Safety First - Sizing Up Biologics Side Effects

Biologic medicines present unique challenges for pharmacovigilance. And with biosimilars hitting the market, life just got more complicated – especially when products share the same name.

It is widely acknowledged that full reporting of all adverse drug reactions (ADRs) is unlikely; however, the information that we do gather through pharmacovigilance (PV) is crucial for timely remedial action. Here, I give an overview of the unique challenges faced by PV systems when considering biologics and shed light on how a simple change in prescribing practices could help improve traceability – one of the key factors in ensuring accurate PV.

Biologics are complex to develop and manufacture, and the resulting product has a molecular structure and weight that is much larger than traditional ‘small-molecule’ products. Recent publications have also drawn attention to “non-biological complex drugs” (1), which may share some challenges with biological medicines, but these are outside of the scope of this article.

Benefit vs risk

Biologics are a mainstay in modern medicine but, as with their small-molecule counterparts, they can cause ADRs. At the end of development, a biologic’s known safety profile is based on data from clinical trials of limited duration and size; although there may also be known therapeutic class safety risks identified with functionally related biologics. As many of these products are developed for chronic administration it is important that the safety effects of the product continue to be collected in the post-authorization setting through PV. Biologics can be associated with specific ADRs, caused by a number of key factors (2).

Unique properties

Size

The large molecular size of biologics means that they can be ‘seen’ by the body’s immune system, which is in direct contrast to small-molecule products, which enter the body unnoticed. The immune response to the larger biological molecule results in the production of antidrug antibodies (immunogenicity).

Immunogenicity may have no clinically relevant impact on safety or efficacy, or it could be associated with ADRs. The severity of such immunogenicity-mediated ADRs can range from very minor; for example, swelling or redness at the injection site, to life-threatening conditions, such as pure red cell aplasia – a very rare immune reaction seen in patients administered with recombinant epoetin (3), or thrombocytopenia, which can be seen in patients administered with recombinant thrombopoietin (4). In both examples, patients develop antidrug antibodies that bind to both the recombinant protein and the body’s own endogenous supply, rendering both inactive and leading to loss of function with serious safety implications. It should be noted that such instances are rare (3,4).

Immunogenicity often occurs weeks or even months after the first administration. Therefore, it is important that PV systems are able to detect signals when they occur and accurately attribute them to the causative agent, both for the clinical benefit of the patient, and to determine if factors such as variations in manufacturing were responsible, so that preventative action can be taken (5).

Manufacturing

Biological medicinal products require complex manufacturing processes that involve many individual steps and hundreds of in-process controls (6). As the products are manufactured in living systems, the final medicines have batch-to-batch variability, are relatively unstable and, consequently, display a dynamic safety profile (6).

Manufacturing changes are also common during the lifecycle of any product and may occur for a range of reasons, including compliance with regional requirements, a new manufacturing site, or supplier changes. Such changes may affect the safety profile of the medicine – and there are notable examples in the public record of this – although in most instances there are no problems (7-9). Of course, changes are always assessed for their effect on the safety profile of the medicine and appropriate testing is conducted, but we can only know for sure that there have been no adverse effects on safety once the product is being used in practice.

Inaccurate pre-clinical models

The pre-clinical models used in standard development do not always give a good indication of how the biologic will react in a human. Biologic medicines are engineered specifically to interact with human biological targets and the effects in animal models may not directly reflect the same biology anticipated in humans. The potential consequences were demonstrated with TeGenero in 2006, when pre-clinical models failed to predict a cytokine storm when the product was administered to human volunteers (10).

And if that wasn’t enough...

In recent years there has been a fourth consideration when discussing safety of biological medicinal products: biosimilars. Biosimilars are designed to mirror a biological medicine already on the market (once the originator’s product patent has expired) (11), but because manufacturing details remain confidential even after patent expiry the biosimilar is produced via a novel manufacturing process, with the same risk of batch-to-batch variability and susceptibility to profile changes described above. In terms of PV, we need to consider biosimilars as separate products.

What’s INN a name?

Once a healthcare professional or patient becomes aware of a side effect they are responsible for reporting it to the national regulatory authority and/or the manufacturer (12,13). In a situation where there is a single product with a unique name or where two or more identical products share the same name (such as small-molecule generics), the name of the product on the report will always allow the side effect to be attributed accurately so that any necessary remedial action can be taken, such as adding new warnings in the product labeling or removing the product from the marketplace.

As an example, let’s look at the number of reports from the public information available in ADR reports in EudraVigilance for Humira® (adalimumab). As of September 2014, 28,211 events have been reported (14). Although no timeframe is given for the reporting period, if we consider that the product was first registered in 2003, we can estimate that around 2500 reports are received each year. In this case, we can be sure that all events have been ascribed accurately, as there is only a single product.

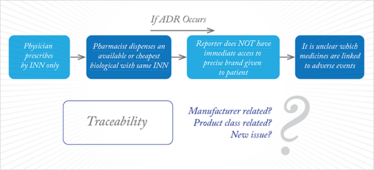

However, there is precedence for biosimilars to share the same International Non-Proprietary Name (INN) as the reference product because of their similar nature (15). Let’s consider a biosimilar version of adalimumab. The two biological medicinal products (reference product and biosimilar) could share the same INN. Now, let’s imagine that after authorization the biosimilar displays a previously unseen ADR. A PV report where only the INN is provided would not allow the side effect to be attributed to a single product, but rather to both the reference product and the biosimilar. Therefore, the signal may be misguided and could delay preventative or remedial action, which is illustrated in Figure 1 (16). However, by encouraging physicians to use the brand or trade name when prescribing biologics, the issue can easily be avoided (see Figure 2) (16).

Figure 1. ADR reporting with INN prescribing.

Figure 2. ADR reporting with brand name prescribing.

The naming issue was identified by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which issued a statement in 2008 in their Safety Update that instructed physicians to prescribe biological medicinal products by brand name (17):

“To allow us to perform product/brand-specific pharmacovigilance, when reporting a suspected ADR to a biological medicine (such as blood products, antibodies and advanced therapies [such as gene and tissue therapy]) or vaccine, in addition to the substance please ensure that you provide the brand name (or product licence number and manufacturer), and the specific batch-number, on the report.”

The European Union (EU), which has led the way in biosimilar development, recently acknowledged the unique safety profile of biosimilars in its so-called PV legislation (18, 19). The legislation, which came into effect in July 2012, specifically calls out the need for all ADRs involving biological medicinal products to be reported by trade name rather than INN. In Europe, all medicines must have a trade name that is either an invented brand name or a combination of the INN and the registered sponsor’s name (e.g., Filgrastim Hexal®), which allows safety profiles to be ascribed accurately and ensures that action can be taken on a product-by-product basis. As European Member States have been implementing this requirement, it is interesting to note that the MHRA has amended its electronic Yellow Card scheme (which is used for submitting ADRs to the agency) to request the specific brand name of the biological medicinal product. The MHRA has also been proactive in providing guidance to prescribers to provide the brand name to prevent any uncertainty when reporting ADRs (20).

A global solution?

Other regulatory authorities outside of Europe may not be able to apply the trade-name approach or may also seek a distinguishable, non-proprietary identifier for independently manufactured biologics. Bearing this in mind, the INN Expert Group recently recommended that the World Health Organization – which is responsible for issuing INNs – develop a system for assigning biological qualifiers (BQ), an alphabetic code assigned at random to a biological active substance manufactured at a specified site (21). The BQ would be used in combination with the INN to provide a unique reference for the manufacturer and the manufacturing site. This proposal continues to be discussed by the Expert Committee, but I believe that it would be of great use in terms of PV and supporting traceability. Additionally, if this system were to be adopted on a worldwide basis, it would be possible for ADRs reported for biologics to be easily communicated to all regions, enhancing global ADR signaling initiatives.

However, although the main concept is sound, industry groups, such as the International Federation of Pharmaceutical and Manufacturing Associations, are concerned by some aspects; for example, the linkage of the BQ with the manufacturing site, which could result in unnecessary BQs being generated for the same product, if it is manufactured at multiple sites. It could all get very confusing for prescribers and patients (22).

We’re likely to see more discussion ahead of a solution, but whatever path is chosen, efforts must be made to ensure that any requirements are properly understood and implemented. What is clear is that all stakeholders (prescribers, patients, the pharmaceutical industry, governments) have their part to play in ensuring that PV systems contain accurate information to ensure that safety signals are collected post-approval – and then analyzed without delay.

- D. Crommelin et al., “Different Pharmaceutical Products Need Similar Terminology”, The AAPS Journal 16, 11–14 (2014).

- T. J. Giezen et al., “Pharmacovigilance of Biopharmaceuticals – Challenges Remain”, Drug Safety 32(10), 811–817 (2009).

- C. Pollock et al., “Pure Red Cell Aplasia Induced by Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents”, Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 3, 193–199 (2003).

- J. Bryan et al., “Thrombocytopenia in Patients With Myelodysplasic Syndromes. Seminars in Hematology”, 47(3), 274-280 (2010).

- T. J. Giezen et al., “Safety-Related Regulatory Actions for Biologicals Approved in the United States and European Union”, JAMA 300(16), 1887 (2008).

- EuropaBio. Guide To Biological Medicines. A Focus On Biosimilar Medicines. www.europabio.org. Accessed 6 Aug 2014.

- European Medicines Agency. “Note For Guidance On Biotechnological/Biological Products Subject To Changes In Their Manufacturing Process. Cpmp/Ich/5721/03”. www.ema.europa.eu. Accessed on 7 Aug 2014.

- S Ramanan et al., “Drift, Evolution And Divergence In Biologics And Biosimilars Manufacturing”, BioDrugs 28(4), 363–372 (2014)

- G Grampp et al., “Managing Unexpected Events in the Manufacturing of Biological Medicines”, BioDrugs 27, 305–316 (2013).

- JG Sathish et al., “Challenges And Approaches For The Development Of Safer Immunomodulatory Biologics”, Nat. Rev. Drug. Disc. 12, 306–324 (2013).

- European Medicines Agency. “Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products (CHMP/437/04)”, www.ema.europa.eu. Accessed 11 Sept 2014.

- “Directive 2010/84/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 Amending, As Regards Pharmacovigilance, Directive 2001/83/Ec On The Community Code Relating To Medicinal Products For Human Use”, Off. J. Eur. Union 348, 74–99 (2010).

- “Regulation (EU) No 1235/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 Amending, As Regards Pharmacovigilance Of Medicinal Products For Human Use, Regulation (Ec) No 726/2004 Laying Down Community Procedures For The Authorisation And Supervision Of Medicinal Products For Human And Veterinary Use And Establishing A European Medicines Agency, And Regulation (Ec) No 1394/2007 On Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products Text With Eea Relevance”, Off. J. Eur. Union 348, 1–16 (2010).

- European Database Of Suspected Adverse Drug Reaction Reports. www.adrreports.eu. Accessed 21 Oct 2014.

- “Fight Continues Over Biosimilar Naming Standard”, 27 Sept 2013. www.gabionline.net . Accessed 10 Sept 2014.

- S. Ramanan, “Pharmacovigilance and Risk Management Plans Biosimilars (SBP’s )”, 13 May 2014

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. “Drug Safety Update”, Volume 1, Issue 7 (2008).

- “Directive 2010/84/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 Amending, As Regards Pharmacovigilance, Directive 2001/83/Ec On The Community Code Relating To Medicinal Products For Human Use”, Off. J. Eur. Union. 348, 74–99 (2010).

- “Regulation (EU) No 1235/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 amending, As Regards Pharmacovigilance Of Medicinal Products For Human Use, Regulation (Ec) No 726/2004 Laying Down Community Procedures For The Authorisation And Supervision Of Medicinal Products For Human And Veterinary Use And Establishing A European Medicines Agency, And Regulation (Ec) No 1394/2007 On Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products Text With Eea Relevance.” Off. J. Eur. Union. 348, 1–16 (2010).

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Drug Safety Update 6, 4 (2012).

- World Health Organisation. “Biological Qualifier An INN Proposal. INN Working Doc. 14.342”, www.who.int

- T. Schreitmueller, “WHO INN Working Doc. 14.342 Biological Qualifier – An INN Proposal The IFPMA Perspective”, Presented Pre-ICDRA, Workshop 3, Nomenclature Rio de Janeiro, August 24, 2014

Currently Regulatory Affairs Manager at Amgen, UK, Catherine Akers began her career as a clinical research associate, monitoring the conduct of clinical trials and visiting doctors responsible for trialling new drugs. “The collection of safety events for subjects is key in any clinical trial but that is only the tip of the iceberg,” says Catherine. “The continued collection of safety information once a medicine is in use ensures that benefits and risks can be carefully assessed throughout a product’s lifecycle.” As the safety of drugs continues to make newspaper headlines, Catherine believes that more measures to monitor the safety of medicines can only be a good thing. And that is where she is today; using her knowledge of drug development and current legislation to advocate for increasingly robust practices for the collection of safety events.