shaking pharma’s world in 2016. In November, the US – the largest pharmaceutical market in the world – will be holding its Presidential elections. We’ll be reporting on this – and how each candidate’s plans could affect the pharma industry – closer to the time.

If you’re hungry for more information then check out our three online exclusive articles:

- J Curtice, “How deeply does Britain’s Euroscepticism run?” NatCen Social Research Report on British Attitudes (2015). Available at: bit.ly/26zJ8lW

- F Sayers, “Polls suggest Brexit has (low) turnout on its side”, The Guardian (2016). Available at: bit.ly/1WNH2In

- The White House, “Remarks by the President Obama and Prime Minister Cameron in joint press conference” (2016). Available at: 1.usa.gov/1T47BGh

- ABPI, “Global pharmaceutical industry and market” (2016). Available at: bit.ly/23Bijth

- Nature, “Scientists say ‘no’ to UK exit from Europe in Nature poll” (2016). Available at: bit.ly/1UCHhZH

- Reuters, “Swedish industry wants European medicines agency if UK quits EU” (2016). Available at: reut.rs/1YW4sMV

- The Financial Times, “UK’s life sciences sector is ambitious for the EU,” (2016). Available at: on.ft.com/1X1xg87

- EFPIA, “EFPIA statement on Brexit,” (2016), Available at: bit.ly/1pNxl1H

- S Dhingra and T Sampson, “Life after Brexit: What are the UK’s options outside the European Union?” Centre for Economic Performance, The London School of Economics and Political Science (2016). Available at: bit.ly/1Q7sAJs

Over the course of my Biomedical Sciences degree it dawned on me that my goal of becoming a scientist didn’t quite mesh with my lack of affinity for lab work. Thinking on my decision to pursue biology rather than English at age 15 – despite an aptitude for the latter – I realized that science writing was a way to combine what I loved with what I was good at.

From there I set out to gather as much freelancing experience as I could, spending 2 years developing scientific content for International Innovation, before completing an MSc in Science Communication. After gaining invaluable experience in supporting the communications efforts of CERN and IN-PART, I joined Texere – where I am focused on producing consistently engaging, cutting-edge and innovative content for our specialist audiences around the world.